News:

20 Years On, It’s Time to Admit Our Rules for Handling Nazi-Looted Art Have Failed

By Noah Charney

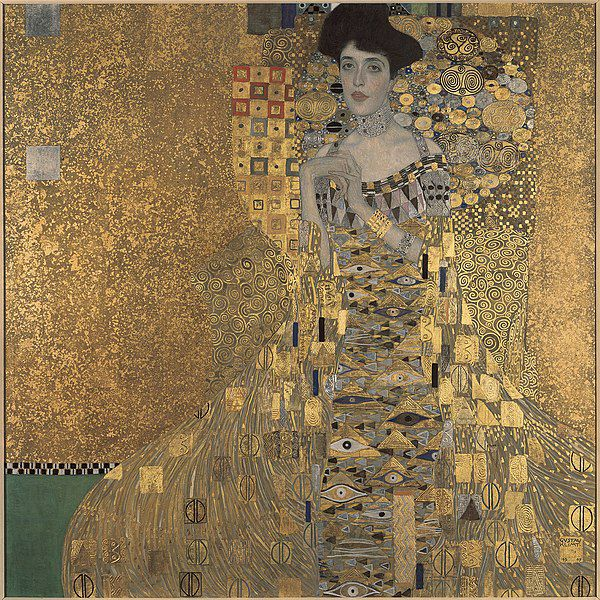

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I, 1907, which was involved in one of the most high-profile and protracted restitution disputes.

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer I, 1907, which was involved in one of the most high-profile and protracted restitution disputes.

On December 3, 1998, 44 world governments and 13 international NGOs came together in Washington D.C. to develop a guide for dealing with Nazi-looted art. Called “The Washington Principles,” primarily written by American diplomat Stuart Eizenstat, they outlined 11 suggested rules that advocated for, among other things, a concerted effort to identify work that had been confiscated, the opening of records to assist in this process and the establishment of a database to store the information found. On November 26-18, a conference in Berlin marking the 20th anniversary of these goals will assess the success of these objectives.

But it seems like there are some tough conversations to be had. “The Washington Principles have been a failure, and the conference is an attempt to whitewash this failure,” said Marc Masurovsky, one of three cofounders of H.A.R.P. (Holocaust Art Research Project), which was established in 1997, one year before the Washington Principles were pronounced. The problem is that, according to Masurovsky, the Washington Principles look and sound good, but have been almost completely ineffectual.

Provenance research is a very sticky wicket; Masurovsky describes it as “a toxic field of study.” Provenance is the documented history of an object, the story of the many hands through which it has passed. The issue becomes problematic when research into an artwork’s history overturns stones that cover dark recesses of a nation’s past. The simple research into an object’s “biography” then becomes a political issue, for instance with Switzerland’s resistance to repatriating compelling claims by Jewish families whose art was seized during the Second World War (though one could replace Switzerland with just about any European country). This can make provenance research a matter of individual scholars or families pitted against nations that would rather not hear about World War matters anymore. Reclaiming one’s looted art can feel like a Sisyphean task. Masurovsky and his colleagues try to help, but it’s always a struggle.

By some estimates, around five million cultural heritage objects changed hands inappropriately during World War II alone, and that doesn’t count the decade leading up to it, when the Nazis were forcibly seizing works of art from their countrymen. Masurovsky considers most estimates published by governments about the number of artworks stolen to be gross underestimates, and argues quite reasonably that there has been far too much focus on museum-quality masterpieces. Of course there were tens of thousands of these, including the some 7,000 that were destined for Hitler’s planned super museum in Linz, Austria, and which were hidden in a salt mine in the Austrian Alps. They were only narrowly rescued from destruction by a team of Austrian miners working with the Resistance, four Austrian double agent commandos and several of the Monuments Men, (as touched on in my book Stealing the Mystic Lamb, and partly dramatized in the George Clooney film, Monuments Men).

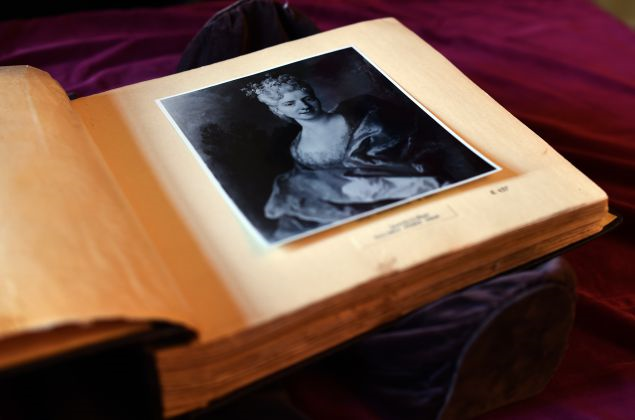

The last known leather-bound Hitler Album, created by a Nazi task force documenting stolen work, at the National Archives in Washington, DC

The last known leather-bound Hitler Album, created by a Nazi task force documenting stolen work, at the National Archives in Washington, DC

The sex appeal of headliner masterpieces that were indeed stolen and dramatically recovered (or never recovered and still missing), has led to a certain amount of overshadowing of the millions of objects by significant, but less famous, artists. Masurovsky mentions the likes of Nussbaum and Soutine among the hundreds of Jewish artist who are marginalized, primarily because they were Jewish, even if they were artists of the highest quality.

Masurovsky’s initial goal in founding H.A.R.P. was to raise awareness about issues in restitution, primarily by focusing on archive-trawling research, in order to piece together the ownership histories of objects that changed hands during the Nazi era. But he has also become an activist, much against his will, speaking out on restitution issues as a public figure, usually regarding cases where those trying to recover stolen works are struggling to find supporters for their cause.

Restitution cases saw a huge uptick with the onset of the internet era, for the simple reason that people, for the first time, could easily find out where objects were located through a simple google search. In earlier years, cases only came up when survivors or their descendents stumbled across a work entirely by accident. And while of course most of the thefts were on the part of the Nazis, one of the cofounders of H.A.R.P. actually began by specializing in cases in which Allies, while serving in Europe, had quick fingers and took art back home as a souvenir or trophy.

These days, what sounds at first like a straightforward case in which an object should be returned becomes complicated quickly. Most instances feature individuals or families against major institutions like museums or nations. Deaccessioning a work, particularly from a national collection, is vastly complicated, slow and bureaucratic, even under the best of circumstances and with good will and desire on all parts. But when the new owners are resistant, it can be like wading through a tar pit.

It is also more difficult to find lawyers to help, since such cases rarely involve cash reparations and winnings, so legal aids don’t have the same financial incentive to throw themselves into the fray. But just imagine a family of normal middle-class income faced with taking on, say, a national gallery in Austria, in order to claim a painting that was once owned by their ancestor. The cards are stacked wildly in favor of such megalithic institutions, with extensive boards of trustees and staff lawyers and sometimes ministries backing them up. It is daunting, to say the least, and in the last 20 years since the Washington Principles were instituted, most potential claimants have given up in the early stages, scared by the prospects.

H.A.R.P. put their names on the map in 2017 by pointing out to the district attorney’s office of New York the fact that two paintings by Egon Schiele, on loan from Austria, had questionable backgrounds and yet were sent to MoMA in New York for display in an exhibition. After H.A.R.P. sounded the alarm, the district attorney determined that it would hear a case for the restitution of these two paintings to two separate Jewish families that claimed that they had been taken from them. The seizure of the paintings in that case led directly to Austria implementing a new law on restitution, the first European country to do so. Masurovsky says, with a sigh, that it seems that a fight must be undertaken in the courtrooms for anyone to pay attention and make changes.

The very fact that the courtroom seems to be the only place that prompts useful action is proof enough that the Washington Principles, while well-meaning, have been ineffectual.

Francesco Guardi’s A View of the Piazzetta Looking Towards San Giorgio Maggiore, a painting looted by the Nazis during World War II, retrieved by the Monuments Men.

Francesco Guardi’s A View of the Piazzetta Looking Towards San Giorgio Maggiore, a painting looted by the Nazis during World War II, retrieved by the Monuments Men.

The Washington Principles were officially published on 3 December 1998. The 11 guidelines they contained were “non-binding principles,” which is to say that they were merely suggestions. While clearly well-meaning, they appear to have a great deal of weight and pomp, but experts in the field tend to agree, they don’t really do anything, and so are not useful to claimants. Masurovsky, in his blog, Plundered Art, offers suggestions that would update them, but he is wary of the conference scheduled in Berlin. He anticipates much patting on the shoulders and self-congratulations for something has had almost no actual positive effect.

Masurovsky cites numerous high-profile cases in which major museums, often backed by their nations, refused to return objects that were demonstrably looted. It is ironic, for instance, that the Brera Museum in Milan refuses to return a painting from the Gentile collection, when the nation of Italy has repeatedly and successfully demanded the restitution of ancient artworks looted from its territory. Yet, if they possess a painting that was demonstrably looted from a Jewish family, they don’t want to hear about returning it. This is a point that even the former Advocate General of Italy, Maurizio Fiorilli, agreed with when he met with me and Masurovsky at the recent ARCA Conference on the Study of Art Crime, held every summer in Italy. Sometimes even nations that we think of as intending the best for their citizens have dug their heels in. Masurovsky says that Switzerland only last year organized the restitution of a war-looted artwork, making it seven decades after the fact, and with numerous other possible objects not restituted (or at least, not yet).

And things are not looking up. The Netherlands has recently changed the rules for restituting looted art, stating that they will consider restitutions from museums if removing the questioned object would not interfere with the museum’s didactic program. This gives museums a “Get Out of Jail Free Card,” refusing reasonable restitution claims on the grounds that it will “mess up” their exhibition layout.

The most difficult element that Masurovsky sees as a stumbling block in legitimate restitutions is current owners hiding behind the claim of “good faith purchases.” According to current law, one only must be able to demonstrate that you genuinely thought an object was legitimate when you acquired it to get out of returning the object in question or suffering any legal damages. One can imagine that it is relatively easy to claim good faith, even if one’s faith was not good. This has been the undoing of many cases. But for the cases where claimants persevered, Masurovsky and his colleagues have often been there, behind the scenes and sometimes at the fore, traveling the world to speak about the issues involved in this cause, occasionally appearing in courtrooms, and talking about the dangers of provenance research.

Why dangerous? “Because provenance has become a political tool,” he said. Attempting to research provenance means looking into the often unseemly past of nations, and sometimes their heroes, whether they are museums or politicians and art world protagonists. Does America really want to learn that some of their so-called “Monuments Men,” who have been so glorified for their efforts to save Europe’s art treasures, may have also pocketed some of them? Does Germany want to uncover still more unseemly tales of its recent history? Does amiable Switzerland want to hear in the courts of some of its less-amiable activities or oversights from decades past? These are things that people and even nations feel like they would often rather forget, but when the cost of keeping them locked up means that some might never have their rightful property returned to them, it’s too high.