News:

Stolen by a Russian spy, Dutch painting now returned to German museum

By Gaby Reucher

A work by a 17th-century Dutch master was smuggled to North American after World War II. After 75 years, it's been returned to the German museum where it belongs. Here's the tale of a painting that's fit for James Bond.

Museum director Peter van den Brink has known for a long time where Balthasar van der Ast's painting "Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase" was: It had belonged to a private collector in the US since 1973.

"I've known the collector for 30 years and have known the painting since then as well," he said.

In an exhibition in Delft, van den Brink had even touched it. But he'd had no idea that the 17th-century still life had been looted.

The story behind the work, which was originally part of the collection of the Suermondt Ludwig Museum in Aachen and then went missing for 75 years, is fit for Hollywood. Now, van den Brink has brought the painting back from New York and, as of Monday, it is available to be viewed by the public in the museum's so-called Fireside Room.

Van den Brink estimates the painting's present value at 4 million euros (over $4.5 million). Balthasar van der Ast was among the best-known still life painters of the 17th century. Flower paintings were en vogue at the time - particularly those depicting exotic flowers and exclusive imports such as the Chinese Wan-Li vase seen in the van der Ast.

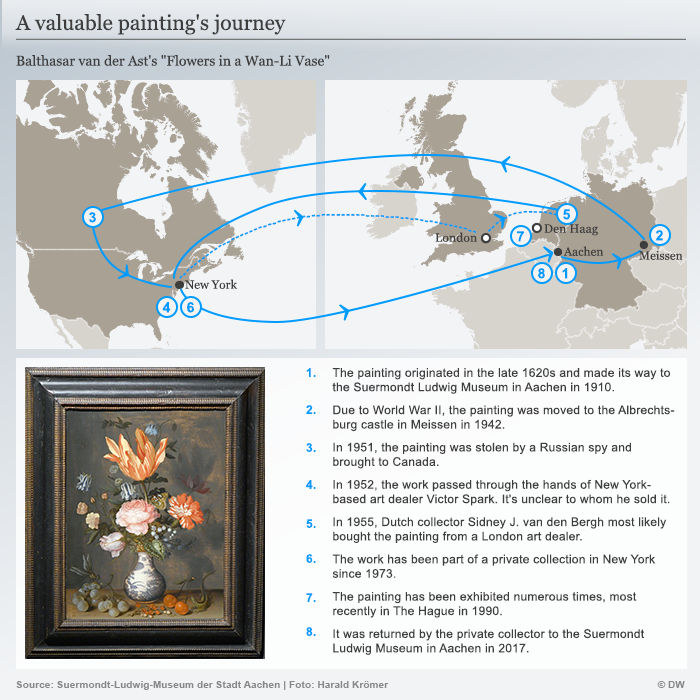

Created in the 1620s, the work became part of the Suermondt Ludwig Museum collection in 1910.

Looted by a Russian spy

During World War II, many art collections were put into storage to protect them from the bombings. Van der Ast's work was brought together with other paintings to a large art depot at the Albrechtsburg castle in Meissen in eastern Germany.

After the war, the Soviet occupiers confiscated the works, but "Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase" and 12 other paintings from museums in Aachen and Dresden were not among them.

Instead, a certain Alice Tittel from Meissen, later known as Alice Siano, had already helped herself to the valuable art. "It wasn't looted by the Nazis, (…) but was literally stolen," explained van den Brink.

It wasn't until 2005 that it became known that Alice Siano was a spy working for the Soviet Union.

She took the artworks to West Berlin, where she came into contact with American troops. In 1951, she received a visa for the US and Canada. Customs documents for the 12 paintings in her possession have been recovered, though they don't mention the van der Ast work. "It would have been too expensive to pay official customs duties," explained van den Brink.

Paintings without provenance

In 1954, the Canadian public prosecutor looked into the case after a tip-off that a theft had occurred. Alice Siano showed the authorities her export and import permits. The paintings were supposedly to be exhibited at the Gallery of Fine arts in Windsor, Ontario, which the museum director confirmed.

But he was apparently in on it, since he maintained that the paintings were not valuable. The van der Ast was sold to a New York dealer within three months.

"Alice Siano couldn't sell it herself because she wasn't registered as the owner of the smuggled painting," explained van den Brink. But for a museum director, it wasn't difficult to sell paintings at the time.

"Many museums have works in their collections without provenance records. We have that here in Aachen too," according to van den Brink. These works are referred to as "old inventory." "The items were given as gifts or the old documents simply don't exist anymore.

A missing fly or the real thing?

Peter van den Brink (center) and Fred G.Meijer (right) contributed to solving the mystery behind the van der Ast painting

In the van der Ast case, the deception went even further. In 1955, a painting surfaced that was strikingly similar to "Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase." The Dutch art collector Sidney van den Bergh exhibited the work in The Hague. The exhibition catalogue explained that the painting varied slightly from the disappeared work from Aachen - a fly was missing from the upper left corner.

Thought to be a copy with slight variations, that work became part of a private collection in New York in 1973. It wasn't until 1997 that it was found to indeed be the original missing van der Ast, thanks to Fred G. Meijer from the Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD).

"We later confirmed it by comparing details," said Meijer. "The paint was so thin in some places that the grain of the wood beneath it could be seen." Due to the visible grain, it was determined that the two paintings were in fact one - and once the work was restored, the missing fly could be seen as well.

Reward for the collector

Once it was identified, it took another 20 years for the work to make its way back to Aachen. The Art Loss Register in London was able to at least roughly trace its path following the theft in Meissen. With evidence in hand, museum director van den Brink was able to go public with the story in 2008.

However, he couldn't demand the restitution of the painting, since the New York collector had purchased it "in good faith." Since the purchase had taken place in The Netherlands, it was subject to Dutch law, which stipulated that the collector could keep the work.

However, as van den Brink explained, she wouldn't have been able to keep it: "The story had been researched and published, so the collector couldn't sell. Any buyer could have purchased it 'in good faith' up until 2008." Nevertheless, the collector, who prefers to remain anonymous, received a 400,000-euro reward.

For Peter van den Brink and his team, the work is not done. Many aspects of the painting's journey are still unclear. Plus, there are two other paintings on Alice Siano's list that are still missing. Van den Brink hopes that they will turn up one day, too.