News:

Anne Olivier Bell obituary

By Charles Saumarez Smith

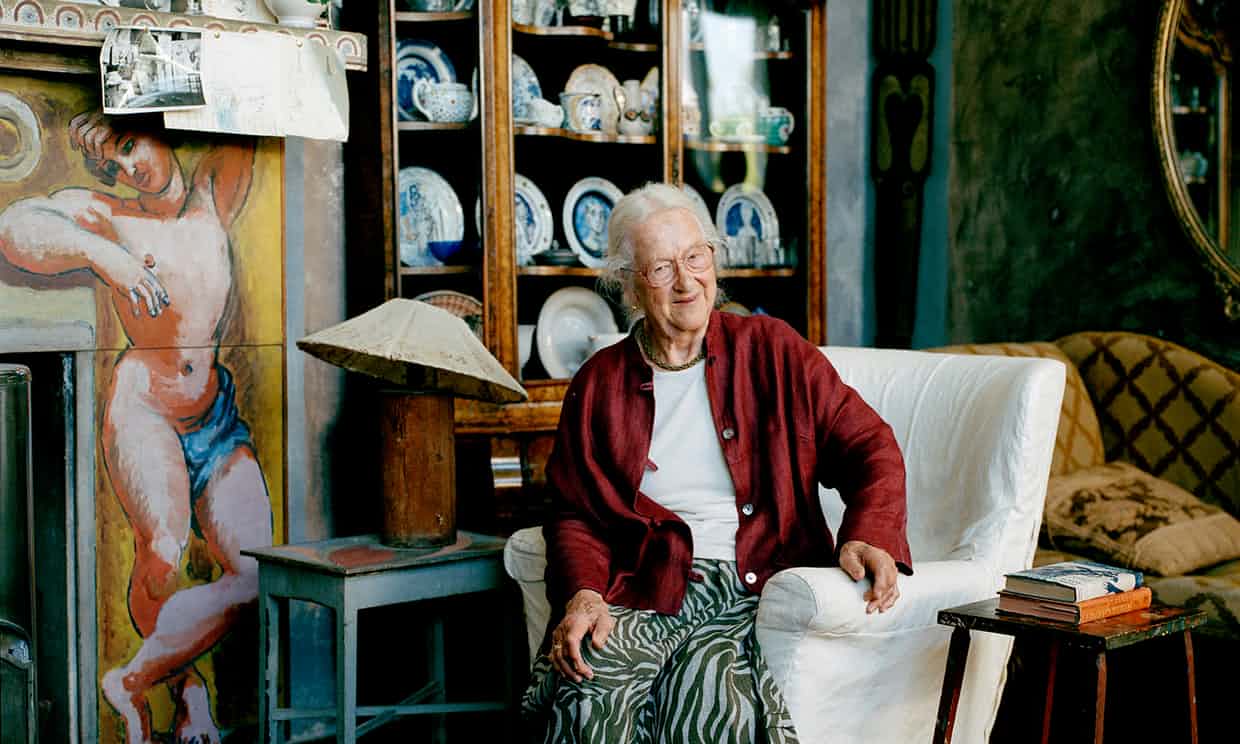

Anne Olivier Bell in the studio of Charleston farmhouse, near Lewes, the artistic home of the Bloomsbury group.

She was closely involved in the foundation of Charleston farmhouse, the home of Bloomsbury art and ideas near Lewes in East Sussex, as an independent trust in 1980, and was supportive of everyone who wanted to study Bloomsbury, exercising a fierce and critical eye over their texts.

Olivier (the name by which she was always known) was born into the heart of Bloomsbury, in central London, by virtue of being the daughter of AE (Hugh) Popham, the keeper of prints and drawings at the British Museum and an authority on the 16th-century Italian mannerist painter Parmigianino, and of Brynhild Olivier, a beauty whose father, Lord (Sydney) Olivier – uncle of the actor Laurence Olivier – was a senior civil servant and member of the Labour party and the Fabian Society.

Following her return home from Germany in 1947, Olivier joined the recently established Arts Council, where she worked on exhibitions under Gabriel White, including escorting paintings from Munich’s Alte Pinakothek on a goods trains across Germany for display at the National Gallery.

After the death of Grant in 1978, Quentin and Olivier were jointly responsible for saving Charleston farmhouse and establishing it as an independent charitable trust. Indeed, Charleston was something of a second home to Olivier, just over the hill from where they lived on the edge of the Firle estate, and she was in the front row of every event at the annual Charleston festival, correcting the occasional misstatement from speakers and audience, as well as conscientiously attending the meetings of its council and ensuring that the Bloomsbury ethos was correctly maintained.

She was educated at Marjorie Strachey’s school in Gordon Square, a vegetarian school in Hertfordshire and St Paul’s girls’ school in west London, before being sent to Germany to learn to be an opera singer. This failed, as did her brief time at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London, after which she studied art history in the early days of the Courtauld Institute.

Olivier always retained an admiration for those art historians whom she had known and with some of whom she had worked in the 1940s, including Kenneth Clark and Anthony Blunt. However, she was not a conventional art historian and was at least as interested in contemporary art, being introduced to two young painters, William Coldstream and Graham Bell, during a study trip to Paris in 1937. She had an affair with the latter, a South African painter with whom she lived until he was killed in an accident in August 1943, and who painted her in a characteristically dry style in a work, Miss Anne Popham, that was bought in 1944 by the Tate.

During the war Olivier joined the Ministry of Information as a research assistant, in the photographs and then the publications divisions, where she produced booklets on the British war effort. In 1945 she transferred to the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Branch of the Control Commission for Germany. She became one of the so-called Monuments Men, the distinguished group of archaeologists and art historians who prevented further damage to historical monuments in Germany and returned to their owners works of art seized by the Nazis. (She attended the UK premiere of George Clooney’s film on the subject in 2014.) Her diary of the time is preserved in the Imperial War Museum. She was unpopular with her fellow British officers for being willing to talk to, and even occasionally dine with, Germans who could supply her with necessary information.

In 1950, Olivier met the painter Vanessa Bell, whom she had first encountered in Paris in 1937, when Vanessa was in deep mourning for the death of her elder son, Julian Bell. Vanessa invited her to Sussex to sit for a painting. Two years later she married Vanessa’s younger son, Quentin, who had recently taken up a post as a lecturer in art education at King’s College, Newcastle, then part of Durham University. As was normal for women of her generation, she gave up her career and became, as Duncan Grant, the Scottish painter and Bloomsbury group member, described her, “an exemplary housewife”. Indeed, she had a great capacity for creating a warm and civilised domestic atmosphere, living in her kitchen where she would do the cooking and Quentin would supply the so-called “Bell booze”, a mixture of gin and ginger beer.

As a result of her marriage to Quentin, Olivier moved into the heartland of the Bloomsbury milieu and, having inherited its values, became one of the most vigorous (and vigilant) guardians and promoters of the Bloomsbury revival. A brilliant and conscientious editor, she first helped Quentin with the research for his pioneering biography of Woolf, and later applied her encyclopedic knowledge of all aspects of Bloomsbury to the editing of five volumes of her Diaries, published between 1977 and 1984. She described her work in Editing Virginia Woolf’s Diary, a small, privately printed publication, and was awarded honorary degrees by the universities of York and Sussex.

As a person, Olivier could be quietly formidable. In 1975 she was described by Sylvia Townsend Warner in a letter to David Garnett as “very handsome and stately ... She sat upright, well back into her chair – not a fidget in her ... I liked her very much, and felt she had been composed by Gluck.” There was, indeed, something magnificently stately about her, firm in her intellectual and moral values, friendly to those she wanted to be, and occasionally a touch contemptuous of those she thought too interested in money.

In December 2007, when she was honoured by the American government as one of the Monuments Men, she spoke with dry humility at a ceremony at the US embassy. Not long afterwards she was diagnosed with a brain tumour, which turned out to be only a minor stroke. She was appointed MBE in 2014.

Quentin died in 1996. Olivier is survived by a son, Julian, and two daughters, Virginia and Cressida, six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren•

Anne Olivier Popham Bell, art scholar, born 22 June 1916; died 18 July 2018