The Guardian 15 November 2013

By Philip Oltermann in Berlin

Family of Fritz Salo Glaser, who escaped deportation during Dresden bombing, had feared artworks were destroyed

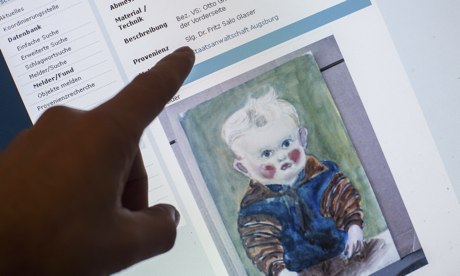

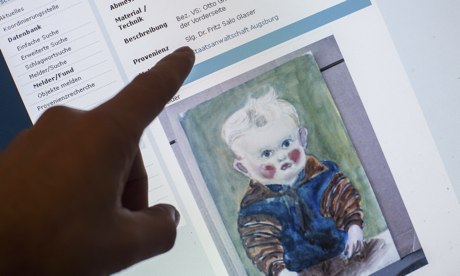

One of the works thought to have belonged to Fritz Salo Glaser on the database of works found in a Munich flat. Photograph: Action Press/Rex

Fritz Salo Glaser was to have been one of the last Jews deported from Dresden, but three days before he was due to board a train for Theresienstadt, Allied warplanes released some 4,000 tonnes on the city – and amid the confusion, Glaser was able to escape.

The firestorm razed much of the city centre, and for decades Glaser's family feared it had also consumed his cherished collection of modernist art – handpicked over the years from the studios of Dresden's most prominent artists.

This week, however, they discovered that at least some of the works had escaped the flames and survived in the Munich flat of Cornelius Gurlitt.

This week, 13 works from Glaser's collection emerged on the Lost Art internet database, where the German government is gradually uploading details about the treasure trove of artworks discovered in Gurlitt's apartment.

They include works mainly by modernist Dresden artists belonging to the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity movement, such as Bernhard Kretschmar, Otto Griebel and Conrad Felixmüller.

Glaser's daughter-in-law is still alive and living in Germany, and could lay claim to the pictures. While she herself has so far refused to be named or speak to the press, her lawyer Sabine Rudolph told the Guardian that they had been "surprised, happy, and more than a little incredulous" when they found out about the discovery.

Born in Zittau in 1876, Glaser trained as a lawyer before volunteering to fight in the first world war. In the 1920s, he distanced himself from his Jewish faith and immersed himself in Dresden's bohemian art scene while continuing to practise as a lawyer.

According to Heike Biedermann, a researcher at the Dresden state archive, Glaser was famed in the east German city for the artistic and musical salons he would hold in his house, and would often drop into artists' studios in order to trade sketches for hampers of food. "I have always known your art has eternal value," he wrote in a 1924 letter to his friend the artist Otto Dix, who painted two portraits of Glaser.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Glaser soon lost both his right to work as a lawyer and the privileges assigned to first world war veterans. Since he had given a lecture on "communism and cultural progress" in 1920, he was denounced as a communist. Unable to work, he was eventually forced to sell his art collection, and he destroyed almost all of his records for fear of further prosecution.

It remains unclear how many of his works in total eventually ended up in the hands of the collector Hildebrand Gurlitt, and passed from there to Cornelius Gurlitt's flat. The article in Focus magazine, which had originally broken the news of the discovery, mentions "dozens of works that once belonged to a Jewish collector in Dresden", most likely referring to Glaser.

The legal situation in Germany around looted art and works confiscated as "degenerate art" is highly complex. While there was a federal compensation law prescribing the return of artworks looted or sold under pressure in the immediate aftermath of the second world war, no such law is still legally binding today.

What complicates the situation further is that the former East Germany, where Dresden is situated, did not have such a law at all, but instead offered improved social security for the victims of the Nazi regime.

However, Rudolph is confident that current German civil law will allow the return of Glaser's artworks. The key question, she says, is whether Cornelius Gurlitt would try to hinder such a claim. "I am hopeful that this would not be in his interest," she said.

Over the last few days, Gurlitt has been spotted shopping in a supermarket near his flat, and on Tuesday he reportedly went to see a doctor in a taxi. Asked about the art by reporters, he said: "I can't say anything. I don't know anything."

Rudolph contacted the Bavarian customs authorities on behalf of the Glaser heir on Friday, but has yet to get a response. The 1,406 artworks are being held in a secret location outside Munich.

If the works were eventually returned to the heirs of Glaser, it would be a remarkable turn of fortune for a man double-crossed by history more than once. Denounced by the Nazis as a communist during the Third Reich, he was accused of "supporting neo-fascist endeavours" and had his "victim of fascism" status withdrawn in 1947 after successfully representing a group of former Nazi lawyers in court.

At the time, Glaser said: "If I defend these accused men it is truly not because I am a fascist or have sympathies for fascism. The fact that I am an enemy of Hitler has not extinguished my hunger for justice."

Fritz Salo Glaser was to have been one of the last Jews deported from Dresden, but three days before he was due to board a train for Theresienstadt, Allied warplanes released some 4,000 tonnes on the city – and amid the confusion, Glaser was able to escape.

The firestorm razed much of the city centre, and for decades Glaser's family feared it had also consumed his cherished collection of modernist art – handpicked over the years from the studios of Dresden's most prominent artists.

This week, however, they discovered that at least some of the works had escaped the flames and survived in the Munich flat of Cornelius Gurlitt.

This week, 13 works from Glaser's collection emerged on the Lost Art internet database, where the German government is gradually uploading details about the treasure trove of artworks discovered in Gurlitt's apartment.

They include works mainly by modernist Dresden artists belonging to the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity movement, such as Bernhard Kretschmar, Otto Griebel and Conrad Felixmüller.

Glaser's daughter-in-law is still alive and living in Germany, and could lay claim to the pictures. While she herself has so far refused to be named or speak to the press, her lawyer Sabine Rudolph told the Guardian that they had been "surprised, happy, and more than a little incredulous" when they found out about the discovery.

Born in Zittau in 1876, Glaser trained as a lawyer before volunteering to fight in the first world war. In the 1920s, he distanced himself from his Jewish faith and immersed himself in Dresden's bohemian art scene while continuing to practise as a lawyer.

According to Heike Biedermann, a researcher at the Dresden state archive, Glaser was famed in the east German city for the artistic and musical salons he would hold in his house, and would often drop into artists' studios in order to trade sketches for hampers of food. "I have always known your art has eternal value," he wrote in a 1924 letter to his friend the artist Otto Dix, who painted two portraits of Glaser.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Glaser soon lost both his right to work as a lawyer and the privileges assigned to first world war veterans. Since he had given a lecture on "communism and cultural progress" in 1920, he was denounced as a communist. Unable to work, he was eventually forced to sell his art collection, and he destroyed almost all of his records for fear of further prosecution.

It remains unclear how many of his works in total eventually ended up in the hands of the collector Hildebrand Gurlitt, and passed from there to Cornelius Gurlitt's flat. The article in Focus magazine, which had originally broken the news of the discovery, mentions "dozens of works that once belonged to a Jewish collector in Dresden", most likely referring to Glaser.

The legal situation in Germany around looted art and works confiscated as "degenerate art" is highly complex. While there was a federal compensation law prescribing the return of artworks looted or sold under pressure in the immediate aftermath of the second world war, no such law is still legally binding today.

What complicates the situation further is that the former East Germany, where Dresden is situated, did not have such a law at all, but instead offered improved social security for the victims of the Nazi regime.

However, Rudolph is confident that current German civil law will allow the return of Glaser's artworks. The key question, she says, is whether Cornelius Gurlitt would try to hinder such a claim. "I am hopeful that this would not be in his interest," she said.

Over the last few days, Gurlitt has been spotted shopping in a supermarket near his flat, and on Tuesday he reportedly went to see a doctor in a taxi. Asked about the art by reporters, he said: "I can't say anything. I don't know anything."

Rudolph contacted the Bavarian customs authorities on behalf of the Glaser heir on Friday, but has yet to get a response. The 1,406 artworks are being held in a secret location outside Munich.

If the works were eventually returned to the heirs of Glaser, it would be a remarkable turn of fortune for a man double-crossed by history more than once. Denounced by the Nazis as a communist during the Third Reich, he was accused of "supporting neo-fascist endeavours" and had his "victim of fascism" status withdrawn in 1947 after successfully representing a group of former Nazi lawyers in court.

At the time, Glaser said: "If I defend these accused men it is truly not because I am a fascist or have sympathies for fascism. The fact that I am an enemy of Hitler has not extinguished my hunger for justice."

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/13/jewish-art-collector-paintings-munich-hoard