News:

Keeping the Nazi Gold

By Elliot Carter

George Patton’s Trumpian plan to fund the military after World War II.

Speaking recently about his stated desire to pull U.S. troops out of Syria, President Donald Trump repeated his frequently stated argument that the U.S. should have “kept the oil” in Iraq after the 2003 invasion. “I was always saying, ‘Keep the oil.’ We didn’t keep the oil. Who got the oil? It was ISIS got the oil—a lot of it,” he said.

The notion that the U.S. military should resort to old-fashioned plunder, seizing assets in countries it invades, is shocking in the modern political context, but there’s precedent for it. Few remember how seven decades before Trump ever dreamed up his “take the oil” scheme, Gen. George S. Patton had a strikingly similar proposal to “take the gold.” When Patton’s 3rd Army overran Nazi Germany during the Second World War, they captured vast bank holdings with an inflation adjusted 2018 value nearing $1 trillion. The brash commander suggested keeping this treasure—and actually concealing it from Congress—to create a rainy day fund for the Pentagon.

Patton first caught wind of the gold a few weeks before Adolf Hitler died by suicide, and the subsequent collapse of Nazi resistance. When American forces captured the mining town of Merkers on April 4, 1945, locals tipped them off that the Reichsbank used the old salt tunnels to shelter sensitive assets from aerial attack.

Word passed over the 3rd Army headquarters telephone at 5:05 p.m., but as Patton recalls in his diary, he decided to wait before notifying higher-ups, “as it would be stupid to claim we had found the gold reserve and then not have done so.” Meanwhile, GIs with the 90th Infantry Division were already exploring the salt tunnels in jeeps, and soon enough their headlights illuminated a tantalizing sight. One section of tunnel deep below ground had been bricked off and studded with a not-so-subtle steel vault door fit to guard Fort Knox.

The soldiers didn’t have the lock’s combination, but a shaped explosive charge did the trick. Inside they did find gold—tons of it in cloth sacks and wooden crates—as well as the looted art from across Europe and the collections of German museums.

When Patton arrived to tour the treasure with Supreme Allied Commander Dwight Eisenhower, the pair descended 2,100 feet in a rickety old mine elevator. Patton stepped out at the bottom in a jovial mode and noted that “it was very dry and the air was excellent.”

The generals were given a sneak peek at the collection of art masterpieces that would later become a plot point in the 2014 film The Monuments Men. Patton didn’t have much of an interest in the “alleged art treasures.” The gruff commander wrote in his diary that “the three that I looked at were, in my opinion, worth about $2.00 each and are of the type found formerly in bar rooms.” Patton’s mind was on the gold.

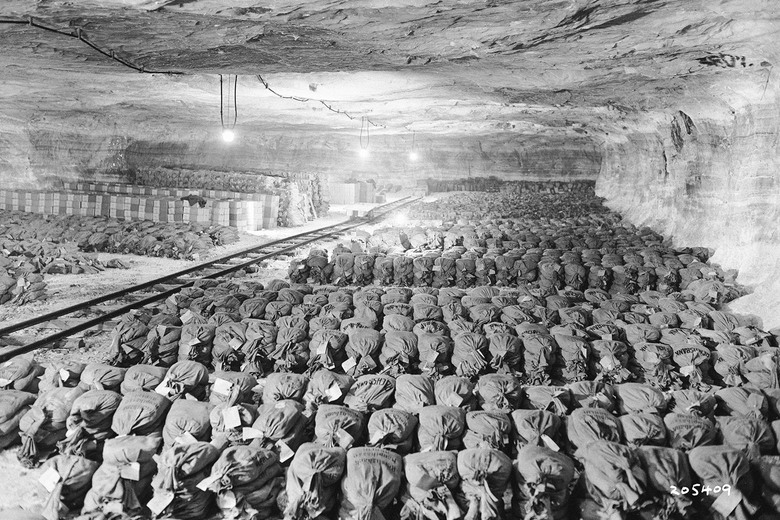

The Nazi trove did not disappoint. Inside he gleefully toured past row after row of glimmering gold bars and picked through suitcases containing thousands of gold watches, rings, and cigarette cases. The collection included far more than just Reichsbank deposits and also contained a large quantity of gold fillings wrenched from the jaws of Holocaust victims and bank reserves plundered from Nazi-occupied European nations. Capture of Germany’s Gold Reichsbank wealth, SS loot, and Berlin Museum paintings that were removed from Berlin to a salt mine vault located in Merkers, Germany. The 3rd U.S. Army discovered the gold and other treasure in April 1945.

Capture of Germany’s Gold Reichsbank wealth, SS loot, and Berlin Museum paintings that were removed from Berlin to a salt mine vault located in Merkers, Germany. The 3rd U.S. Army discovered the gold and other treasure in April 1945.

A subsequent inventory added up some “3,682 bags and cartons of Germany [paper] currency, 80 bags of foreign [paper] currency, 4,173 bags containing 8,307 gold bars, 55 boxes of gold bullion, 3,326 bags of gold coins, 63 bags of silver, 1 bag of platinum bars, 8 bags of gold rings, and 207 bags and containers of SS loot.”

That night the top Army generals sat down for dinner and discussed how to handle the discovery. Patton first suggested distributing the gold to his victorious legions, “one for every sonuvabitch in Third Army.” Failing that, the commander said it would be best to conceal the gold from the U.S. Congress and public. Gen. Omar Bradley was also in attendance at the dinner and recalled that the notion was to wait “until peacetime when military appropriations were tight and then dig it up to buy new weapons.”

This second idea may have been borne from Patton’s memories of World War I, after which Congress slashed military spending and returned the nation to a peacetime footing. The gold, either hidden away or properly invested, could transform the 3rd Army’s budget into a self-sustaining endowment, independent from the congressional appropriations process. Bradley and Eisenhower thought the idea was a joke. But Patton was deadly serious, and had already ordered a press blackout about the discovery and ringed the salt mine with tanks.

George Patton’s instinct to keep the gold fit into something of a kleptocratic pattern of behavior, according to Greg Bradsher of the National Archives and Records Administration. “A few months after discovery of the gold, counterintelligence troops found an original copy of the Nuremberg Laws against Jews” says Bradsher. “They gave it to Patton. He went home on leave and took it with him to put in a museum that he wanted to build.” The government only came to repossess immensely valuable historical documents following a National Archives inquiry in 2010.

Fortunately, a mountain of gold bars proved harder to conceal than textual records, and the real decision-makers had already set into motion a more dignified solution for the precious metals. The huge gold discovery also made it into the press despite Patton’s censors. Secretary of State Edward R Stettinius Jr. told reporters that yes the Army could hang onto the gold but only until Allied nations could agree on what to do with it.

Patton died on Dec. 21, 1945, as the result of an automobile accident, so he wasn’t able to protest the Jan. 14 transfer of precious metals to the Inter-Allied Reparation Agency. Most of the gold was eventually returned to the central banks of its countries of origin. After decades of dispute, the gold seized from Holocaust victims was donated to the Nazi persecution relief fund in 1997. As for the Army, it found ways to get by financially without a store of Nazi gold.