News:

Norton Simon's disputed 'Adam and Eve' getting closer look from Supreme Court

LA Times 4 October 2010

By Mike Boehm

The U.S. Supreme Court wants a top federal lawyer to weigh in on the question of whether Holocaust victims and their heirs should be bound by a statute of limitations deadline when suing California museums for the return of Nazi-looted artworks.

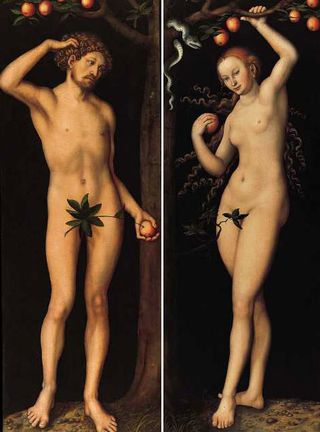

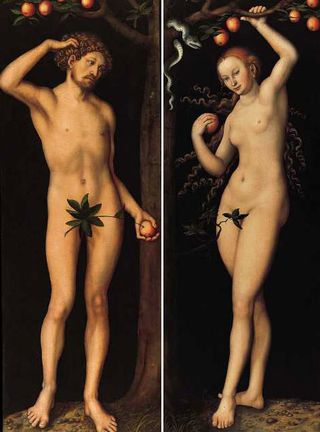

The high court on Monday denied, as it usually does, the vast majority of the requests it receives to take up appeals. But Marei Von Saher’s bid to reverse a pretrial decision that damaged her attempt to wrest Lucas Cranach the Elder’s 480-year-old “Adam and Eve” diptych from Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum is still alive. The court neither accepted nor declined to hear the case, but asked the U.S. Solicitor General, who represents the federal government in Supreme Court cases, to submit a brief on the government’s view of the matter.

Elena Kagan recently left the Solicitor General's post when she was confirmed as a Supreme Court justice; her former deputy, Neal Katyal, is the acting Solicitor General.

At stake is a masterpiece appraised at $24 million, and a voided state law aimed at ensuring that claims against museums and art dealers who own disputed works once looted by the Nazis are decided on the merits of the case, rather than whether a suit was filed in time.

A trial judge in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles dismissed Von Saher’s case in 2007. He ruled that the 2002 state law under which she sued the Norton Simon was an unconstitutional infringement of the federal government's prerogative to set foreign and war policy. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that the state did not have a right to suspend its statute of limitations on Holocaust-related grounds; it said Von Saher could still try to argue that when she first claimed the painting in 2001 she was within the ordinary three-year statute of limitations.

The museum already has said in court pleadings that Von Saher waited too long.

In her request for a Supreme Court hearing, Von Saher’s attorneys argued that the California law setting aside the statute of limitations for Holocaust art suits filed by Dec. 31, 2010, actually advances federal government policy rather than conflicting with it. Their petition quoted an address that Stuart Eizenstadt, the State Department’s special advisor on Holocaust issues, had given at an international conference last year: When “otherwise meritorious claims” are denied on statute of limitations and other technical grounds, Eizenstadt said, it “compounds the grotesque nature of the original crime.”

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger last week signed into law a new art-theft bill that doesn’t mention the Holocaust but gives all claims seeking the return of stolen art from museums, galleries and dealers a better shot at withstanding the legal argument that they were filed too late. In suits over allegedly stolen art and other scientific, historic and cultural artifacts, the statute of limitations has been extended from three years to six, and the six-year clock starts running when the plaintiff first learned where the object was. Previously, a museum could argue that the clock began running when a work’s whereabouts was first publicized to the extent that someone seeking its return should have known about it then.

"Adam and Eve" went on display in 1977 when the Norton Simon opened, prompting Los Angeles Times art critic William Wilson to write that he had experienced “a plain shock of unmitigated aesthetic fulfillment” upon seeing them. Museum founder Norton Simon bought the Cranachs from an heir of Russian aristocrats in 1971, and The Times first reported on them in 1972, saying they were among the industrialist's holdings that were being loaned to Princeton University for an exhibition.

Von Saher’s attorney, Lawrence Kaye, said Monday that her legal team, which includes E. Randol Schoenberg, the Los Angeles attorney who in 2006 secured the return of five looted Gustav Klimt paintings from the Austrian government, will wait to see whether the U.S. Supreme Court reinstates the voided California Holocaust art law. If it does not, she would be able to amend her suit to proceed under the state's new art-theft law. But the new law also would allow the Norton Simon Museum to use legal grounds other than the statute of limitations to press its argument that Von Saher waited too long to claim "Adam and Eve."

If the case ever goes to trial, it would focus on the painting’s journey over the past 100 years. Did it belong to the Stroganoffs, a family of Russian nobles, before the Russian Revolution of 1917 -- or to the church where it had hung before being declared national property by Soviet authorities? In 1931, the Soviets sold it to Jacques Goudstikker, a Dutch-Jewish art dealer and Von Saher’s father-in-law; there’s no dispute that the Nazis looted it from him in 1940, and that victorious Allied forces restored it to the Dutch government after World War II. But did an early 1950s settlement between the Netherlands and Goudstikker’s heirs extinguish their claim to “Adam and Eve”? If not, did the Dutch have a right to subsequently sell it to the Stroganoffs’ heir in 1966, after he claimed it as family property? And ultimately, does the Norton Simon have clean title to this masterpiece showing Adam and Eve moments before their fall? Or has it been tainted by a century’s historical sins?

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2010/10/art-adam-eve-holocaust-norton-simon-.html

By Mike Boehm

The U.S. Supreme Court wants a top federal lawyer to weigh in on the question of whether Holocaust victims and their heirs should be bound by a statute of limitations deadline when suing California museums for the return of Nazi-looted artworks.

The high court on Monday denied, as it usually does, the vast majority of the requests it receives to take up appeals. But Marei Von Saher’s bid to reverse a pretrial decision that damaged her attempt to wrest Lucas Cranach the Elder’s 480-year-old “Adam and Eve” diptych from Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum is still alive. The court neither accepted nor declined to hear the case, but asked the U.S. Solicitor General, who represents the federal government in Supreme Court cases, to submit a brief on the government’s view of the matter.

Elena Kagan recently left the Solicitor General's post when she was confirmed as a Supreme Court justice; her former deputy, Neal Katyal, is the acting Solicitor General.

At stake is a masterpiece appraised at $24 million, and a voided state law aimed at ensuring that claims against museums and art dealers who own disputed works once looted by the Nazis are decided on the merits of the case, rather than whether a suit was filed in time.

A trial judge in U.S. District Court in Los Angeles dismissed Von Saher’s case in 2007. He ruled that the 2002 state law under which she sued the Norton Simon was an unconstitutional infringement of the federal government's prerogative to set foreign and war policy. The U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that the state did not have a right to suspend its statute of limitations on Holocaust-related grounds; it said Von Saher could still try to argue that when she first claimed the painting in 2001 she was within the ordinary three-year statute of limitations.

The museum already has said in court pleadings that Von Saher waited too long.

In her request for a Supreme Court hearing, Von Saher’s attorneys argued that the California law setting aside the statute of limitations for Holocaust art suits filed by Dec. 31, 2010, actually advances federal government policy rather than conflicting with it. Their petition quoted an address that Stuart Eizenstadt, the State Department’s special advisor on Holocaust issues, had given at an international conference last year: When “otherwise meritorious claims” are denied on statute of limitations and other technical grounds, Eizenstadt said, it “compounds the grotesque nature of the original crime.”

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger last week signed into law a new art-theft bill that doesn’t mention the Holocaust but gives all claims seeking the return of stolen art from museums, galleries and dealers a better shot at withstanding the legal argument that they were filed too late. In suits over allegedly stolen art and other scientific, historic and cultural artifacts, the statute of limitations has been extended from three years to six, and the six-year clock starts running when the plaintiff first learned where the object was. Previously, a museum could argue that the clock began running when a work’s whereabouts was first publicized to the extent that someone seeking its return should have known about it then.

"Adam and Eve" went on display in 1977 when the Norton Simon opened, prompting Los Angeles Times art critic William Wilson to write that he had experienced “a plain shock of unmitigated aesthetic fulfillment” upon seeing them. Museum founder Norton Simon bought the Cranachs from an heir of Russian aristocrats in 1971, and The Times first reported on them in 1972, saying they were among the industrialist's holdings that were being loaned to Princeton University for an exhibition.

Von Saher’s attorney, Lawrence Kaye, said Monday that her legal team, which includes E. Randol Schoenberg, the Los Angeles attorney who in 2006 secured the return of five looted Gustav Klimt paintings from the Austrian government, will wait to see whether the U.S. Supreme Court reinstates the voided California Holocaust art law. If it does not, she would be able to amend her suit to proceed under the state's new art-theft law. But the new law also would allow the Norton Simon Museum to use legal grounds other than the statute of limitations to press its argument that Von Saher waited too long to claim "Adam and Eve."

If the case ever goes to trial, it would focus on the painting’s journey over the past 100 years. Did it belong to the Stroganoffs, a family of Russian nobles, before the Russian Revolution of 1917 -- or to the church where it had hung before being declared national property by Soviet authorities? In 1931, the Soviets sold it to Jacques Goudstikker, a Dutch-Jewish art dealer and Von Saher’s father-in-law; there’s no dispute that the Nazis looted it from him in 1940, and that victorious Allied forces restored it to the Dutch government after World War II. But did an early 1950s settlement between the Netherlands and Goudstikker’s heirs extinguish their claim to “Adam and Eve”? If not, did the Dutch have a right to subsequently sell it to the Stroganoffs’ heir in 1966, after he claimed it as family property? And ultimately, does the Norton Simon have clean title to this masterpiece showing Adam and Eve moments before their fall? Or has it been tainted by a century’s historical sins?

http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/culturemonster/2010/10/art-adam-eve-holocaust-norton-simon-.html

© website copyright Central Registry 2024