News:

The Nazis stole my art

By David Toren

The death yesterday of Cornelius Gurlitt, who inherited a huge collection of stolen masterworks, was only the latest chapter in a multi-decade ordeal for my family.

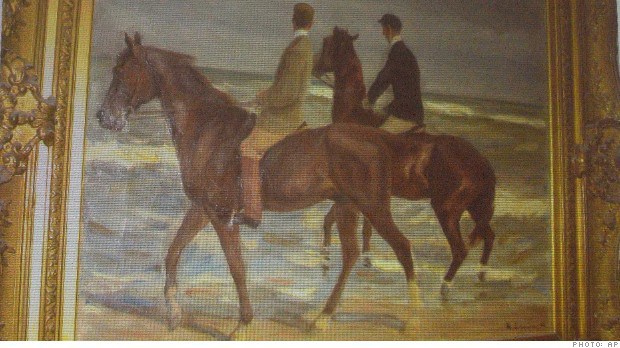

"Two Riders on the Beach" by Max Liebermann

Early in March I commenced legal action in the Federal District Court of Washington, D.C. against the Federal Republic of Germany and the state of Bavaria for the return of a number of master paintings which belong to my family but were stolen by the Nazis in 1939.

I feel good and vindicated today. The filing of the lawsuit was, of course, picked up by the press, particularly the German press, and the reaction was gratifying. The most influential German paper wrote that my lawsuit changes the landscape: "It brings to an end the excuses, delays, and meaningless tactical maneuvers of Berlin and Munich." But I'm actually more happy with the reaction of German clients (I'm an intellectual property lawyer) and German lawyers with whom I have worked in the past. One of my clients emailed, "I am happy to see that your fighting spirit is not diminished and that there are survivors of the Nazi Holocaust that take on our government particularly if it tries to emulate the Third Reich's methods." Another wrote, "Congratulations, I wish I had your guts to go after our Government, which consists of a bunch of bureaucrats with a perverted view of morality and justice."

Some put the blame on the prosecutor who had been sitting for 18 months on some 1,400 paintings and drawings of the great masters of the 20th century without notifying the public, the media, or even his superior. Finally, one wrote, "Your lawsuit is a breath of fresh air. I wish I had your nerve. I would like to sue them myself, but I don't know how."

But let's start with the beginning.

I am Jewish and was born in 1925 in Breslau, then a large German city near the Polish border. (It was ceded to Poland after World War II and renamed Wrocław.) From 1933, when Hitler came to power, to August 1939, when my father sent me with a kindertransport to safety in Sweden, I lived under the Third Reich. It was a miserable experience for a boy who was prevented from pursuing or participating in all the things a boy likes to do. At that moment of youthful innocence, I felt my greatest loss was that I was not permitted to keep my two parakeets, Habakkuk and Zephaniah, since Jews were not allowed pets.

My father was a prominent lawyer and poet with a weekly column in the Breslau newspaper. He was very German, dabbled in politics, although not very successfully. He was a director of The Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith, the largest of the German Jewish organizations. His favorite association was Schlarafia, an international organization that still exists with headquarters in Prague. To become a member you had to have an artistic leaning. He was heartbroken when Jews were expelled. My mother was a champion tennis player, and she was thrown out of her club, but with some friends succeeded in forming a Jewish tennis club.

We were a small family. I had only one sibling, an older brother. I never had a cousin. I had two aunts and a grandmother and then, of course, there was Uncle David. He was actually my mother's uncle -- my great-uncle -- but my family referred to him as Uncle David. He was admired by everyone. He was not only kind, but he was also rich, very rich. He owned four agricultural estates. His combined landholdings were almost 10,000 acres, and he grew sugar beets, which were partly converted into sugar by his refinery while the remainder was distilled into various alcoholic beverages in his distillery.

He also owned a large and beautiful villa, which was furnished like a museum, in the best section of Breslau. There he lavishly entertained Breslau's elite and celebrities such as Richard Strauss, the composer, Hjalmar Schacht, the financial guru, and Walther Funk, the famous economist (who was also a friend of my father before joining the Nazi Party). Schacht and Funk were defendants at the first Nuremberg trial after the war. Funk received a long prison sentence, and Schacht was found not guilty.

Uncle David left the running of his estates to others, and he spent most of his time collecting art. As early as 1905 he had purchased a Max Liebermann painting, Two Riders on the Beach, which hung on a wall in his villa next to an interior garden. The room had no window; a lamp illuminated the picture. This painting was my favorite. I had learned riding on one of the estates, and the picture featured two attractive horses. His collection contained a number of French impressionists such as Courbet, Rousseau, Pissarro, and Raffaëlli, as well as a number of non-Jewish German painters who were popular at the time. He also had an impressive porcelain collection, particularly Meissen and pottery as well as Persian carpets and French antique furniture.

One day in December 1939, an official of the Nazi Economic Ministry appeared at my uncle's villa advising him that his art collection would be confiscated, according to a letter from a government official that I found decades later. (The letter concludes, "with kind regards and Heil Hitler!")

The official made a list of all the paintings, including Two Riders and another Liebermann work called The Basketweaver, as well as the various French impressionist pieces and other artworks mentioned above. Before leaving, according to the government letter, the official warned my uncle not to dispose of any of the artworks before he returned. Considering the atmosphere of the time it is unlikely that my uncle would have disobeyed this order.

The Third Reich was in dire need of hard currency since it had to pay for the importation of vast quantities of raw materials to build up the armed forces in preparation for war. The many laws and regulations, which had made life miserable for Jews -- such as the Nuremberg race laws of 1935 and the disbarment of lawyers and the restriction of physicians to treat only Jewish patients -- did not bring in any hard currency.

So Josef Goebbels was put in charge of confiscating valuable art, particularly master paintings from Jewish collections for sale abroad in return for hard currency. Some of these paintings were to be segregated for the future Führermuseum in Lins, Austria, which was to be the grandest museum in the world. The ministry of economics was put in charge of the actual confiscation of the artworks from the Jews, with Göring, the head of the Luftwaffe, acting as an art advisor to Goebbels.

Goebbels began looking for a man who could handle the sale of the stolen art in foreign countries, and the man he chose was Hildebrand Gurlitt. Gurlitt was an accomplished art dealer with an excellent reputation. He knew all the tricks of the trade and was known to have excellent taste. More important, he had widespread contacts throughout the world with other art dealers and art galleries. Gurlitt had a defect: a Jewish grandmother. Under ordinary circumstances this would disqualify him from dealings with Nazis, in particular the Nazi Leadership. But Goebbels decided to overlook this deficiency. He was quoted saying, "Jude oder niche Jude er ist mein mann." ("Jew or not Jew, this is my man.")

Gurlitt was thus entrusted with hundreds if not thousands of paintings and drawings stolen from German Jews, presumably including those of my uncle, and later from the Jews of the occupied countries. His task was to sell as many of these artworks abroad and with the help of Goring to decide which artworks were to be reserved for the Führermuseum.

There is no information as to the success of his mission. However, since Hitler occupied large parts of Europe in 1940 and Gurlitt came on the scene in only 1939, he didn't have much time to sell the artworks. Art dealers in the occupied countries like France, Holland, Denmark, and Norway were mostly Jewish, and the artworks owned by them were confiscated while they themselves usually ended up in the concentration camps and ultimately the gas chambers. Thus Gurlitt's clientele shrank after 1940. Most of his remaining clients were in Sweden, Switzerland, the United States, and South America.

By this point my uncle wasn't around any more. He died of natural causes in 1942. The next year my parents died in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Near the end of the war Gurlitt had some 1,700 artworks left. He couldn't give them back to Goebbels because, in May 1945, the Propaganda Minister poisoned himself, his wife, and his six children. So Gurlitt kept the artworks and hid them in a castle in Bavaria. When he was confronted by the Monument Men, a group of art experts established by the allies to search for looted art, he contended that all the paintings had been legitimately acquired. When asked for documentation he stated that he had been living in Dresden and that all documentation was destroyed during the well-known air raid by the British during the end of the war.

As to the Two Riders by Liebermann, he contended that the painting had belonged to his grandparents. The Monument Men didn't believe him and confiscated his treasure trove. Hildebrand Gurlitt, being a smart man, now converted a detrimental Jewish grandmother into a billion-dollar asset. He told the Monument Men that under Nazi race laws he was a Jew. How could a Jew have been a Nazi? He claimed he collaborated with the Hitler crowd only to save his life and had he refused to deal with them he would have been sent to the gas chamber.

The Monument Men, some of whom were Jewish, believed him and returned the stolen art, including Two Riders, to him. He was now a free man with a billion-dollar collection and started to reestablish his somewhat tarnished reputation by giving lectures and holding seminars. When he needed money, he sold a painting. He was killed in a car accident in 1956, and his son inherited the treasure trove.

The son, Cornelius Gurlitt, moved with his art into an apartment in Munich and adopted the life of a recluse. He hardly ever went out, shunned friends and women, and took taxis when he had to buy groceries in a store 200 meters away.

His problems started, many decades later, on a train trip from Zurich to Munich. A customs official on the train seemed to remember Cornelius Gurlitt as having been on the same train a few hours earlier in the opposite direction from Munich to Zurich. He figured that the thin, white-haired man had gone to Zurich to withdraw money from a bank and was now on his way back to Munich. He asked Gurlitt how much money he had on him, and Gurlitt responded, "very little." A check of his wallet showed he had €9,000, although this was not illegal since travelers were permitted €10,000 without making a customs declaration.

But the customs official was still suspicious because Cornelius stated that he had no job. Where did he get all this money from? Was he a money-launderer or smuggler? The official notified the tax authorities in Munich who established that Cornelius had never paid taxes, did not own a bank account in Bavaria, and did not draw on benefits from Bavaria to which he would be entitled.

They notified the prosecutor's office, which assigned the case to the prosecutor of Augsburg. The Augsburg prosecutor raided Cornelius Gurlitt's apartment and was astounded to find more than 1,400 works by famous artists. He confiscated all of them and transported them to a secret location in Augsburg. For the next 18 months, the prosecutor did nothing. He did not advise the public, the media, or even his superior of the existence of this trove. It was a leaker who notified a journalist, who in turn alerted Focus, a newsmagazine. Focus' article broke the story, and the media pounced on it, bombarding the prosecutor with questions. The prosecutor called a press conference on Nov. 5, 2013. It was a press conference and not a news conference because hardly any news was divulged. He promised to rush the resolution of the matter by determining the provenance and ownership of the many artworks. To throw the many journalists a bone, he showed five paintings to the audience, one of which was Two Riders.

I did not watch the press conference because I've been blind since an illness in 2007. But a German lawyer who was looking for Two Riders and had listed the painting on the lost art website several years ago advised me that the painting had reappeared at the press conference. He immediately filed a claim on my behalf. After the press conference, nothing happened. The German government was embarrassed because it was obvious that many of the paintings in the collection had been stolen from German Jews, and they did not want to handle this matter that was so reminiscent of Hitler's time.

They were pressured by several governments, such as those of the U.S., France, and Israel, as well as by many Jewish organizations, which pointed out that the delay of 18 months caused by the prosecutor was very detrimental to the heirs of the artworks since the heirs by necessity were also of advanced age. I myself am 89, and my brother, who was a co-heir, was 93 when he passed away last month.

The German government then assembled a task force to examine the paintings with a view to establishing provenance and ownership. The task force containing members of different agendas, mainly art historians, as of April 1 had not decided where to meet, what procedures to follow, and whether decisions had to be unanimous or by a plurality. By that point I had decided to light a match under the task force's feet and instructed a Washington law firm to investigate whether I could sue the German government and Bavaria in a U.S. court and whether my chances to succeed were reasonable. The result was a lawsuit filed in the district court in Washington, D.C. I understand that I am the only heir to have taken such a step.

After the complaint was filed, we have to serve it on the defendants, which is a complicated procedure governed by the Hague convention for the service of judicial and extrajudicial documents. That is the stage we have reached. But according to the governing law, the Foreign Sovereign Immunity Act, Germany can refuse Hague convention service. I have been told that Germany is in the habit of doing so. But that would not be the end of the story. I can then give the complaint to the U.S. State Department, which must serve the papers on the foreign office in Berlin. They are not permitted to refuse service and have to decide whether to file an answer or make a motion to dismiss.

As can be seen it is not easy to sue the German government and get justice in a straightforward manner. Two Riders and the other French impressionist paintings are heirlooms belonging to my family, and the unconscionable delay tactics of the German Government should not be tolerated. I feel an obligation to pursue our family's claim.

P.S. The landscape changed again in the beginning of April, when Germany reached an agreement with Cornelius Gurlitt to return the art to him, except for those pieces suspected of having been stolen from the Jews. The task force will attempt to determine the provenance and ownership of those paintings -- as reported, about 600 -- within one year. Gurlitt agreed that if ownership and provenance have conclusively been determined, then the paintings in question can be returned to the heirs of the original owners. The press release on the agreement does not state what is to happen with artwork for which no claim has been made so far.

Whatever hopes were raised by that agreement may be transient. Yesterday, less than a month after the agreement was announced, Gurlitt died at 81. My lawyers say it's not clear whether the agreement will apply to any heirs he might have. Gurlitt will no longer resist turning over the stolen art. I hope we'll be able to say the same about the German government.

Editor's note: After this article was published, multiple news outlets reported that a Swiss museum, the Kunstmuseum Bern, was revealed as Gurlitt's sole heir. Subsequently, the Wall Street Journalreported that the museum plans to return any looted art.

http://features.blogs.fortune.cnn.com/2014/05/07/the-nazis-stole-my-art/