News:

Why a Swiss gallery should return its looted Nazi art out of simple decency

By Jonathan Jones

Nazi loot carries a legacy of hate. The latest ownership dispute – over a Constable painting, claimed by the heirs of British Jews – reminds us that respect is at the heart of the restitution debate

Memory has many colours. A work of art that survives the centuries is an embodiment of history, marked invisibly by all the hands that have held it. Who owned it? Where did it hang? These are not just arcane questions for scholars but the network of human experience that haunts works of art in museums and makes them richly alive.

The hunt for works of art looted by the Nazis matters. Researchers who discover the true owners of a painting stolen in wartime Europe and later acquired innocently or knowingly by a museum or gallery are piecing together shadowy stories of oppression, injustice, murder and destruction. Why did the Nazis loot art from Jewish owners? It was not only greedbut an ideological belief that Jews contributed nothing to European civilisation and did not deserve to share in it.

Nazi loot carries a legacy of hate. And that is why a Swiss art museum is wrong to refuse to return a painting by John Constable to the despoiled owner’s rightful heirs. When Anna Jaffe died in France in 1942, she left the art collection of her late husband John Jaffe to her nieces and nephews. Mr Jaffe, whose brother Otto was a former lord mayor of Belfast and whose family were noted linen exporters, had settled in France – hence his ownership of a painting by one of England’s great artists. The stories of looted works of art reveal these hidden details of modern history: here was a work owned by an eminent British businessman, who moved to France and whose art collection ended up in the hands of the pro-Nazi Vichy government.

Constable’s painting Dedham from Langham was auctioned at a forced sale in Nice in 1943. Now the family of John and Anna Jaffe want it back – but the Musée des Beaux-Arts in La Chaux-de-Fonds insists it will keep the work, offering to tell the story of its provenance in a special gallery text on the wall instead.

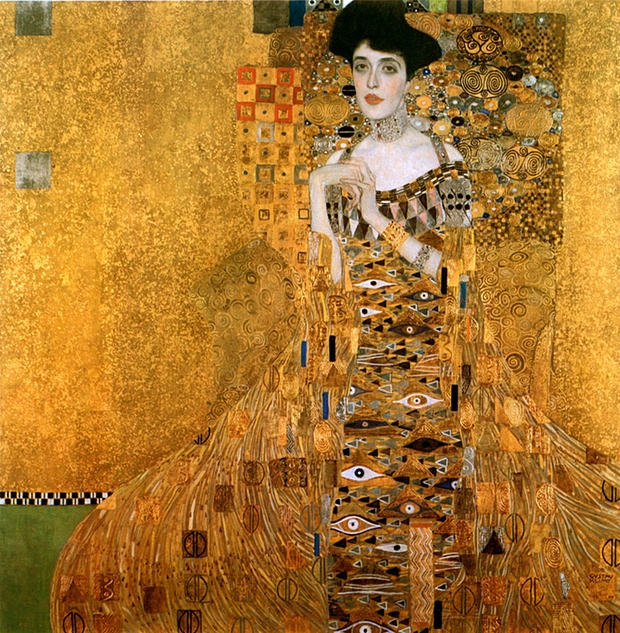

Is there a backlash against restitution in the museum world? In recent years some spectacular restitutions of looted art have led to masterpieces moving around the world. Most notably, Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, once a highlight of Vienna’s art collections, is now in the Neuegalerie in New York. But some museums are becoming more resistant.

Last year a panel in Austria voted to reject a demand for the return of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze to the heirs of Erich Lederer, who inherited it from his father August. In fact the case was complicated. Lederer survived the war and later sold the Frieze – Klimt’s masterpiece – at what the heirs claim was an enforced cut price. The Austrian inquiry rejected this claim.

The Swiss museum says it bought Constable’s painting in good faith and therefore should not have to return it. Switzerland was neutral in the second world war – it does not carry the direct burden of Holocaust guilt that Austria does. But why does that make it all right to cling to war loot? British galleries are more open about this. The National Gallery announced unprompted a few years ago that a masterpiece by Cranach in its collection was once in the hands of Adolf Hitler himself. No rightful owner has been traced, so it is still in the National Gallery – for now.

In the end, there is no case against the justice of returning works of art to their rightful owners when these can be found. No crime in history equals the Holocaust. Looting art was just one more way that Nazism denied the humanity and individuality of Jewish people. There is no “on the other hand”. It is our collective duty to uncover the lost histories of suffering hidden in museums masterpieces and where justice can be done, it should be done gladly, as a basic act of respect and decency.