News:

New York City museums are fighting to keep art stolen by the Nazis

By Isabel Vincent

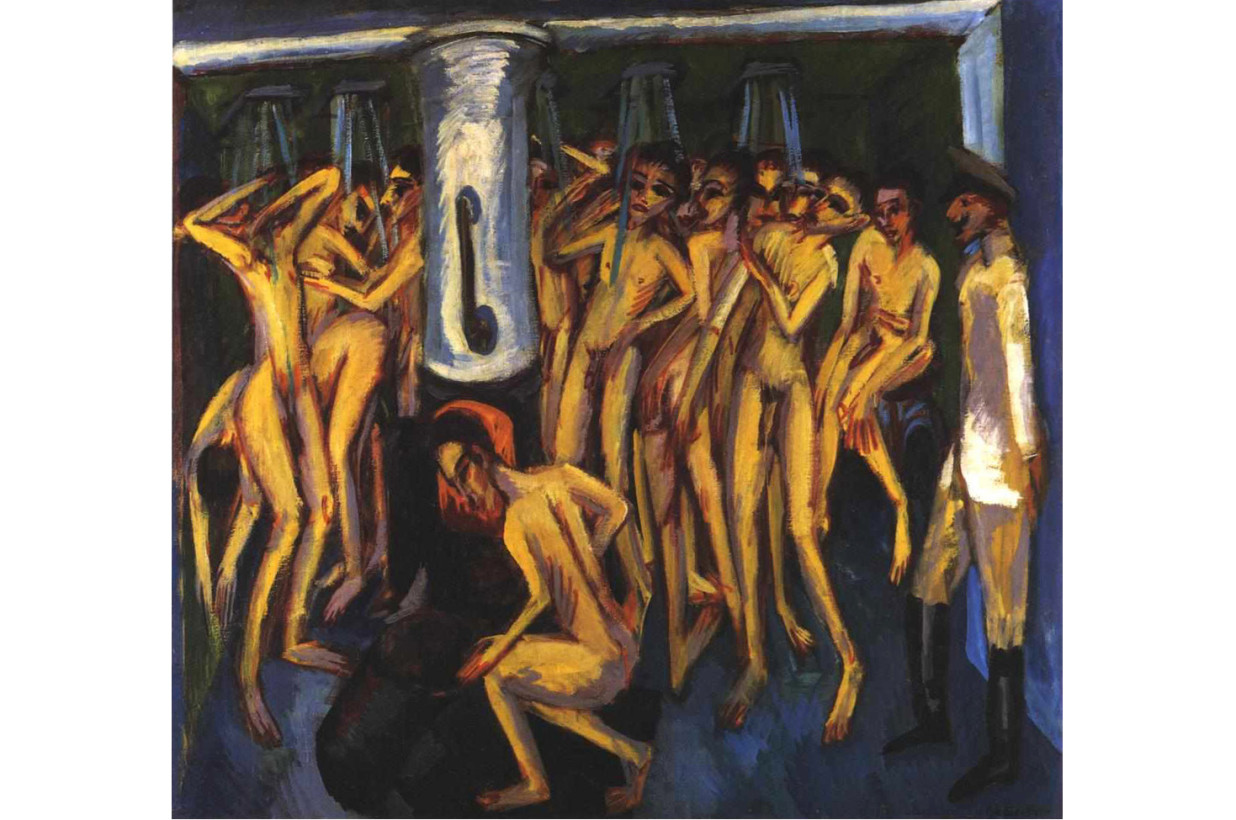

The 1915 painting “Artillerymen” depicts a group of nude soldiers in a shower — a powerful statement on the dehumanization of war. And the story behind the painting also speaks to a shocking racket that still plagues many New York museums today.

Stolen by the Nazis from the family of German Jewish art dealer Alfred Flechtheim, who was forced to flee Berlin in 1933 after Adolf Hitler came to power, the painting has hung on the walls of Manhattan art galleries for more than 60 years.

In October, the Guggenheim finally returned “Artillerymen” to Flechtheim’s surviving family members in the US, and his heirs praised the museum for righting a historical wrong.

“I am grateful to the Guggenheim Foundation for doing the right thing,” said Michael Hulton, Flechtheim’s great-nephew and heir in a recent statement. “Overall, restitution is about recognition and paying respect to the suffering of the Nazi victims’ families.”

But “Artillerymen” is the exception among New York City museums, where scores of Nazi-looted works can be found proudly on display. “It’s a real miscarriage of justice,” said an attorney who did not want to be named because he is arguing Nazi-looted-art cases in federal court.

Lawyers are appealing a federal judge’s refusal to return Picasso’s “The Actor” (above left) — one of the Met’s most valuable paintings — to its heirs. Auguste Renoir’s “Portrait of Tilla Durieux” (above right) was sold by its owners fleeing the Nazis in 1935 and it also now hangs at the Met.

There are “tens of thousands” of artworks in US museums with Nazi-era provenance, according to art historian James Cuno speaking before Congress on behalf of museum directors in 2006. Of those, thousands are in New York City museums, experts say. And no one really knows how many have been returned to their rightful heirs.

Between 1933 and 1945, the Nazis seized an estimated 650,000 works of art — the largest art theft in world history. They took them from Jewish families and grabbed so-called “degenerate” works — including pieces by Picasso, Matisse, Chagall and van Gogh — off the walls of German museums. Some of the plundered paintings were destroyed, but others were sold abroad with the cash going back to the Nazi war machine. By the end of the war, a great deal of the art was scattered around the world.

“There is no full listing of artworks that have been returned to the heirs,” said Wesley Fisher, director of research at the World Jewish Restitution Organization’s Looted Art and Cultural Property Initiative. “There’s no transparency on that number.”

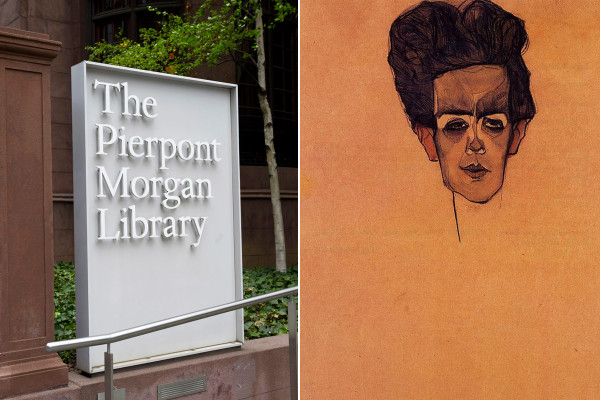

Heirs of Viennese cabaret artist Fritz Grunbaum say that Egon Schiele’s “Self Portrait,” now at the Morgan Library, is among the works stolen by the Nazis.

“Artillerymen,” by German expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, ended up in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art after WWII and was given to the Guggenheim in 1988 in an exchange of paintings, according to the Guggenheim.

The return of “Artillerymen” likely took decades because the restitution of Nazi-looted art didn’t gain urgency until the 1990s. Immediately following the war, saving lives was the priority, not the return of art, Fisher told The Post. Also, archives closed after the war made provenance research extremely difficult, he said.

Then, in 1998, 44 countries and hundreds of museums agreed to uphold a set of principles about identifying art looted by the Nazis. The signatories to the so-called Washington Principles called for a “just and fair solution” to be reached if prewar owners came forward to reclaim their family’s legacy. Museums further pledged to conduct thorough research into their acquisitions with dubious Nazi-era provenance.

In 2016, Congress passed a law — Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act — that resets the statute of limitations on recovering Nazi-looted art from galleries and museums. In the past, museums were able to use statute of limitations against claimants, saying they had waited too long to sue. But now, anyone bringing forward a new claim has six years to litigate it.

On Monday, hundreds of museum directors, art experts and politicians will assemble in Berlin at a three-day global conference to assess just how effectively museums and art galleries have returned Nazi-looted art over the past 20 years.

While the Guggenheim recently made headlines by returning the Kirchner painting, other city museums have fought the heirs in federal court and won.

In February, the heirs of a German Jewish businessman who was forced to flee the Nazis lost their suit against the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the return of Pablo Picasso’s “The Actor.” The painting was owned by Paul Leffmann who sold it under duress for $13,200 to a Paris dealer when the family fled Cologne in 1938. It is now worth an estimated $100 million, said lawyers for the estate.

“The Leffmanns would not have disposed of this seminal work at that time, but for the Nazi and fascist persecution to which they had been, and without doubt would continue to be, subjected,” according to court papers.

The lawyers for the Leffmann heirs are appealing the federal court’s decision.

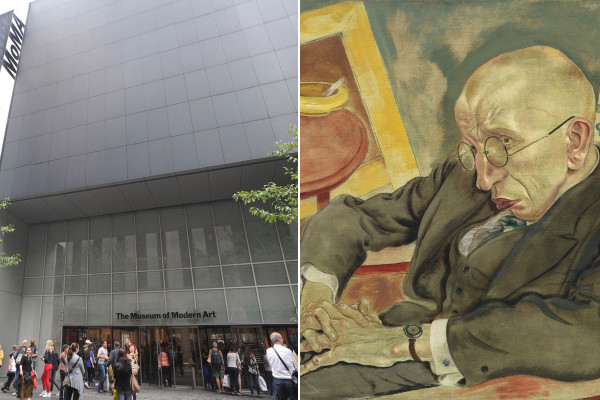

Descendents of German painter George Grosz lost their battle against MoMA for the return of Grosz’s 1927 work “The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse.”

“Clearly, we are disappointed,” said the family’s attorney Lawrence Kaye, who specializes in art-restitution cases. “Based on our experience, we feel that many US courts are not following the Washington Principles.”

Another contentious painting at the Met is Auguste Renoir’s “Portrait of Tilla Durieux,” which the artist painted in 1914 while confined to a wheelchair.

“The painting is one of the jewels of the Metropolitan Museum,” said Jonathan Petropoulos, professor of European History at Claremont McKenna College and a leading expert on Nazi-looted art.

Durieux, a famous Berlin actress, took the painting with her when she fled Nazi Germany for Yugoslavia with her German-Jewish husband Ludwig Katzenellebogen in 1933.

The couple’s heirs have said that they sold the painting under duress in 1935. Katzenellebogen was arrested in April 1941, transported to Berlin and murdered in 1943. The painting found its way to Paris and later to New York, where it was donated to the museum in 1960.

The heirs of German painter George Grosz tried to get three of his works back from the Museum of Modern Art but said the gallery played dirty, trouncing them on a legal technicality, saying the family filed their 2009 claim too late for “The Poet Max Herrmann-Neisse,” painted by the artist, who was virulently anti-Nazi, in 1927. Grosz fled Germany in 1933, accepting a teaching position with the Art Students League in New York.

Grosz’s heirs argued in court papers that the Hermann-Neisse portrait was confiscated in 1933 and reappeared in 1952 when it was bought by the museum for $850 from Charlotte Weidler, a German immigrant who falsely claimed to have inherited the painting.

“I Love Antitheses” (above right), by painter Egon Schiele, belonged to a man killed at Dachau concentration camp. Rightful ownership of Schiele works at the Neue Galerie (above) and other museums is disputed.

Other paintings scattered throughout New York museums by the Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele are also under a cloud.

The provenance of works by the artist at the Neue Galerie, The Morgan Library and MoMA that were in the estate of Austrian Jewish cabaret artist Fritz Grunbaum is currently being challenged in court. Grunbaum, an avid collector of Schiele, a protégé of artist Gustav Klimt, died at the Dachau concentration camp in 1941. His wife, Elisabeth, was forced to surrender the family’s art collection to the Nazis before her transfer to a death camp in 1942.

Recently, under pressure from high-end art dealers in London and New York, Germany’s Lost Art database, which catalogs Holocaust victims’ claims of Nazi-looted art, erased the 63 Schiele paintings under dispute. Among them were the paintings in New York galleries.

Grunbaum’s estate is fighting back. Tim Reif, his Washington-based grand-nephew, says his family has been trying to reclaim Grunbaum’s collection since the 1950s.

“This has been going on since I was in the single digits,” said Reif, now 59. “It would be the smallest measure of dignity to return these paintings in his name.”

On Monday at the Berlin conference, Grunbaum’s heirs say they will demand that the US State Department seeks justice and pressures Germany to restore Schiele’s art to the database of stolen works.

“Seventy years is far too long to wait,” said Reif, a lawyer.

“This is an injustice that museums and collectors know how to correct, and they need to do it now.”