News:

Lost Treasures

Financial Times 2 December 2011

By Feargus O'Sullivan

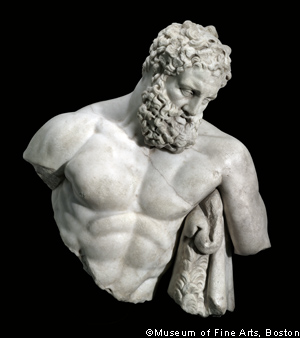

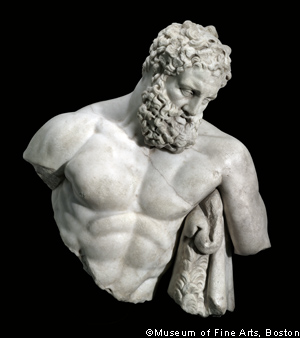

Return ticket: the torso of the Weary Herakles was sent to Turkey to be reunited with the rest of the statue

In March this year, a statue of Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of love and beauty, left the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, its home since 1988, to return to the Sicilian town of Aidone, where it was discovered.

Six months later, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts returned the Weary Herakles to Turkey, so the torso of the mythological Greek hero could be reunited with the legs and pelvis of a statue discovered near Antalya in the early 1980s.

|

Soon after, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts announced it was sending a volute krater, a Greek vase showing a Dionysiac procession, back to the site where it was unearthed in Puglia, Italy.

In a bid to combat looting and illegal borrowing, the west’s great archaeological collections have begun to shed star items at such a rate that collectors may come to remember 2011 as the year when antiquities went home.

US galleries are not alone in packing prized antiquities back into crates to return them home. Berlin’s Pergamon Museum recently returned the Hattusa Sphinx, a large Hittite statue, to Turkey. It was unearthed by German archeologists in central Turkey nearly 100 years ago, and then shipped to Berlin.

It is hard to mourn the return of the pieces. It seems all were taken from their original sites without sufficient permission. And, with the exception of the Hattusa Sphinx, all were removed after the 1970 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation convention that banned the illicit export of artefacts.

Nonetheless, to those still guarding contested treasures, such as the British Museum’s Elgin Marbles or Berlin’s Pergamon Altar, the repatriations might seem like the beginning of a worrying trend. The moves have undoubtedly highlighted the risk inherent in the antiques market, and the potential fragility of collectors’ investments.

While some critics see wealthy collectors as evil robbers, intent on denuding vulnerable historical sites by any means necessary, many antiquities enthusiasts try to collect ethically.

Yet how will they be affected by the spate of repatriations?

Dorothy King, an archaeologist who is compiling a database of looted archaeological material, believes that the big collections’ heavy toll of looted artefacts stems from a combination of lax dealers and collectors willing to accept shaky provenances. On the collectors’ side, the old provenances once claimed for the items can look implausible in hindsight.

Many collectors are quick to dismiss concerns that returns, like the Getty’s Aphrodite, represent the beginnings of a deluge of revelations about looted artefacts.

. . .

Hedge fund founder Christian Levett, who recently opened Mougins Museum of Classical Art in Provence to exhibit his antiquities collection, says: “Some writers have been suggesting that over 50 per cent of antiquities traded recently have been looted since 1970, but in my experience that number cannot possibly be true. The antiquities market has existed for 1,000 years, so to suggest that a large proportion of it has turned up in the last 40 years doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Levett also points out that the lack of clear documentation about some objects does not mean they have been stolen.

“Apart from the fact that a large number of items do have lengthy provenance, many non-looted objects genuinely don’t have a paper trail with them,” he says. “Families move houses and contents are sold; people die and details are lost.

“It’s also probable that, over a period of a great many decades, substantial amounts of pieces have been sold without leaving a paper trail intentionally by the owners, to avoid capital gains tax, to circumvent divorce settlements, to avoid other members of the family knowing that you’re selling it or to avoid attracting publicity to an offshore company.

“While I only buy objects with a clearly documented provenance, there are clearly thousands of items that have traded over the years that don’t have this and which aren’t necessarily looted.”

King also agrees that a murky source is not automatically a corrupt one. “The problem is a lot of dealers put these provenances on,” she says. “They’ll say, for example, ‘English collection, 1950’, which is very vague and difficult to verify. On the other side of the coin, it could be a real, valid case of someone simply selling on a long-held inheritance and not wanting people to know about it.”

However, even a collector like Levett acknowledges: “I have never knowingly bought any items that have passed through the hands of [dealers convicted of selling looted pieces] such as Giacomo Medici, but when I first started collecting that was down to pure luck as I’ve only read about their exploits relatively recently.

“I’d only been collecting antiquities for seven years and, by then, dealers had probably already started to veto them. And in the last three years, because everyone knew my collection was destined for public display, no one would have risked it anyway.”

Following cases like that of Medici – the Italian dealer sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2004 for selling numerous stolen artefacts – many collections are more contrite and willing to return items. The Minneapolis Institute’s volute krater, for example, was scheduled for return after a photograph of it was discovered during a raid on Medici’s gallery in the Geneva Freeport.

Such returns, however, do not always engender as much goodwill as one might expect. Kjeld von Folsach, director of the David Collection, a Copenhagen-based private Islamic art museum from which the Turkish government is seeking some items, expresses frustration at what he sees as the manipulation of his institution’s good faith.

. . .

A few years back we bought some Seljuk-era [11th-14th-century Turkish] wooden panels that we thought originated either in Turkey or northern Syria but couldn’t locate a source for,” he says. “The Turkish authorities informed us a year later that they had been stolen from a mosque in Beysehir, Turkey, and we voluntarily returned them straight away, before they had even been exhibited.

“Afterwards, they suddenly raised the number of objects they wanted returned from the David Collection from three to eight. I was very disappointed – it was as if we had whetted their appetite and they felt they could now get whatever they wanted.”

Nevertheless, von Folsach says the current pressure to send back objects with suspicious histories has brought about a cultural shift among collectors.

“When I started, most institutions of our kind looked at ourselves as guardians – as saviours of worldwide heritage wherever it originated,” he says. “When things were offered from places like war zones, we of course refused them but we did sometimes accept items without crystal-clear provenance. Those days are over.”

Yet Levett points out that the new, more stringent attitude to provenance may scupper some sales, but has also made safer parts of the market more buoyant.

“What’s happened in the last few years is that the price of antiquities with a strong provenance has shot up, while those with a weak one are not really moving,” he says. “A two-tier market of pricing has developed, and the sky is the limit for items with great provenance.”

By Feargus O'Sullivan

Return ticket: the torso of the Weary Herakles was sent to Turkey to be reunited with the rest of the statue

In March this year, a statue of Aphrodite, the ancient Greek goddess of love and beauty, left the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, its home since 1988, to return to the Sicilian town of Aidone, where it was discovered.

Six months later, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts returned the Weary Herakles to Turkey, so the torso of the mythological Greek hero could be reunited with the legs and pelvis of a statue discovered near Antalya in the early 1980s.

|

Soon after, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts announced it was sending a volute krater, a Greek vase showing a Dionysiac procession, back to the site where it was unearthed in Puglia, Italy.

In a bid to combat looting and illegal borrowing, the west’s great archaeological collections have begun to shed star items at such a rate that collectors may come to remember 2011 as the year when antiquities went home.

US galleries are not alone in packing prized antiquities back into crates to return them home. Berlin’s Pergamon Museum recently returned the Hattusa Sphinx, a large Hittite statue, to Turkey. It was unearthed by German archeologists in central Turkey nearly 100 years ago, and then shipped to Berlin.

It is hard to mourn the return of the pieces. It seems all were taken from their original sites without sufficient permission. And, with the exception of the Hattusa Sphinx, all were removed after the 1970 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation convention that banned the illicit export of artefacts.

Nonetheless, to those still guarding contested treasures, such as the British Museum’s Elgin Marbles or Berlin’s Pergamon Altar, the repatriations might seem like the beginning of a worrying trend. The moves have undoubtedly highlighted the risk inherent in the antiques market, and the potential fragility of collectors’ investments.

While some critics see wealthy collectors as evil robbers, intent on denuding vulnerable historical sites by any means necessary, many antiquities enthusiasts try to collect ethically.

Yet how will they be affected by the spate of repatriations?

Dorothy King, an archaeologist who is compiling a database of looted archaeological material, believes that the big collections’ heavy toll of looted artefacts stems from a combination of lax dealers and collectors willing to accept shaky provenances. On the collectors’ side, the old provenances once claimed for the items can look implausible in hindsight.

Many collectors are quick to dismiss concerns that returns, like the Getty’s Aphrodite, represent the beginnings of a deluge of revelations about looted artefacts.

. . .

Hedge fund founder Christian Levett, who recently opened Mougins Museum of Classical Art in Provence to exhibit his antiquities collection, says: “Some writers have been suggesting that over 50 per cent of antiquities traded recently have been looted since 1970, but in my experience that number cannot possibly be true. The antiquities market has existed for 1,000 years, so to suggest that a large proportion of it has turned up in the last 40 years doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Levett also points out that the lack of clear documentation about some objects does not mean they have been stolen.

“Apart from the fact that a large number of items do have lengthy provenance, many non-looted objects genuinely don’t have a paper trail with them,” he says. “Families move houses and contents are sold; people die and details are lost.

“It’s also probable that, over a period of a great many decades, substantial amounts of pieces have been sold without leaving a paper trail intentionally by the owners, to avoid capital gains tax, to circumvent divorce settlements, to avoid other members of the family knowing that you’re selling it or to avoid attracting publicity to an offshore company.

“While I only buy objects with a clearly documented provenance, there are clearly thousands of items that have traded over the years that don’t have this and which aren’t necessarily looted.”

King also agrees that a murky source is not automatically a corrupt one. “The problem is a lot of dealers put these provenances on,” she says. “They’ll say, for example, ‘English collection, 1950’, which is very vague and difficult to verify. On the other side of the coin, it could be a real, valid case of someone simply selling on a long-held inheritance and not wanting people to know about it.”

However, even a collector like Levett acknowledges: “I have never knowingly bought any items that have passed through the hands of [dealers convicted of selling looted pieces] such as Giacomo Medici, but when I first started collecting that was down to pure luck as I’ve only read about their exploits relatively recently.

“I’d only been collecting antiquities for seven years and, by then, dealers had probably already started to veto them. And in the last three years, because everyone knew my collection was destined for public display, no one would have risked it anyway.”

Following cases like that of Medici – the Italian dealer sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2004 for selling numerous stolen artefacts – many collections are more contrite and willing to return items. The Minneapolis Institute’s volute krater, for example, was scheduled for return after a photograph of it was discovered during a raid on Medici’s gallery in the Geneva Freeport.

Such returns, however, do not always engender as much goodwill as one might expect. Kjeld von Folsach, director of the David Collection, a Copenhagen-based private Islamic art museum from which the Turkish government is seeking some items, expresses frustration at what he sees as the manipulation of his institution’s good faith.

. . .

A few years back we bought some Seljuk-era [11th-14th-century Turkish] wooden panels that we thought originated either in Turkey or northern Syria but couldn’t locate a source for,” he says. “The Turkish authorities informed us a year later that they had been stolen from a mosque in Beysehir, Turkey, and we voluntarily returned them straight away, before they had even been exhibited.

“Afterwards, they suddenly raised the number of objects they wanted returned from the David Collection from three to eight. I was very disappointed – it was as if we had whetted their appetite and they felt they could now get whatever they wanted.”

Nevertheless, von Folsach says the current pressure to send back objects with suspicious histories has brought about a cultural shift among collectors.

“When I started, most institutions of our kind looked at ourselves as guardians – as saviours of worldwide heritage wherever it originated,” he says. “When things were offered from places like war zones, we of course refused them but we did sometimes accept items without crystal-clear provenance. Those days are over.”

Yet Levett points out that the new, more stringent attitude to provenance may scupper some sales, but has also made safer parts of the market more buoyant.

“What’s happened in the last few years is that the price of antiquities with a strong provenance has shot up, while those with a weak one are not really moving,” he says. “A two-tier market of pricing has developed, and the sky is the limit for items with great provenance.”

© website copyright Central Registry 2024