News:

One of the world’s most respected curators vanished from the art world. Now she wants to tell her story.

By Geoff Edgers

Marion True in Newburyport, Mass., where she grew up and her mother still lives. The former curator of antiquities for the J. Paul Getty Museum was indicted in 2005 by an Italian court for being part of a stolen-art ring. All charges were eventually dismissed, but her career was ruined. (Michele McDonald/for The Washington Post)

The reporters staked her out. The investigators said she conspired with crooked dealers. And her museum colleagues seemed content to watch her disappear, as if one of the world’s most powerful, respected and sought-after art historians deserved to be the only American curator brought to trial.

Ten years ago, Marion True, then curator of antiquities for the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles — the wealthiest museum in the world — was formally accused by the Italian government of taking part in a stolen-art ring. Within months, she would lose her job, her career and leave the country. Once a curator so coveted she turned down a plum offer from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, True vanished so completely that one former boss, Barry Munitz, admitted in an interview this summer that he had no idea “where she is or what she’s doing.”

J. Michael Padgett, the Princeton University Museum of Art’s curator of ancient art, spoke of her in the past tense when approached recently at a dinner toasting, of all people, the late dealer, Robert Hecht, who was brought to trial with True.

“She was a symbol,” he said. “And she died for others.”

Except that Marion True is very much alive and now, for the first time in years, has agreed to talk about her professional exile. What’s more, True has roughed out several hundred pages of a potential memoir, a draft of which she shared with The Washington Post.

A decade after her downfall, True knows that she was singled out, with Hecht, by the Italians to strike fear in American museums. The strategy worked. The Getty and others, fearing prosecution, returned hundreds of objects worth millions of dollars.

True was never found guilty — the trial ended in 2010 without a judgment — and the curator maintains her innocence. But today, for the first time, she is talking openly about the way she and her museum-world colleagues operated. Yes, she did recommend the Getty acquire works she knew had to have been looted. That statement, though, comes with a qualifier:

If she found out where a work had been dug up from, she pushed for its return. In contrast, many of her colleagues did little, if anything, to research a work’s source. None of them were put on trial.

The pursuit of True was aided by raids of dealers and a massive leak of internal Getty documents to a pair of Los Angeles Times reporters. That paper trail linked looted sites in Italy to the museum’s Malibu galleries.

Now-retired Italian prosecutor Paolo Ferri, reached recently, admits that he never imagined True going to jail.

“She was on trial for one reason,” he said. “To show an example of what Italy could do.”

Marion True leaves the Rome courthouse in November 2005 during her trial on charges of knowingly acquiring lost antiquities for the Getty. (Andreas Solaro/Agence France-Press/Getty Images)

‘A shock to the system’

In her unpublished memoir, True charts her rise from working-class Newburyport, Mass., into the mysterious, swashbuckling universe of ancient art and, finally, into an Italian courtroom. She offers a rare glimpse into the often too-cozy-for-comfort relationships among museums, dealers and collectors. She describes the absurdity of being targeted. Because even True’s detractors knew about her efforts to create collecting standards in a profession that, for decades, operated with the ethical compass of a junk bond trader on 1980s Wall Street.

True’s trial, covered with great fanfare at its start, fizzled out quietly.

“I understand why the Italians did what they did,” True, 66, said in one of a series of interviews in Newburyport, where she maintains a modest, third-floor walkup so she can visit her 91-year-old mother. “It was very clever, and it was very mean, but at least I understand why. What I never understood is why American museums did what they did. And my colleagues and my bosses never, ever stood up for me. They acted as if I had done all this stuff on my own, which would have been impossible to do. They just vanished.”

Former Getty director John Walsh, reached this summer, said that he gave a deposition explaining why True, as a curator, should not have been held responsible for Getty acquisitions. Those purchases were made by the museum’s administrators and board. But his private defense offered little solace to True. As she notes, the Getty did little to support her publicly.

“I don’t think anybody stuck their neck out,” said Max Anderson, the director of the Dallas Museum of Art. “Her indictment was a shock to the system. Everybody was watching with concern for their own fate. I don’t think it was the finest hour of the profession.”

It is late one morning, and True has heard about the book-release party, at a Turkish restaurant in New York, to celebrate the publication of Hecht’s memoir. He was the brash, legendary figure who fashioned himself a “buccaneer” during decades of selling ancient art to museums, even when he had reason to believe the works had been looted.

American art dealer Robert Hecht, who was tried along with True, leaves a Rome court in 2006. (Alessandra Tarantino/Associated Press)

She is trying to process the idea that the man charged with conspiring with her would now be celebrated over red wine, kebabs and calamari by the aging circle of curators she once called colleagues.

“Even Bob Hecht comes out of it with his book published,” True said.

In person, True is warm, funny and capable of chatting about everything from the Beatles to the proper way to grow a peony. She lives mainly in France now with her French husband, a retired architecture scholar. Her tone shifts when talk turns to the Getty. Unprintable words fly. Tears well up.

The Getty Villa in Malibu was built by John Paul Getty to re-create a first-century Roman villa. It opened to the public in 2006 after a $275 million renovation. The original was buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79. (Gabriel Bouys/AFP/Getty Images)

The Getty Villa, with its sprawling gardens, outdoor theater and galleries overlooking the Pacific Ocean in Malibu, was designed to re-create the feel of a 1st-century Roman home. The renovation of the Villa was her life’s work, an eight-year, $275 million project opened to the public in 2006. It is the main reason True turned down the Met when it offered her its top antiquities job.

True literally wrote the book on the Villa, a hardcover available for $39.95 in the museum gift shop. Her forced resignation in October 2005 came in the midst of the antiquities case but was technically for an ethical breach she admits she regrets, borrowing money (at 8.5 percent interest) for a second home from prominent museum donors Larry and Barbara Fleischman.

“I was a very happy person,” she says, looking down and beginning to cry. “I think I was good at what I did. I loved what I did. But when you know that you can’t do it anymore, then it’s over.”

So is it a good time to write a book? Even her closest friends wonder.

“It’s not like there’s something still active,” said Karen Manchester, curator of ancient art at the Art Institute of Chicago.

But then she talks about True’s influence, how she mentored Manchester, a junior curator at the Getty in the 1980s, on how to dress professionally and the proper way to carry herself around deep-pocketed collectors. She viewed True as a leader in the 1990s, testifying in Washington and speaking regularly at museum conferences about the need for stricter collection practices. That work sometimes angered colleagues at other museums.

“I’ve always wished and always thought of her as the phoenix who rises from the ashes,” Manchester said. “That there would be a role for her as a grand voice for the field. She has so much to give.”

Vartan Gregorian, the former Brown University president who now serves as president of the Carnegie Corp. of New York, believes a book would give True something she never got in a courtroom: A chance to properly defend herself.

“I told her, ‘If you don’t write your own history, others are going to write it,’ ” said Gregorian, who is also a former Getty trustee.

As of now, much of True’s story has been ceded to former Los Angeles Times reporters Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino. The pair relied on interviews and documents leaked from the Getty for their 2011 book, “Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum.” While no longer at the newspaper, Felch maintains a Web site for the book. In 2011, after reviewers argued that they had treated True too harshly, the authors posted a retort, noting that seven in 10 readers on their site “think she was guilty of trafficking in looted antiquities.”

This summer, True offered what, for the first time, is something close to a confession. No, she insists she did not conspire as part of an illicit trafficking ring, as the Italians alleged. But she did acquire art for the Getty that she knew had been stolen. How couldn’t she? It was everywhere.

A gold wreath from the 4th century B.C. was returned to Greece as a result of the True case. True says whenever a piece’s true ownership could be ascertained, the Getty would return it (Giorgos Nisiotis/Associated Press)

“The art is on the market,” True said, describing the Getty’s collecting approach. “We don’t know where it comes from. And until we know where it comes from, it’s better off in a museum collection. And when we know where it comes from, we will give it back.”

This final line, she said, is important. Other curators worried little about where a sculpture or painting came from as they competed to acquire it. But True said that whenever she discovered the source of a looted work, where it came from, the Getty returned it. That wasn’t the case with two of the most prominent museum collectors of her era, men she studied under, Cornelius Vermeule at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Met’s Dietrich von Bothmer.

Bothmer pushed the Met to purchase a 6th-century B.C. vase for $1 million in 1972 even though, True said, he once told her about the Etruscan tomb it had been stolen from. Confronted with this, the museum had to send the “Euphronios krater” back to Italy in 2006. Vermeule once acquired the top section of a Greek statue, known as the “Weary Herakles,” despite the fact that the bottom half was on display in a Turkish museum. Yet Vermeule insisted publicly in the 1990s that he had no way of knowing that the two halves, so obviously connected, were once joined. In 2011, three years after his death, the MFA returned its half to Turkey. Bothmer has also died, and never admitted publicly to buying looted art.

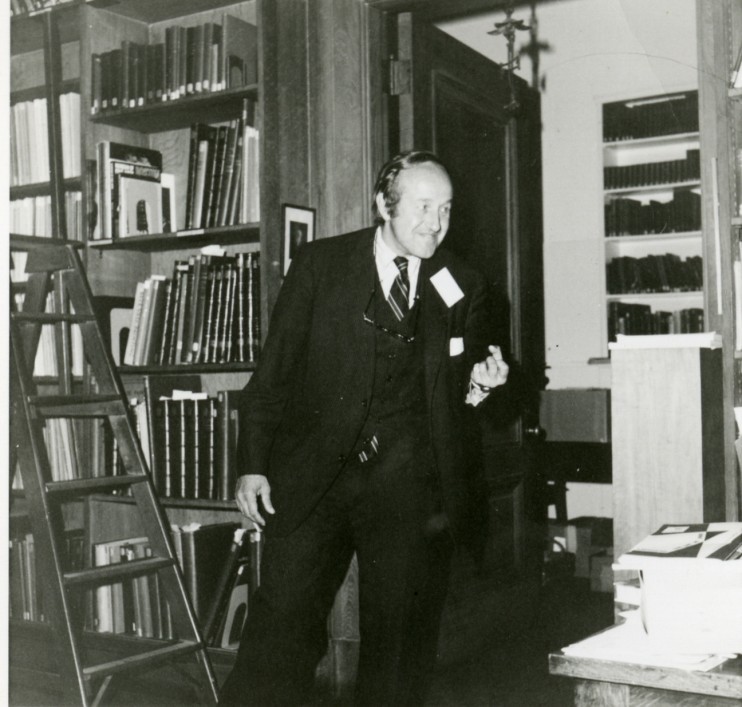

Cornelius Vermeule in 1972 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He claimed ignorance when he acquired the top half of the statue “Weary Herakles” when the bottom half was on exhibit in a Turkish museum. (Courtesy of Marion True/Courtesy Marion True)

The “Euphronios krater,” a 2,500-year-old Greek vase on the display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was returned to Italy in 2006. Curator Dietrich von Bothmer bought it from Robert Hecht, later True’s co-defendant. (Mary Altaffer/Associated Press)

The curators were both close to Hecht, who sold the “Euphronios krater” to the Met. And it was only natural that Hecht, who met True through Vermeule in the early 1970s, would count the rich Getty as one of his best clients.

Ferri, the retired Italian prosecutor, said he believed Vermeule and Bothmer — as well as former Getty directors John Walsh and Deborah Gribbon — were just as deserving as True of being prosecuted. But the information he had on True, he said, was fresher.

True arrived at the Getty as a curatorial assistant in 1982, a day remembered down to her first-day clothes (“my best French suit and a striped silk blouse”) and starting salary, $14,500. There, she encountered Jiri Frel, a former Met curator who built the Getty’s collection during the 1970s.

The Getty did not have the history of the Met or MFA. What it had was money.

Founded by American industrialist John Paul Getty, the original Villa opened in 1974. Getty never saw it. He died in 1976 while in England, leaving the museum $1.2 billion.

Even with that money available, Frel operated like a bookie during Super Bowl weekend.

“A complete rule breaker,” said Sally Hibbard, the Getty’s registrar for decades until her retirement in 2014. “He would sneak things into the museum at night, when I wasn’t there. He came from the Soviet bloc, and that was just a way of life for him.”

Frel lured donors by inflating estimated values of artworks to benefit their tax filings. He forged documents to create fake histories for purchased works. Forced out in 1984, Frel left behind works that, two decades later, would end up on Ferri’s list of demands. That mess would be left for his successor, Marion True.

On a cold night last winter, a vestige of this generation of curators gathered at a Turkish restaurant to toast Hecht.

The collector died in 2012 at the age of 92. His wife, Elizabeth, had recruited coin collector and Corning Glass family member Arthur Houghton, who served as a curator at the Getty in the 1980s, to write a lengthy foreword to a self-published memoir. The hardcover itself is a skimpy read, not even 70 pages. Hecht, who had been banned from multiple countries in the past for his dealings, offered an open letter meant to forward his main argument about antiquities. He did not traffic in stolen works. He “rescued” art by steering it to great museums.

True knew most of the minglers: Jasper Gaunt, the curator of ancient art at Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum; former Cleveland Museum of Art curator Arielle Kozloff; Princeton’s Padgett.

Houghton stood in the front of the room, toasting the known dealer in stolen works. In his foreword, Houghton described Hecht as “an adventurer, a buccaneer” whose life was “a series of capers, of quick-witted moves to buy and sell ancient art” by those who “knew how to evade the long arm of authority.”

“I have to be quite honest,” True said later about the gathering. “I would have loved to go because I think it would have shocked them.”

Marion True in Newburyport, away from museums and art-crowd parties. (Michele McDonald/For The Washington Post)

But she avoided the party, just as she avoids the classical sections of art museums. And as she considers her life in France, of gardening, cooking, family and cats, she begins to wonder whether her memoir might be one more thing to let go.

Last fall, True had been leaning toward whipping the manuscript into shape for a publisher. This summer, she has been pulling back.

“I felt I really had to put it down, from my perspective, as a kind of catharsis,” she said. “But I’ve been wavering. Do I really want to publish a book and turn my life upside down? I just don’t know that it’s worth it. I don’t know.”