News:

Were Your Family's Books Stolen by the Nazis? New Online Initiative Might Help You Find Them

By Ofer Aderet

The Nazis looted millions of books from Jewish families during the Holocaust. German libraries’ online databases are helping put the situation right

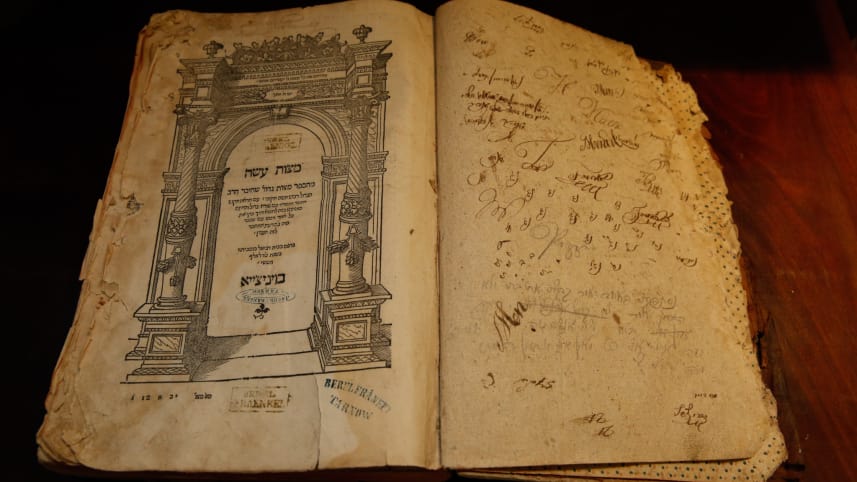

A book returned to the Schor family, January 2019

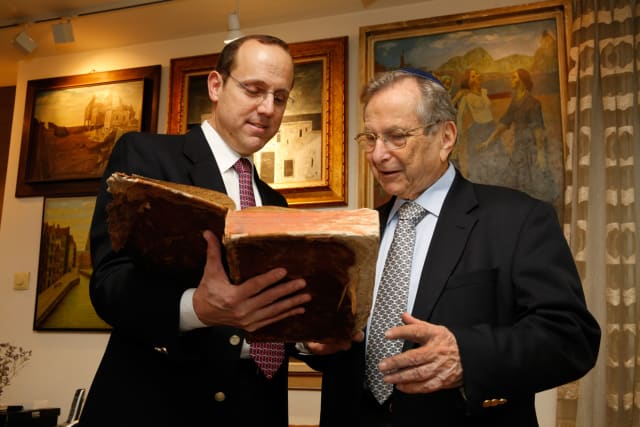

A year ago, Berl and David Schor returned from Berlin to Modi’in with a real treasure. Berl, the 91-year-old father and his 52-year-old son David, returned home with an almost 500-year-old book stolen by the Nazis from their family in Poland.

This restitution was made possible by an initiative by German libraries, which set up an online database letting the heirs of books looted by the Nazis find their lost property.

Over the past 15 years, about 15,000 such books stolen during the Holocaust have been returned to families and organizations in Israel, the United States and Europe by German libraries.

Other looted books have been found outside Germany; for example, in 2015, the library of the Vienna University of Economics and Business returned 700 books stolen from a man named Leopold Singer.

Researchers in Germany estimate that most large German libraries contain books looted by the Nazis from Jews. One-third of the 3.5 million books in the Berlin Central and Regional Library are thought to have been stolen by the Nazis. Since the library began examining the source of the books, some 900 books have been returned to their owners in 20 countries.

It’s very difficult to recover looted property,” David Schor, an attorney, told Haaretz this week.

Locating the stolen property is just one stage on a long road; just as complicated is locating the heirs. In many cases no legal heirs exist because entire families were murdered during the Holocaust and left no survivors. In other cases, the potential heirs don’t even know of the existence of the books, or that they’re in German libraries.

The online databases came in handy for the Schors. One stolen book of theirs, a copy of “Sefer Mitzvot Gadol” (“The Great Book of Commandments”), describes the 613 commandments in Jewish law. It was written in around 1250 by Rabbi Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, France.

Daniel Lipson, a librarian at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, found that early versions of the “SeMaG,” as the book is known by its Hebrew acronym, were printed in the late 15th century. Lipson believes the book “is one of the first Jewish books ever published.” The family’s copy was printed in Venice in 1546.

The tome’s fate is a fascinating story in its own right. Before World War II, the Schors’ library contained books on the Torah and Jewish law that were hundreds of years old, including thousands of volumes from printing’s first days, Schor said. Berl and David Schor with their returned copy of the “Sefer Mitzvot Gadol,” Modi'in, January 2019

Berl and David Schor with their returned copy of the “Sefer Mitzvot Gadol,” Modi'in, January 2019

The library was kept in the home of David’s grandparents, his father Berl’s parents, Majer and Mila Schor in Krakow, Poland. Because they had Turkish passports, at the beginning of the war they could stay reasonably safe because Turkey was a neutral country.

When the war started on September 1, 1939, the 12-year-old Berl was sent by his family to Lithuania, where he obtained a transit visa from the Japanese vice consul in Lithuania, Chiune Sugihara. The diplomat was later declared a member of the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for saving around 6,000 Jews who fled the Nazis.

After a long journey that included travel through Russia, China and Japan, Berl reached safety in New Zealand.

Helped by a Pole

Before 1942, when the parents’ passports were about to expire, the Turkish consul in Berlin refused to renew them and reported on the parents to the Gestapo. An officer in the Polish police of the Nazi occupied General Government, who knew the Schors, warned them, so they went into hiding. Majer Schor also wanted to save his library. A Polish friend, Prof. Tadeusz Kowalski of the Jagiellonian University of Krakow, agreed to store the family’s books in the university’s basement.

The books for the most part were treated well, but not Majer and Mila Schor. After seven months of hiding, they were arrested when they tried to escape Krakow in a car. They were sent to the Plaszow concentration camp just outside the city and were murdered there by the camp’s notorious commandant, Amon Goeth, in July 1943.

At the end of the war, their relatives renewed contact with Kowalski, who returned the books to the family in New Zealand. He refused to accept money, and when the family insisted on compensating him, he asked to keep a single book for himself: a first edition of a Jewish prayer book edited by Rabbi Isaiah ben Abraham Horowitz. The rabbi, better known as the Holy Shelah, was born in Prague and died in 1630 in Tiberias.

This specific book had great sentimental value because it bore the signatures and stamps of many generations of the family,” David Schor said. “But if it were not for Prof. Kowalski, the entire library would have been lost.”

Still, the family discovered that many books were missing. “The circumstances of the disappearance aren’t known,” Schor said. “It’s possible that they were looted while they were being stored in the basement of the university in Krakow. It’s possible that the crates they were moved in after the war over land and sea to New Zealand were lost on the way.”

Kowalski died in 1948. His son donated to Yad Vashem, through Berl Schor, a scroll of the Book of Esther he found thrown out in the ruins of the Krakow Ghetto.

The Schors reclaim stolen books at the University of Potsdam library, January 2019

The Schors reclaim stolen books at the University of Potsdam library, January 2019

After the war, Berl Schor made aliyah and took his parents’ library with him. Some of the lost books were found over the years in old-book bookstores in Antwerp and New York. They were bought up and returned to the family.

The stolen “Sefer Mitzvot Gadol” somehow made its way to the University of Potsdam library in Germany. In 2014, the university launched a project to identify Nazi-looted items, and in doing so joined a number of other large libraries in Germany, including the Berlin Central and Regional Library, the Free University of Berlin library and the libraries of Hanover and Baden. The funding for the project came from the German government.

The libraries put all the information they had on the stolen books in the online Looted Cultural Assets database they had set up.

I got to this website by chance while searching for information on the internet about one of the family’s ancestors,” David Schor said. “Suddenly a picture of the book’s title page popped up, which bore the stamp of the family ancestor, which I recognized. It was a great surprise.”

Finding stamps, signatures and dedications on books is one way to prove ownership. In the case of the Schors, the stamps of eight generations were found in the “Sefer Mitzvot Gadol.”

Heavy reading

Before leaving for Germany to arrange the book’s return, Schor turned to the National Library, where other copies of the same book are preserved, to clarify how the tome looked and how much it weighed – 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds).

A few days before leaving, they realized they didn’t really know what the book looked like and how big it was, something worth taking into account when you have to identify an item or pack a suitcase to have room for it,” said Lipson of the National Library.

Lipson, too, found in the database a book that had been stolen from his family. From 1933 his great-grandfather, Dr. Karl Elias, owned a book that was published for the anniversary of the founding of B’nai B’rith. Elias’ signature is preserved in the book. Elias fled the Nazis in time and in 1937 immigrated to British Mandatory Palestine, but left the book behind. His family decided not to ask for its return.

When the Schors received their book, they discovered that a new stamp had been added; alongside the stamps of the family’s forefathers, it now carried the stamp of the University of Potsdam library. “This German stamp tells the story of the book’s wanderings, and we attribute symbolic significance to it,” David Schor said.

The family gave the German library permission to scan the book so it could be made available to students and scholars.

Jewish organizations are also helping find and return stolen books. The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, better known as the Claims Conference, and the World Jewish Restitution Organization run a database on items looted by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg. This task force was headed by the chief ideologue of the Nazi party, Alfred Rosenberg; it was established in Paris in 1940 to organize systematic looting of Jewish art and other cultural collections.

As fate would have it, the Nazi bureaucratic machinery is helping locate the organization’s looted goods. Rosenberg’s staff looted 6,000 libraries and archives all over Europe and left detailed registries of what they stole.

The Nazis looted millions of books belonging to Jews. Some they burned, but many were transferred to libraries in good condition.

They hoped to utilize the books after the war was won to study their enemies and their culture so as to protect future Nazis from the Jews who were their enemies,” Patricia Kennedy Grimsted, a senior research associate at the Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University, told The New York Times this week. She is also one of the world’s top experts on the libraries and archives stolen during World War II.

After the war, the Allies located about 3 million of these books and returned some to the countries where they were stolen from. Many books were taken as booty by the Red Army and to this day are in libraries in the countries of the former Soviet Union.

In 1945, what became the National Library was under the auspices of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. That year the university established its Treasures of the Diaspora Committee, which sent people to Europe to bring back some of the books that survived the Holocaust.

It was better to save them for Judaism in its entirety, to gather them in Jerusalem, instead of having them used and abused,” wrote the writer and librarian Avraham Yaari at the time. Yaari didn’t want to “abandon the treasures to booksellers, who will pounce on them … or to rats and worms.”

About 900,000 books arrived in Israel from Europe from the end of World War II through the ‘70s – some with the aid of the Claims Conference and most with the help of Hebrew University and the National Library. Prof. Dov Sidorsky, an expert on the fate of Jewish books under the Nazis, estimates that a third of these books have found their way to Israeli libraries. Tens of thousands are in the National Library.

The National Library documents 13,000 of these books with the letters OG (for otzarot hagolah – “treasures of the Diaspora” in Hebrew), so it’s possible to identify them. In the coming years, the National Library hopes to catalogue the rest in a similar way, to “aid Jews, in Israel or overseas, in restoring the books they owned.”