News:

What Became of the Jewish Books?

New Yorker 1 March 2014

By Sally McGrane

In the recent film “The Monuments Men,” George Clooney and his ensemble play a fictionalized version of a group of allied officers who shot their way through Europe during World War II, rescuing big, beautiful Old Masters’ paintings and sculpture plundered by the Nazis and stored in mines and other hideouts. But what the movie doesn’t show is that, after the war, the Monuments Men also saved tons upon tons of looted books.

Starting with the infamous book burnings of May, 1933, in Berlin and university towns across Germany, books were one of the Nazis’ explicit targets. Confiscated books were considered to be as necessary to the war effort as seized munitions or fuel. “Books are essential for political and social life, the fundaments or pillars of culture,” explained Falk Wiesemann, a retired professor of German and Jewish history at the Heinrich Heine University, in Dusseldorf. “If you destroy books, you are destroying a whole culture.”

All across Europe, entire libraries of books by, about, or belonging to Jews and others of “un-German spirit,” including Freemasons, Jesuits, and Communists, were looted. Books that were valuable in some way were saved. Second and third copies of books and prayer books were pulped. What wasn’t destroyed (or stolen and reshelved in public libraries) was sent to Germany, for eventual use in a huge library planned for after the war. Meant for Nazi officers, this library would, among other things, serve to document European Jewish life before its extermination. “They wanted to prove, in their ideology, that they were right,” said F. T. Hoogewoud, a former librarian at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, in Amsterdam, when I spoke to him by phone. The library’s collection was carted off towards the end of the war. Some books, Hoogewoud added, survived as part of a “passive resistance, hidden away by non-Jewish neighbors and friends.” (In the case of the Rosenthaliana, when the Nazis came to carry away the books the librarian offered to “help,” bringing out the books so that the Germans wouldn’t access the stacks).

At the war’s end, officers for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (the “Monuments Men”) realized that, in addition to artworks, they had millions of books in their possession. In 1945, the Americans established a central collection point in Offenbach, outside Frankfurt. The largest book restitution operation in library history, the “Offenbach Archival Depot” was housed in the former headquarters of I.G. Farben, the company that had knowingly produced one of the key chemical components for the gas chambers.

The U.S. Army asked Colonel Seymour Jacob Pomrenze, an archivist who had fought in Asia and India during the war, to take charge. Pomrenze, who was born in the Ukraine (his given name was Sholom) and immigrated to Chicago with his family, in 1922, after his father was killed in a pogrom, accepted. Under challenging postwar conditions—the first winter, the building had no heating—he began dealing with the freight cars full of books, written in dozens of languages, that arrived daily from Nazi caches.

The majority of books were returned to their rightful owners. The workers at Offenbach identified them using library stamps, bookplates, and signatures they found in the books. They could also usually identify which country a library belonged to by its language. Still, many of the estimated two point five million books that passed through Offenbach could not be returned, either because the owners were dead, the libraries no longer existed, or the books’ provenance could not be identified. (Books were also not sent back to places located in the USSR.) Homeless collections were generally sent to Jewish institutions in the U.S. or Israel.

One of the Offenbach books ended up at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York. Printed in St. Petersburg in 1887, it is a cultural, social, and political history of the Jewish people in Russia. When Melanie Meyer, a special collections librarian at the Center for Jewish History in New York, saw the book, it became one of her favorites. It had not one but four different stamps showing ownership. “I’d never seen that before,” she said. These stamps told the story of how the book had travelled across Europe to the United States: from St. Petersburg, it was probably donated to the original YIVO in Vilna; the Nazis, who levelled the library there, seized the book, which made its way to Offenbach after the war, before coming to the U.S.

Meyers decided to launch an online exhibit, timed to coincide with the Clooney movie, highlighting the Monuments Men’s work with books. Using a scrapbook with photos of some three thousand stamps indicating the ownership of books that passed through Offenbach, Meyers and her co-curator, David Rosenberg, matched the stamps with the libraries they came from. On a map of Europe posted on the exhibit’s website, you can click on, say, Perm, and a stamp pops up, along with information about the Perm Branch of the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia.

The exhibit—which shows the sheer geographical scope of Nazi looting—is a kind of virtual recreation of libraries that once existed. “When you look at the stamps, you can tell something about the library,” said Rosenberg. “I love how some stamps are very businesslike, while others are very beautiful, with different motifs. It says something about the owners, what was important to them.” “We found book stamps from places you wouldn’t have thought people were reading,” Rosenberg added.

For now, they’re putting up ten new library stamps a week, said Meyers. Next, they will start posting stamps that show that a book belonged to a family. “Online, people can help identify [the stamps],” said Meyers. “Right now, sometimes all we know is that it came from Germany.”

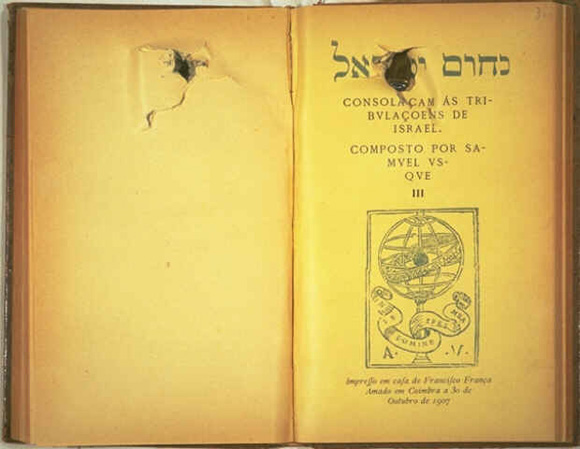

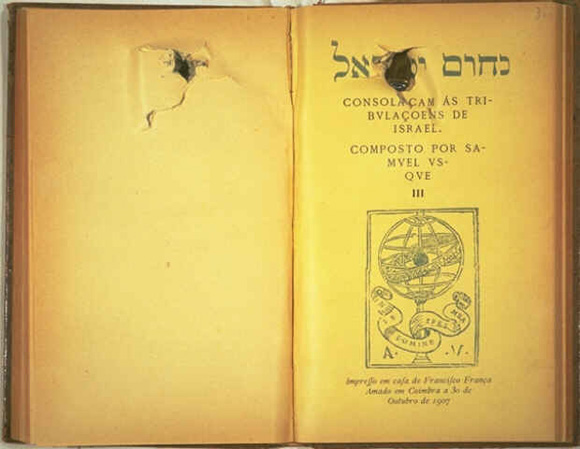

Emile Schrijver, the current curator of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana—whose collection was successfully returned to Amsterdam, via Offenbach, after the war—said that it can be very difficult to ascertain the true history of a particular book. For example, one of the Rosenthaliana books, a history of the suffering of the Jewish people, came back with a bullet through its cover. For years, the library told visitors that the bullet was German. Then a ballistics expert informed them that the bullet was American. (Packed in a hundred and fifty crates, the Rosenthaliana’s collection had been hidden in a shed at a castle outside Frankfurt; as it turned out, American soldiers, on entering large, dark spaces like that one, would often shoot to see if anyone was there).

“This is a black page in the history of the Jewish book,” said Schrijver, of the devastation wrought by the Nazis. “There are other black pages. But there are beautifully illuminated pages, too. They didn’t destroy it.”

Sally McGrane is a journalist based in Berlin.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2014/03/what-became-of-the-jewish-books.html

By Sally McGrane

In the recent film “The Monuments Men,” George Clooney and his ensemble play a fictionalized version of a group of allied officers who shot their way through Europe during World War II, rescuing big, beautiful Old Masters’ paintings and sculpture plundered by the Nazis and stored in mines and other hideouts. But what the movie doesn’t show is that, after the war, the Monuments Men also saved tons upon tons of looted books.

Starting with the infamous book burnings of May, 1933, in Berlin and university towns across Germany, books were one of the Nazis’ explicit targets. Confiscated books were considered to be as necessary to the war effort as seized munitions or fuel. “Books are essential for political and social life, the fundaments or pillars of culture,” explained Falk Wiesemann, a retired professor of German and Jewish history at the Heinrich Heine University, in Dusseldorf. “If you destroy books, you are destroying a whole culture.”

All across Europe, entire libraries of books by, about, or belonging to Jews and others of “un-German spirit,” including Freemasons, Jesuits, and Communists, were looted. Books that were valuable in some way were saved. Second and third copies of books and prayer books were pulped. What wasn’t destroyed (or stolen and reshelved in public libraries) was sent to Germany, for eventual use in a huge library planned for after the war. Meant for Nazi officers, this library would, among other things, serve to document European Jewish life before its extermination. “They wanted to prove, in their ideology, that they were right,” said F. T. Hoogewoud, a former librarian at the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, in Amsterdam, when I spoke to him by phone. The library’s collection was carted off towards the end of the war. Some books, Hoogewoud added, survived as part of a “passive resistance, hidden away by non-Jewish neighbors and friends.” (In the case of the Rosenthaliana, when the Nazis came to carry away the books the librarian offered to “help,” bringing out the books so that the Germans wouldn’t access the stacks).

At the war’s end, officers for the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (the “Monuments Men”) realized that, in addition to artworks, they had millions of books in their possession. In 1945, the Americans established a central collection point in Offenbach, outside Frankfurt. The largest book restitution operation in library history, the “Offenbach Archival Depot” was housed in the former headquarters of I.G. Farben, the company that had knowingly produced one of the key chemical components for the gas chambers.

The U.S. Army asked Colonel Seymour Jacob Pomrenze, an archivist who had fought in Asia and India during the war, to take charge. Pomrenze, who was born in the Ukraine (his given name was Sholom) and immigrated to Chicago with his family, in 1922, after his father was killed in a pogrom, accepted. Under challenging postwar conditions—the first winter, the building had no heating—he began dealing with the freight cars full of books, written in dozens of languages, that arrived daily from Nazi caches.

The majority of books were returned to their rightful owners. The workers at Offenbach identified them using library stamps, bookplates, and signatures they found in the books. They could also usually identify which country a library belonged to by its language. Still, many of the estimated two point five million books that passed through Offenbach could not be returned, either because the owners were dead, the libraries no longer existed, or the books’ provenance could not be identified. (Books were also not sent back to places located in the USSR.) Homeless collections were generally sent to Jewish institutions in the U.S. or Israel.

One of the Offenbach books ended up at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York. Printed in St. Petersburg in 1887, it is a cultural, social, and political history of the Jewish people in Russia. When Melanie Meyer, a special collections librarian at the Center for Jewish History in New York, saw the book, it became one of her favorites. It had not one but four different stamps showing ownership. “I’d never seen that before,” she said. These stamps told the story of how the book had travelled across Europe to the United States: from St. Petersburg, it was probably donated to the original YIVO in Vilna; the Nazis, who levelled the library there, seized the book, which made its way to Offenbach after the war, before coming to the U.S.

Meyers decided to launch an online exhibit, timed to coincide with the Clooney movie, highlighting the Monuments Men’s work with books. Using a scrapbook with photos of some three thousand stamps indicating the ownership of books that passed through Offenbach, Meyers and her co-curator, David Rosenberg, matched the stamps with the libraries they came from. On a map of Europe posted on the exhibit’s website, you can click on, say, Perm, and a stamp pops up, along with information about the Perm Branch of the Society for the Promotion of Culture among the Jews of Russia.

The exhibit—which shows the sheer geographical scope of Nazi looting—is a kind of virtual recreation of libraries that once existed. “When you look at the stamps, you can tell something about the library,” said Rosenberg. “I love how some stamps are very businesslike, while others are very beautiful, with different motifs. It says something about the owners, what was important to them.” “We found book stamps from places you wouldn’t have thought people were reading,” Rosenberg added.

For now, they’re putting up ten new library stamps a week, said Meyers. Next, they will start posting stamps that show that a book belonged to a family. “Online, people can help identify [the stamps],” said Meyers. “Right now, sometimes all we know is that it came from Germany.”

Emile Schrijver, the current curator of the Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana—whose collection was successfully returned to Amsterdam, via Offenbach, after the war—said that it can be very difficult to ascertain the true history of a particular book. For example, one of the Rosenthaliana books, a history of the suffering of the Jewish people, came back with a bullet through its cover. For years, the library told visitors that the bullet was German. Then a ballistics expert informed them that the bullet was American. (Packed in a hundred and fifty crates, the Rosenthaliana’s collection had been hidden in a shed at a castle outside Frankfurt; as it turned out, American soldiers, on entering large, dark spaces like that one, would often shoot to see if anyone was there).

“This is a black page in the history of the Jewish book,” said Schrijver, of the devastation wrought by the Nazis. “There are other black pages. But there are beautifully illuminated pages, too. They didn’t destroy it.”

Sally McGrane is a journalist based in Berlin.

http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/books/2014/03/what-became-of-the-jewish-books.html

© website copyright Central Registry 2024