News:

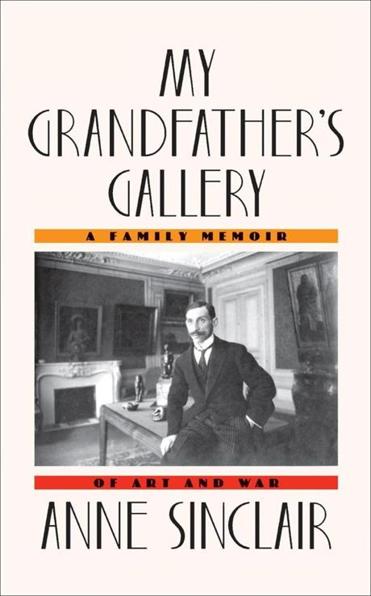

‘My Grandfather’s Gallery’ by Anne Sinclair

By Judy Bolton-Fasman

Journalist Anne Sinclair’s story tells of her grandfather’s close friendship with Picasso.

In the epilogue of “My Grandfather’s Gallery,” French political journalist Anne Sinclair writes that her slim book began as an homage to her grandfather, the influential art dealer Paul Rosenberg, rather than a biography. In a “series of impressionistic strokes,” Sinclair wanted to evoke “a man who was a stranger to me yesterday, yet who today seems quite familiar.” But Sinclair’s evocation feels more cubist than impressionist. She tells the story of her grandfather’s life thematically, reassembling it from several vantage points. And in telling that tale she also recounts her own discovery of a part of her heritage she previously had chosen to ignore.

Sinclair begins her book with a disorienting encounter with a French bureaucrat. As she attempts to establish her French citizenship for an identity card, the clerk asks Sinclair — who is Jewish — if her four grandparents are French. “ ‘[T]he last time people of their generation were asked this kind of question was before they were put on a train to Pithiviers or Beaune-la-Rolande!’ I say, my voice choking with rage, as I name the French camps where Jews were locked up by the French collaborating police before being deported by the Nazis to the death camps.”

Although the Holocaust looms over Paul Rosenberg’s story, its horrific consequences for France’s Jews and her family rarely approach Sinclair’s initial outrage on the page. This will not be the sole jarring bit in this book, however, as Sinclair’s narrative at times leaps back and forth in subject and time in slapdash fashion.

Sinclair, the former wife of Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who resigned as International Monetary Fund chief after sexual assault allegations, explains early on that for years she had little interest in hearing of her grandfather’s life. Then after turning 60 she inherited a trove of family papers — “artifacts from the realm of the unspoken, tucked away at the back of a chest of drawers.” After examining them it became apparent to the veteran journalist they contained the material of a great story.

Before the war, Rosenberg was the preeminent art dealer in Paris. He took over his father’s gallery in 1905 with his brother Léonce and then struck out on his own in 1910. His gallery at the famed 21, rue La Boétie, was home to Braque, Leger, Picasso, and other modernists whose works he displayed on the ground floor while showcasing more established painters and sculptors like Degas, Renoir, and Rodin on the mezzanine.

Author: Anne Sinclair, Translated, from the French, by Shaun Whiteside

Publisher: Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Number of pages: 240 pp.

Book price: $26

Rosenberg sold 19th century painters to support the contemporary painters in his stable, many of whom signed exclusive deals with him. Picasso came on board in 1918. The first Picasso exhibition was held at Rosenberg’s gallery in the autumn of 1919. At that time, Rosenberg also convinced Picasso to move next door to him at 23 rue La Boétie. Picasso and his first wife Olga occupied two floors. “The two men,” writes Sinclair, “became intimate in the manner of brothers — inseparable.”

Between 1918 and 1932 all of Picasso’s major works “passed through Paul’s hands.” Sinclair writes that, “If Picasso’s painting took off in the 1920s, it did so not least because Paul knew how to promote the painter and guide him in directions other than cubism.” By the time World War II began, the men had drifted apart. Picasso became involved with the surrealists and was spending more time away from Paris with his new lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, who would become a model and muse.

In June of 1940 France fell to the Germans, and the Rosenbergs fled to Floirac near Bordeaux. Rosenberg rented a vault to keep 162 of his paintings safe — among them was a self-portrait by van Gogh and paintings by Cezanne, Delacroix, Matisse, and Picasso. By September the family went into exile in New York leaving behind the paintings. The Nazis looted the vault a year later. In all, the Germans would steal 400 paintings from Rosenberg. After the war, he recovered most of them to establish his New York gallery.

“My Grandfather’s Gallery” tells Paul Rosenberg’s story in bits and pieces that construct a life and a legend through association rather than chronology. The book is also a detailed and important record of 20th century art. Yet at times it reads less like a compelling panorama and more like a plodding journey.

Judy Bolton-Fasman, a columnist for the Jewish Advocate, can be reached at www.thejudychronicles.com.