News:

This Real-Life Sherlock Holmes Hunts Down Stolen Nazi Art

By Elisabeth Kulze

In the past two decades, Chris Marinello has recovered $350 million worth of stolen and looted art, including several priceless works the Nazis plundered during WWII

When German authorities descended on a cluttered, unassuming Munich apartment in March of 2012, they uncovered a stash of some 1,500 paintings and drawings that had been kept from the public eye for more than 70 years. The collection, which was valued at $1 billion, included masterpieces by Chagall, Picasso and Matisse, and was in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt, the 80-year-old son of a prominent dealer of Nazi-looted art.

Many of the paintings had been taken from distinguished Jewish art collectors and gallerists as part of the Hitler-mandated plunder that occurred throughout World War II, and among them was a Matisse that had belonged to Paul Rosenberg, a renowned Parisian art dealer and personal friend of the artist.

So after a German magazine feature broke the historic discovery in November of last year, the Rosenberg heirs set about getting the Matisse back with the help of Chris Marinello—one of the world’s most experienced art hunters and restitution experts. As the founder of Art Recovery International, a London-based company that specializes in returning fine art pilfered by Nazis and modern-day criminals, the 52-year-old, Brooklyn-born attorney has located and recovered some $350 million worth of stolen and looted art in his 20 years on the job.

“Some of the biggest cases we’ve got going on right now are some of the biggest cases in the world in this area,” Marinello says. “A 30 million euro piece in Italy, a 10 million euro Crivelli in Portugal, the Gurlitt case, and we have some other Matisses. I think I’ve recovered five or six Matisses over the years.”

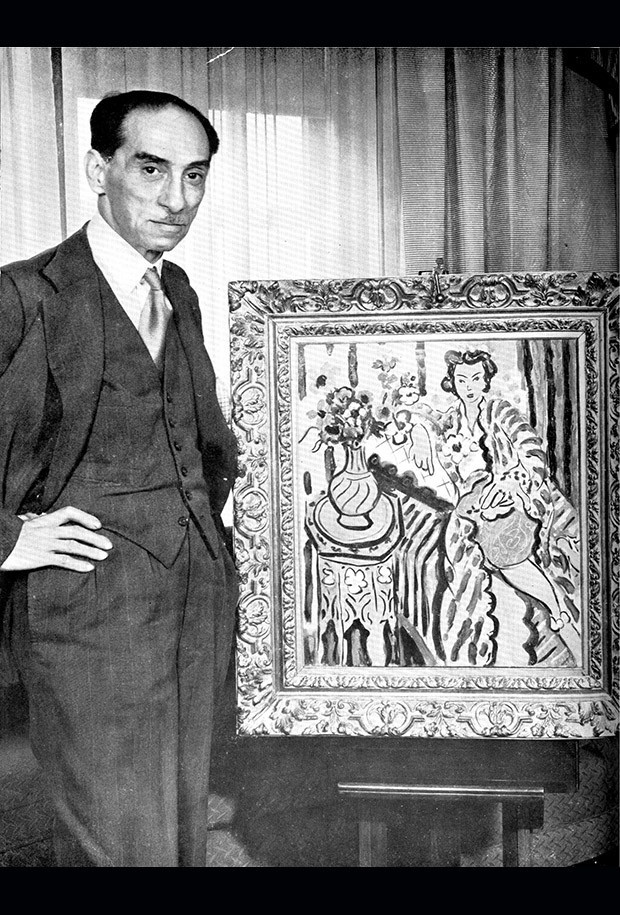

Chris Marinello with Matisse’s “Woman in Blue in Front of a Fireplace" after a Norwegian museum agreed to return the painting to the Rosenberg family. Photo Courtesy Chris Marinello

Chris Marinello with Matisse’s “Woman in Blue in Front of a Fireplace" after a Norwegian museum agreed to return the painting to the Rosenberg family. Photo Courtesy Chris Marinello

Marinello is one of a small handful of lawyers around the world who work in this area, and last Friday many of them gathered in New York for NYU’s Art Law Day, a conference dedicated to the intersection of law and the art market.

A sharp-suited Marinello and I meet at a café following his panel on restitution, which featured Christie’s director of stolen art, as well as Marianne Rosenberg, the granddaughter of Paul Rosenberg. Marianne is currently leading the decades-long fight to recoup hundreds of paintings stolen from her family by the Nazi regime; as of today, around 60 paintings from the Rosenberg collection are still missing, along with nearly 100,000 works of art that belong to other families.

In the past 15 years Marinello has helped the Rosenbergs recover one of Monet’s “Waterlillies,” which was found hanging on the wall of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts during a Monet retrospective, as well as Matisse’s “Woman in Blue in Front of a Fireplace,” which was discovered as part of a Norway museum’s permanent collection. Today, Marinello and the Rosenbergs are embroiled in the battle for the Matisse from the Gurlitt trove, which has faced enduring complications, including the death of Gurlitt himself in May of this year.

Retrieving Nazi-looted art is never easy. You can’t just ask for it back. First there is the task of proving provenance (art world jargon for history of ownership) decades after the crime, and once you do that, the current owner—be it a museum or a private buyer—is not even legally obligated to return it. The only existing statutes that deal with how countries should handle Nazi-confiscated art—known as the Washington Conference Principles—are nonbinding.

To make matters more difficult, in most cases the people who end up with this art are known as “good faith buyers,” implying that they bought the pieces without knowing they were stolen. Ultimately, this means that Marinello, despite being a lawyer, is unable to depend on the law for much of the work he does. Instead, he is compelled to rely on the more tenuous forces of morality, ethics and politics in order to convince people that retuning a painting is in their best interests—what he calls “creative solutions.”

For example, with the Rosenberg Matisse found on the museum wall in Norway, “This meant going to the Norwegian ambassador to the U.S. and having a long discussion about what Americans would think of Norwegians living here, and the consequences for publicity and the tourism industry if Norway was seen to claim that Norwegian law allowed them to keep a Nazi-looted painting from a family,” says Marinello. “We made them very aware of this, and we did get some assistance from political leaders, both in the U.S. and in Norway, that encouraged the parties to work out a settlement.”

Art dealer Paul Rosenberg pictured next to Matisse's "Odalisque with Yellow Persian."

Finding the missing art in the first place is also a major undertaking. The Gurlitt case was unique in that the media brought the painting to Marinello, but most of time his team locates a stolen work even before law enforcement. To do this, they rely heavily on proprietary technology called ArtClaim, a private, comprehensive database of lost, stolen and looted works of art from around the world.

After a missing item is entered into the database, Marinello’s team then uses image recognition software to scour the catalogs at Sotheby’s, Bonham’s, eBay and other auction venues, until they find a match. From there, they will either notify law enforcement if the item was recently stolen, or contact the dealer or auction house to notify them that the work they are trying to sell is actually Nazi loot.

There are also cases where Marinello’s team is directly involved in helping the police or government agency catch a criminal.

“We had a major case in Prague where a photograph was taken from a museum, and it was worth about half a million dollars,” says Marinello. A few days after it was stolen, Marinello was contacted by someone who was offered the work. “We posed as potential buyers, and we convinced the seller to send the item to us. Two weeks after the theft, we had it back on the wall of the museum.”

A U.S. soldier views art stolen by the Nazi regime and stored in a church in Ellingen, Germany, on April 24, 1945. REUTERS/U.S. National Archives

Eighty years after the Nazis’ plunder rampage, art is still a frequently stolen commodity—the third highest-grossing criminal trade, behind guns and drugs. The value of paintings and art has risen dramatically in recent years (two Mark Rothko paintings just fetched over $76 million at a Sotheby’s auction yesterday), and it also remains relatively easy to steal.

“A small painting here or a small object there—it’s easy to hide,” Marinello says. “It’s easy to transport from one place to another because it’s not inherently illegal. Someone sitting in an airport next to a painting is different than someone sitting next to a gun or a bag of cocaine.”

Marinello’s hope, however, is that technology will make it increasingly difficult to sell stolen art, which is a thief’s ultimate goal. Early next year the ArtClaim database will be made available to the public, with the intention of making it easier for buyers and sellers to check whether or not a work was stolen. And once more people are made aware of a work’s tainted provenance, the industry is unlikely to touch it for fear of reputational damage.

“Stolen art is genuinely worthless in a legitimate marketplace,” Marinello says.

Apart from making the art market a more honest and transparent one, Marinello is also helping many people heal. And not just prominent families like the Rosenbergs; Marinello does a lot of pro-bono service for Holocaust victims who had culturally and emotionally significant work looted from their homes during the war.

In 2008 Marinello and his team were able to track down an Anto Carte portrait of a little girl holding a bunny that had been taken from her family’s home in Brussels after they fled during the Nazi occupation. At the time, it was being offered for sale in New York, and with the assistance of the FBI, Marinello was able to set up a sting operation and recover the painting. He went to Belgium the following year to reunite it with the family, which included the girl in the painting—now an old woman—who had posed with her fluffy pet so many years before.

“It gives us a great deal of satisfaction to reunite victims with their lost possessions because in many cases, especially with victims of the Holocaust, they’re not just possessions,” Marinello says. “They are symbols of the loss suffered by their family at the hands of the Nazis. They’re getting a little piece of their lives back that was taken away from them in a very brutal way.”