News:

Wheeler-dealer

The complicated story of how Hitler’s dealer hid his art

The Munich Art Hoard: Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy. By Catherine Hickley. Thames & Hudson; 272 pages; £19.95.

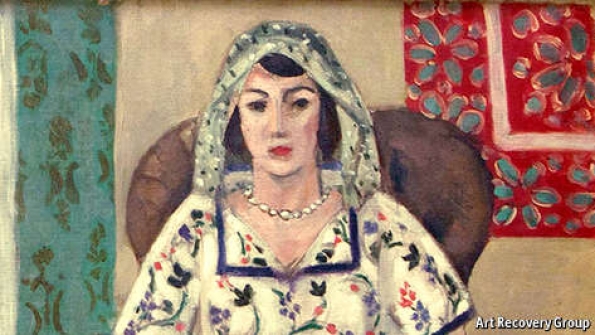

THE Nazis would willingly have destroyed, much as Islamic State (IS) does now, everything they regarded as Entartete Kunst, or “degenerate art”. This included many early 20th-century masterpieces, including “Femme Assise” by Henri Matisse (pictured), that were seized from museums and Jewish collectors and sold for foreign currency, which the Nazi regime needed, just as IS does, to finance its war machine.

Hildebrand Gurlitt became a facilitator of this process. Intelligent, with a well-trained eye and an appreciation of art that he inherited from his father, he enjoyed both the trust of prominent Jews and the confidence of Hitler’s ideologues. Gurlitt was himself a quarter Jewish, a small taint to his Aryan-ness that the Nazis were willing to overlook in order to take advantage of his connections in the art world.

Gurlitt was one of only four German dealers licensed to buy and sell on behalf of Hitler’s regime. He was a conduit by which despised “degenerate art” could be sold. He bought art cheaply from Jews fleeing from Germany. He purchased for the Führer’s projected art museum in Linz and also built up a big collection of his own. In short, Gurlitt saved much art, but he dealt in it while its rightful owners perished; he said he helped Jews, but he also profited massively from their misfortune.

This complex, shadowy story, and the subsequent fate of the art that Gurlitt handled, is painstakingly told in Catherine Hickley’s comprehensive narrative, “The Munich Art Hoard”. She does not linger long on issues of morality, but meticulously lays out the spidery network of ties, lies, pressures and fears that helped Gurlitt save his own skin and amass (and ultimately safeguard) a huge collection. When the hoard finally emerged in 2013 from the shuttered residences of his mild-mannered and socially autistic son, Cornelius, the discovery shocked the art world and raised a cloud of legal and ethical dilemmas. The reclusive Cornelius, who had thitherto felt his pathological solitude strangely comforted by his possession of the secret cache of art, found himself become an international cause célèbre.

There are passages in Ms Hickley’s account which display all the excitement of the best investigative journalism. But journalism it remains. The big issues which the story raises are all left unresolved, which is a pity. But perhaps the greatest pity of all is that while lawyers, bureaucrats and art historians continue to deliberate, several hundred works of art—many of the highest order and by artists as prominent as Monet, Manet, Courbet, Chagall and Munch—languish unseen in a vault in Munich. Arguments over legal repossessions will inevitably mean that many of them may not be seen again for decades. This is perhaps their only opportunity to be displayed all together. The German authorities have many responsibilities to bear. But the most easily discharged of all would be to let the world have the opportunity meanwhile to view this unseen art—raising public awareness thereby of the sheer scale of what happened in Nazi Germany and reminding people that looting and trafficking of art works still happens today.