News:

The scandalous, scarcely believable journey of the little Kandinsky

By Imogen Savage

Stolen twice. Re-sold around the world. The dramatic afterlife of a master’s postcard-sized painting

Housed in a 19th-century listed mansion that stretches skyward into spires, the Grisebach auction house gives off the disquieting charm of a German fairytale castle. Outside runs Fasanenstrasse, a leafy street of galleries and skincare boutiques in one of Berlin’s chicest corners. On December 1 2022, Marcin Król, the Polish consul in Berlin, climbed the steps to the building for the evening sale beginning at 6pm. A number of impressive modern artworks were on offer, including a sought-after self-portrait in oil by Max Beckmann. But it was Lot No 31, “Untitled”, a little pink Wassily Kandinsky watercolour from 1928, that had Król’s attention that evening.

Król was not at Grisebach as a buyer. Earlier that day he had sent the auction house a message demanding it stop the sale of the Kandinsky. In the hours since, representatives at Grisebach had reviewed the legal status of the artwork and its right to be sold by Inga Maren Otto, a German billionaire and philanthropist. Their decision was clear. They would proceed.

At 4.40pm, Król took to Twitter, quoting the message he’d sent to Grisebach. “Withdraw[ing] the painting from the auction,” he wrote, “[was] the only correct and moral action in this situation . . . The provenance/history of the painting stated [in the catalogue] is clear . . . the painting has ownership markings indicating its origin from the National Museum in Warsaw. [It has been registered] from the Polish side in Interpol’s database of stolen works of art.” He finished the thread with an update: “The auction house has not yet stopped selling the work. As of 4.50pm.”

Król watched on a TV screen in the corner of an anteroom as the auction began. Lot No 31 eventually appeared on the screen. Flattened by the glowing pixels, the original aqueous colours took on neon tones. There was a faint scribble underneath in Kandinsky’s handwriting. After a flurry of bids, more than doubling the upper reserve price, the hammer came down.

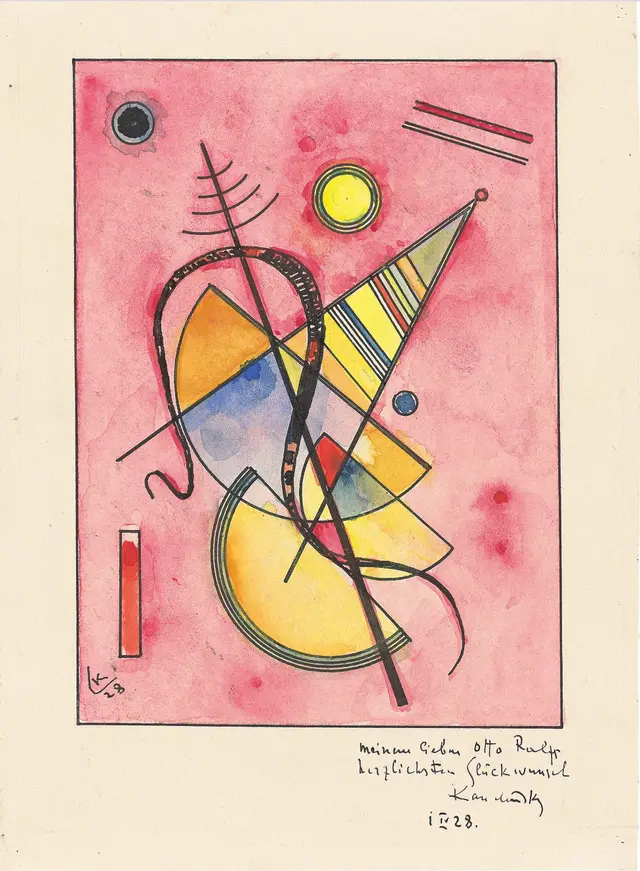

Untitled’, 1928, by Wassily Kandinsky

Afterwards, Król posted a photo to Twitter with a solemn summary of what he had witnessed. It read like both the beginning and the end of an art-crime story: “Grisebach sold Kandinsky’s watercolour [“Untitled”] for €310,000. The painting was stolen in 1984 from the National Museum in Warsaw.” Then the Berlin police showed up at the auction house, in response to a report of a stolen artwork being sold on the premises. Król’s message that day was, said Grisebach in a statement issued after the event, the first they’d learnt of the theft.

I heard about the auction of the Kandinsky watercolour some weeks later. I was intrigued by this little work on paper, the size of which is hard to gauge when viewed online. A cluster of geometric shapes and coloured washes not much bigger than a postcard, it’s not a famous piece and was never supposed to be. The personalised dedication at the bottom provides a clue as to its original, more intimate context.

Through Król’s media offensive, I began to imagine the painting in its previous lives. A valued artwork can do this; move through history like a time traveller who has seen it all, changing hands, changing walls, changing in value, picking up a few marks and scuffs, but remaining, on the surface, itself. It’s easy to forget that many of the works of art we see today have somehow weathered revolutions, wars and genocide. During and after the second world war, art collections dispersed like breadcrumbs in the mouths of sparrows. Since that time, art dealers and auction houses have continued to sell these works, right up to the present day, with values soaring.

As I began to trace the Kandinsky’s journey, I discovered the story had deeper roots than even Król had imagined. The watercolour wasn’t stolen once but twice. Having survived the Nazi party’s confiscations of modern art in the 1930s, it languished in a depot in occupied Poland before travelling back and forth across the world via private and public sales as the lines between black market and art market blurred postwar. As the trail grew more convoluted, my questions multiplied. How was it possible, I wondered, that a piece of art that we know was once stolen from a major European museum could now be sold, perfectly legally, by an important German auction house? And who, in the chain of ownership spanning nearly a century, is the rightful owner of Lot No 31?

In his Dessau studio in 1928, Wassily Kandinsky sat before a small sheet of thick paper. He drew in ink, a balance of precisely placed interlocking semicircles, triangles and floating circles, with a more irregular snakelike mark through the centre. Then he dragged his paintbrush across some watercolour pans, applying the colours to the interior of the shapes in blues, yellows and reds, and washing the surround in pink. The watery paint pooled in different areas, variegating the intensity of the colour where it settled. Then it dried, locking the painting into position. At the bottom, in pencil, the artist wrote: “Meinem lieben Otto Ralfs, herzlichsten Glückwunsch, Kandinsky I IV 28” [“To my dear Otto Ralfs, Happy Birthday, Kandinsky, 1 April 28”]. It was a gift, made for his friend and patron on the occasion of his 36th birthday.

Kandinsky’s studio was in a row of identical semi-detached houses located in a pine forest at the edge of town, where artist-professors lived and worked. This was the vision of Walter Gropius, founder of the influential modernist art and design school the Bauhaus, who designed the Dessau “Masters’ Houses” in 1925 to fit his concept of gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork. Kandinsky lived at No 6, next door to the Swiss-German artist Paul Klee. The day I visited earlier this summer, the sunny weather was heating the pines, filling the air with the same calm, sweet smell that Kandinsky, then in his late fifties, and the younger Klee would have breathed as they sat drinking tea together in the garden.

Inside, the thick, shiny paint was fresh from recent restoration work, distracting the senses from conjuring their presence. The artists’ studios, the largest rooms in their carefully designed houses, shared a wall. From the front, an enormous horizontal window frames the central focus of the house, the parallel studios in which they worked, taught and held salons: Kandinsky on the left, Klee on the right.

Otto Ralfs and his wife Käte bought their first works by Klee when they visited the Bauhaus in Weimar in September 1923. After that, their lives changed completely. The couple didn’t have a lot of money. He worked as an insurance salesman and owned a shop in his hometown, Braunschweig, in northern Germany. She was a paediatric nurse. But they were among the first people to see the value in the art being produced at the Bauhaus. At one point, they had the largest collection of Klees, and the second-largest collection of Kandinskys after Solomon R Guggenheim.

The Ralfses met Kandinsky not long after he arrived from Russia and was living in the attic apartment of another family, with his second wife, Nina Andreevskaya. “They had just three cups, and the vodka was going around in a water glass,” said Käte Ralfs, in an unpublished interview with the art historian Peg Weiss in the 1980s. Otto and Kandinsky agreed on an exchange: Ralfs would send him glasses and pots from his household-goods shop, and Kandinsky would send him artworks. The Ralfses’ collection kept growing. Later, the German artist Kurt Schwitters wrote them a letter: “I hear you are trading art for pots. My wife urgently needs a few . . . ”

“They were the typical modern Weimar-era couple,” said Nina Zimmer, great-grandniece of Käte and Otto and director of the Klee Museum, in Bern. “They had great parties and they used to swap clothes. Käte would wear a suit and Otto a dress and stockings.” Rudolf Zwirner, the German art dealer, remembers this too. “Ralfs always invited people to his modest apartment in Braunschweig’s Schuntersiedlung on Sundays to show his works on paper . . . [He] received people in women’s clothing, but no one took offence. For me it was the first encounter with a transvestite,” he wrote in a 2019 autobiography.

By 1931, the German economy was in crisis and Otto Ralfs was broke, forcing him to sell a few pieces from his collection. Provenance data shows clearly that any works leaving the Ralfs collection legally did so at around this time. Two years later, Otto and Käte looked on as Adolf Hitler stood in front of a large National Socialist demonstration outside the front of the Braunschweig Palace. Before long, the Nazis were confiscating tens of thousands of modern works of art that they considered “degenerate”, among them works by Kandinsky and Klee. Both artists left Germany when the Bauhaus was closed in 1933. The Ralfses were not immediately targeted but had started to look for a safe storage location for their collection. But in their dining room, they left three large Kandinskys hanging, including the important 1910 painting “Composition I”. They only moved them down into their air-raid shelter after the second world war began.

Otto Ralfs spent the war as a lieutenant stationed in Katowice, part of occupied Poland, but for most of his time headed a maintenance unit near the Eastern Front. When he returned on leave to Braunschweig, he and Käte packed up the largest part of their collection into five heavy boxes and organised its transportation to a depot in Katowice. In October 1944, she was visiting him in Katowice when Britain carried out “Operation Hurricane” on Braunschweig, a devastating air raid that destroyed 90 per cent of the medieval city centre, along with much of the Ralfses’ house and the art still stored in the basement. Otto’s famous guest book miraculously survived, along with a few artworks that were stored in a different part of the house.

It isn’t entirely clear what happened to the art kept in the Ralfses’ depot. The Red Army reached Katowice in January 1945 but, before any of the artworks could be confiscated by either the Soviet troops or the soon-to-be founded communist Polish state, the collection had vanished. “The entire warehouse had somehow seeped away into the population” was how Käte put it more than three decades later.

The watercolour by Kandinsky, stored in one of these boxes in a folder along with other works on paper, was just one small sheet among hundreds of artworks by artists including Klee, Otto Dix and Edvard Munch taken from the Katowice depot. The Ralfses would spend the rest of their lives trying to retrieve them.

Dorota Folga-Januszewska was a curator at the National Museum in Warsaw in 1982. In early summer, she and Irena Jakimowicz, then curator of modern prints and drawings, heard that a few modern pieces by famous western artists had appeared on the market. This was unusual at the time, but the museums had first dibs on the pieces, so they visited the state-owned Desa gallery in Krakow to view them. Lying in a vitrine were four works by Paul Klee and two by Wassily Kandinsky, an untitled drypoint from 1928 and the little pink watercolour, both with dedications to Otto Ralfs.

On a video call, Folga-Januszewska, now a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, told me she looked into the provenance of the pieces. Her investigations confirmed the obvious: the collection had once belonged to the Ralfses. Folga-Januszewska had heard rumours about where the artworks had come from but the official line was that they had been confiscated by the Nazi party and sold during the time of German occupation. In other words, they were not looted by Poles, nor requisitioned by the Polish state, but bought legitimately at the time. Folga-Januszewska and Jakimowicz submitted their purchase request for the works. The Kandinsky watercolour was bought for 500,000 zlotys (about £11,480 today).

Protests against the state were rife in Poland during this period, with widespread support for the strikes and demonstrations organised by the Solidarność (Solidarity) movement. The National Museum staff in Warsaw were also deeply engaged in Solidarity’s actions, said Folga-Januszewska, organising exhibitions to demonstrate opposition to the communist regime. In late 1982, the museum’s famous director Stanisław Lorentz was ousted after 50 years in the job, on account of his support for the protests. The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage replaced him with Juliusz Bursze, a paintings conservator and head of conservation at the National Museum.

In spring 1984, Folga-Januszewska installed the exhibition Concepts of Space in Contemporary Art at the National Museum. Included in the show, in the section of abstract works aptly titled “The Abandoning of Objects”, was the 1928 watercolour by Kandinsky, two other works by him and three pieces by Paul Klee, which had also belonged to the Ralfses’ collection stored in the Katowice depot.

"The official line was that the art was sold during the German occupation

In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, the curator’s words seem to perfectly describe Kandinsky sitting in his studio in 1928, manifesting his philosophy in abstract form: “Every artist bent over a sheet of paper, over a surface on which an image is to be created, answers anew the same question: how is the three-dimensional space of objects and the four-dimensional space-time of events rendered on a two-dimensional surface? Depicting the world on a surface, the artist transforms multi-dimensionality into two-dimensionality, which gives evidence of the individuality of his intellect and sensitivity.”

Folga-Januszewska left to go on holiday after the opening. When she returned, the Kandinsky watercolour was gone. “The atmosphere was strange,” she said. “As a curator, I wanted to know what had happened, but nobody wanted to talk about it. The Militia didn’t want to hear any questions, nor Juliusz Bursze.” According to the Polish Ministry of Culture, the theft took place on June 14 1984 and was reported to the police on the same day. “It felt to me like an organised event,” said Folga-Januszewska. “It was widely known that the secret police in Poland were smuggling goods back and forth across the border to make money.”

The black market for looted artworks in Poland after the war was enormous, said Nawojka Cieślińska-Lobkowicz, an art historian, critic and provenance expert on looted Polish and Jewish art and libraries. “Many people were leaving Poland in the 1980s. You have to understand the time, then you can see why an art historian, for example, might take a piece of art across the border and sell it in the west. Anyone could have taken the Kandinsky watercolour from the exhibition. It could have been someone who wanted to emigrate,” she said.

The Polish police closed the case on September 24 1984. By December of the same year, the three-dimensional object that was Kandinsky’s watercolour had travelled through space and time across the Iron Curtain to Sotheby’s in London.

As I mapped the journey of the little Kandinsky, a set of imagined characters began to form in my mind, each stealing the artwork from Warsaw and travelling with it, unframed, across one of the most heavily secured borders in history. It is an easy object to smuggle. It slots into a book, in a pocket, in a suitcase. It slips out of sight. Did the same person who stole it take it across the border? Were they in a car? Sometimes it’s a woman, sometimes a man. Sometimes it’s a Polish official, sometimes a secret service informer, sometimes an art historian or a person trying to emigrate. Perhaps it travelled directly to London or maybe it went via Munich.

On December 5 1984, the Kandinsky watercolour was sold at a public auction at Sotheby’s in Bond Street for £34,100. The catalogue from the auction is littered with curious errors. It misspells “Otto Ralff” as a previous owner. It locates him incorrectly in Munich. And it omits any mention of the National Museum of Warsaw or the presence of the museum’s stamp, which was on the back of the artwork. Missing, too, is any mention of the seller, as though the artwork had come through some direct channel from Ralfs. Sotheby’s has a record of the seller’s identity but declined to share it on grounds of client confidentiality when I asked, some 40 years after the sale. In a statement, it said: “Sotheby’s was instrumental in helping establish the Art Loss Register in 1990 and we check all property offered for sale against all available records of lost or stolen art.” It added that the catalogue for the 1984 sale of the Kandinsky, which was not registered as stolen at the time, “did not imply direct provenance from Otto Ralfs”. It was “not able to speculate as to whether the stamp was visible at that time”, as staff from that period no longer work at the auction house.

Charles Hind is chief curator and curator of drawings at the Royal Institute of British Architects. A cataloguer in the British watercolours department at Sotheby’s in the 1980s, he described to me the likely scenario for acceptance of an artwork such as this one. “Whoever the vendor was, maybe they came to the front desk,” he said, “and they must have come up with a story that was convincing but not important enough to merit inclusion in the catalogue. Something like, ‘Oh my mother bought it at a London gallery in the ’50s.’ That was common — and sometimes perfectly true.”

Back then, before the rise of postwar restitution claims in the 1990s and the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art, thorough and accurate provenance research was not so heavily obligated. “It was used to establish the history of an object,” said Hind. “It could add value and be used as a marketing tool, and it could demonstrate that the object had not been hawked around the open market. What the market loved — and still loves — were materials fresh to the market, and provenance was a useful way of proving that.”

Even today, the rules around provenance research for the selling of art are hazy, as the sale of the Kandinsky last year at Grisebach shows. In Germany, since the 2016 Cultural Property Protection Act, auction houses have been legally obliged to carry out thorough provenance research as part of their commercial operation, particularly where the artwork is suspected to have been taken from its owners due to Nazi persecution, between 1933 and 1945. The gaps in the provenance of the Kandinsky watercolour listed in the Grisebach catalogue suggest that, without knowing the facts, this could have been a possibility. But although Grisebach has 40 experts for this purpose, the data published in the auction catalogue for the Kandinsky watercolour was incorrect. It was based on inaccurate data published in the 1994 catalogue raisonné, the definitive list of an artist’s works.

As Hind pointed out, the Sotheby’s staff in 1984 had no such resource at their disposal: “The fact that [they] misread the collector’s name suggests that they didn’t devote a lot of time to it, [but] then again, there were hardly any places you could go at the time to check this. If something was established as stolen, we immediately withdrew it.” In its statement, Sotheby’s said: “Although it is now routine practice to photograph both front and back of works consigned for sale, this was not the case in the 1980s.”

In Hind’s department, the policy was always to open the frame and check the back of the artwork. “If they had, quite possibly alarm bells should have rung. But even if they had seen the stamp, there was no information available at the time about the theft, and relationships across the Iron Curtain in 1984 were very difficult,” he said.

A database of stolen art did exist at that time. And, in November 1985, just under a year after the sale at Sotheby’s, the National Museum in Warsaw contacted the International Foundation of Art Research (IFAR), which duly published a theft alert on the Kandinsky watercolour. In it, the IFAR stated that the museum was aware of the sale at Sotheby’s but had not yet contacted the auction house. It is unclear why this never happened.

The buyer took the watercolour to New York. Whoever it was, the title was not passed on to them at the point of purchase. “In English law, a thief cannot pass on good title,” said Emily Gould, assistant director of the Institute of Art and Law. Despite this, without a claim from the original owners (which, in England, should be made within six years of the sale), buying and selling of the Kandinsky continued through the art market. With every passing year, the ownership of the new buyers starts to gain in legitimacy in various jurisdictions. “Limitation periods [which vary in different territories] are one of the biggest hurdles for claimants for works that were looted during the second world war,” said Gould.

In the 1970s, the art market became a booming global network. Over the next few decades, works were increasingly seen as financial assets, with the prices paid for artists like Kandinsky rising accordingly. In 1931, his oil painting “Deepened Impulse” was listed for sale at 4,000 reichsmarks (£15,800 today) by Otto Ralfs during the collector’s period of insolvency. After Diego Rivera, the Mexican artist, decided he couldn’t afford it, it was bought in the same year by Salomón Hale, a Polish collector living in Mexico. Between 2010 and 2019, the painting was sold three times, finally for almost £6.1mn.

At the end of August this year I called an art dealer in Munich. Galerie Thomas, which specialises in modern and expressionist art, is located in the heart of the city, right next to one of Germany’s biggest museums of modern art, the Pinakothek der Moderne. In 1988, it became the next brief stop for the Kandinsky watercolour, which had travelled through London and New York. Like everyone else, the gallery was reluctant to name names. “It was a New York dealer, with a good eye and good works . . . now deceased,” said Silke Thomas, the daughter of the gallery’s founder. Galerie Thomas exhibited the watercolour in a show of miniature artworks. The watercolour was on the front cover of the matchbox-sized catalogue. “It was such a gem we didn’t have it for long,” she said.

"With every passing year, the ownership of the new buyers starts to gain in legitimacy

Thomas did not appear to see why anything about the sale of an artwork like this should be problematic. “We buy artworks and sell them on,” she explained. In German civil law, good title can be acquired by the buyer even if the seller does not own the work, unless the buyer is negligently ignoring their suspicion that the seller does not legally own it. In addition, there is no legal obligation to investigate the title of the seller. I asked if there was proof that the work was bought by the previous owner, and by Galerie Thomas, in good faith. She said the fact that it had been sold by Sotheby’s was effectively a guarantee. In Germany, auction houses are legally accorded an “auction privilege” by which rightful ownership, or “title”, is automatically conferred from seller to buyer if a sale takes place in a public auction. This law does not apply in the UK.

Neither Thomas nor Ralph Melcher, the gallery’s provenance researcher who was sitting in on our call, said they knew about the IFAR’s 1985 stolen-art alert. “Nobody was aware the work was stolen,” Thomas said. “Not Sotheby’s, not the dealer, not us, not Vivian Barnett, who wrote the catalogue raisonné. It’s not clear that it was stolen. It went through public auction.” I asked if they had seen the stamp by the National Museum in Warsaw on the back of the watercolour. Thomas said that they didn’t have any record of the stamp in their archived notes, so they probably didn’t notice it. “Everyone was doing as good a job as they could with what they had at the time,” she said.

The last owner of the little Kandinsky is known publicly. The billionaire Inga Maren Otto bought it from Galerie Thomas in 1988. She is the widow of Werner Otto, an entrepreneur who founded a mail-order empire in postwar Germany. Otto kept it in her collection for the next 34 years, until last year. In that time, the artwork’s legal status underwent its final transformation. Through the mere passing of time, the slate was wiped clean. Despite the historical, mass-scale plundering of cultural-heritage objects in and outside of its borders, in German law after 10 years the owner of a moveable item acquires the property if it was owned in good faith. The statute of limitations for claims for restitution of property is 30 years. By the time Otto consigned the work to Grisebach in 2022, she owned it fair and square.

Otto Ralf’s art collection was never far from his mind. “I think about it every day,” he wrote in a letter to the art dealer Ferdinand Möller in 1946. In 1955, Otto died in a car crash, which Käte survived. Afterwards, she continued trying to retrieve their stolen artworks, at one point hiring an art detective to whom she offered a 50 per cent finder’s fee to recover the collection. It was no use. She got stomach ulcers and tried to let go, but every now and then, she saw her artworks appear in galleries and auction houses in Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. “Die trauernde Braut” (“Mourning Bride”) by Otto Dix turned up at Galerie Nierendorf in Berlin, but when Käte Ralfs tried to confront the owner, he refused to tell her where he’d got it from. It was sold at Sotheby’s in 2008 for $62,500, with no mention in the provenance that it had once belonged to Otto and Käte Ralfs and came from the depot in Katowice, despite it being published on the German Lost Art Database, which has been publicly available since 2007.

Sotheby’s said the catalogue raisonné for Dix’s works features a series of six watercolours of grieving or mourning widows. “Only one of the six works has the specific title “Die trauernde Braut”, the work Sotheby’s sold in 2008, but, as you can see, the six watercolours are all variations on the same theme. Based on the fact the works are a series and incredibly similar in appearance, and that there is no image [on the German Lost Art Database] of the Dix registered as a loss to Otto and Käte Ralfs, Sotheby’s cannot identify the work we sold in 2008 as the same work registered with the German Lost Art Foundation.”

Käte had no money to push aggressively with lawsuits and, at the time, it was unclear what was legally possible. Even if she could have sued the dealers and auction houses selling her artworks, so much evidence had been destroyed in the Braunschweig bombings. Sometimes she caught a glimpse of the works still in Poland, where, it seemed, the majority of the collection hid. In the early 1950s, two Polish professors based in Krakow, Kazimierz Wojtanowicz and Włodzimierz Hodys, tried to sell works by Paul Klee from the Katowice depot in Germany. Klee died in 1940, so they contacted his son Felix for an appraisal of the works. They told him there was a box of Klees sold “under the table” and they had bought some with dedications to Otto Ralfs for themselves. Felix Klee informed Käte Ralfs, but when she contacted the professors, they denied owning the works.

The list of artworks belonging to the Ralfses’ collection — both those that stayed in Braunschweig and those transported and stored in the depot — is almost impossible to track down, but it was made available to me from the family archive. Many of the works on this list are also named on the German Lost Art Database website. In the case of Kandinsky, who died in 1944 near Paris, his untitled works, such as the pink watercolour, are listed as “a folder of watercolours and drawings”. Klee, who gave titles to his works and created small print-runs of his prints, is much easier to trace.

"The National Museum in Warsaw still owns nine works from the Otto and Käte Ralfs collection

On May 30 2019, Grisebach sold a Klee drawing from 1927, “Two Souls Up”, at a public auction. The artwork, previously acquired in the mid to late 1950s by a collector in Basel, is listed in the Lost Art Database as belonging to Otto and Käte Ralfs. It is also on the private list of looted artworks that were housed in the depot. Diandra Donecker, director at Grisebach, informed me that the auction house “does not consider the Ralfs’ provenance in itself to be problematic or to hinder trade. The mere entry of a search report for a work of art in Lost Art Database in no way renders a work of art unsellable. It is the circumstances in detail, which must be precisely examined and evaluated by an art dealer, that then determine the further course of action in accordance with the law.” The law is on their side.

Today, artworks from the Katowice depot can be seen in countless private and museum collections across the world, including the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The National Museum in Warsaw still owns nine works from the Otto and Käte Ralfs collection, including a pen drawing by Klee, dedicated to Käte Ralfs on her birthday in July 1928. Many other artworks on the depot list are lost entirely for now.

In the aftermath of the Kandinsky watercolour auction at Grisebach, the auction house reassessed what seemed to be its legal certainty about the transaction. It announced it would suspend processing the sale “to obtain a binding clarification”. Since then, the buyer, who remains anonymous, has pulled out. Grisebach did not respond to requests for comment.

The legal clarification is ongoing and, since there is no court hearing registered, this is happening behind closed doors, like almost all art-market disputes. What has come to light is that the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage is not involved in this clarification process. In a statement it said: “[D]espite EU and international obligations, to date the results of the investigation of [the] German authorities dealing with the case of the stolen Kandinsky watercolour have not been made available to [us].” It restated its position regarding the artwork’s legal status. With the ownership stamp still on the back, it said, “no civilised law can legalise such theft”.

Käte Ralfs died in 1995. The Ralfses’ heirs continue to live with remnants of the lost art and the evidence, built up over decades, of the family’s efforts to retrieve it. Artworks still pop up at auction, always several anonymous buyers and sellers removed from the looted collection. In the chain of provenance, a gap exists. For the Ralfses and family, that gap is profound. Artworks, for collectors like them, are personal, taken in as part of the family and remembered, long after the statutes of limitations are up. They can’t let go. And why should they?

Imogen Savage is a writer based in Berlin

ft.com/content/54270b2e-574a-400d-8abb-f87fb1a8e026