News:

One Holocaust descendant's fight for justice: 'They stole not just our land, but my family's history'

By Julie Szego

Melbourne doctor Ann Drillich is fighting the might of the Catholic church over family land in Poland, where antisemitism and populism are on the rise

Ann Drillich, who is in a legal battle in Poland over her inherited family estate.

Melbourne doctor Ann Drillich, the daughter of Polish Holocaust survivors, is a rare kind of Jew who owns a Catholic church. The brick structure, Our Lady of the Scapular, stands on Drillich’s ancestral property in the medieval town of Tarnów, near Kraków. Her late mother, Blanka Drillich née Goldman, inherited the land at the end of the second world war. Aged 18, Blanka was the sole living heir to the Goldman estate, all others perished in the town’s ghetto: she found her mother shot dead in her bed.

But Drillich has never been inside her church.

The reason: in 1987, with the help of a trusted friend of the Drillichs, the Catholic church in Poland effectively stole the land and built the house of worship on the site. The Drillichs didn’t know. Ann Drillich only learned of the theft in 2010 when, as heir, she ordered a public records search about her family’s estate.

“At first it took a while to settle in, the shock of the betrayal,” she says. “And the idea that behind the injustice is a church.

“My mother’s family was one of the most prominent in town. It was like they had stolen not just our land, but my family’s history.”

And so after the shock settled, she sued.

“How could I not?” she asks.

So began an expensive, traumatic and escalating battle that pitched this meticulous woman with a scientific sensibility against a powerful religious institution.

The church appealed. Stalled. Obstructed. Counter-sued. The Polish courts, meanwhile, delivered justice to Drillich, again and again. And yet again, in a final ruling in 2016 when three district court judges found the church had acted in “bad faith” when it acquired the “abandoned” land.

That should have been where the story ends, with Drillich, a lecturer to medical students, finally clearing the fortress of legal documents from the suburban home she shares with her family and two needy miniature schnauzers. Getting closure on a draining saga that’s stirred up traumatic memories from a childhood blighted by the legacy of the second world war.

But in Poland, closure, whether legal or historical, is hard to come by, and now, on the eve of the 80th anniversary of the Nazi invasion of Poland, Drillich is facing an extraordinary legal challenge in a case that testifies to the nation’s populist zeitgeist under the ironically-named Law and Justice party, and its fraught relationship with the past.

The Goldmans’ roots in Tarnów stretched back centuries. Before the war, their sprawling estate in Gumniska Street boasted a tile factory, extensive gardens and a neo-Gothic villa. While the latter, taken by the state in 1985, now houses a public registry and is officially named “the Wedding Palace”, the building is still known colloquially as “Goldmanowka”, Goldman House, after its former owners.

Photographs of Ann Drillich’s mother Blanka Drillich nee Goldman, and her great grandfather Izak Goldman (back image) who left the estate to Blanka after the second world war.

Photographs of Ann Drillich’s mother Blanka Drillich nee Goldman, and her great grandfather Izak Goldman (back image) who left the estate to Blanka after the second world war.

In 1941, the Nazis forced Blanka Goldman, her grandfather, aunt and parents into the ghetto. Within months all were murdered, except Blanka. Blanka told of “Polish thugs” rampaging through laneways, leading Nazis to Jews.

But many Poles resisted the Nazis and saved Jews. Among them, the Drillichs’ friends, the Poetschkes. Catholics with German roots, the Poetschkes had been renting part of the Goldman estate. Their son Jerzy was especially fond of Dr Drillich’s fair-haired mother Blanka, whose beauty had the advantage of not appearing Semitic. Blanka escaped the ghetto. For the rest of the war the Poetschkes hid her in the basement and attic of Goldman house while they lived upstairs.

It was a poignant display of bravery: had the Nazis discovered the Poetschkes’ subterfuge they would surely have been executed. In the 1990s, thanks to Drillich’s family, Jerzy was honoured as a “Righteous Pole”, a gentile who risked his life to save Jews. His name is listed on the honour roll at Warsaw’s POLIN: Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

Yet in the complex duality of Polish-Jewish relations, Jerzy’s saving Blanka’s life did not stop him conspiring with the church to steal her family’s property.

“My father said Jerzy’s betrayal was one of the biggest disappointments of his life,” Drillich says.

Tarnów’s 25,000 Jews accounted for almost half the town’s pre-war population. After liberation only about 700 returned — and according to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum virtually all of them soon left after encountering lingering antisemitism. Such was the case with Blanka. Three years after inheriting her estate, she left Poland, married Henryk Drillich, also a survivor from Tarnów and later settled in Australia. She left the Poetschkes to administer the estate under her power of attorney.

In following decades, the communist authorities confiscated much of the land.

The more painful travesty was to come.

In 1986 the Diocese Curia in Tarnów, through Bishop Piotr Bednarczyk, wrote to Henryk offering to buy the estate of Blanka, by then deceased. The parties haggled over terms without striking a final agreement. Yet that same October, on the advice of parish lawyers, Jerzy successfully applied to Tarnów’s Regional Court to gain ownership of the “abandoned” land through adverse possession.

Asked for the address of Blanka Goldman, he testified “unknown”. He’d sent a condolence card on her death 13 years earlier.

He donated half the 8,500 square metres to the church, sold the other half and pocketed the money. It was only in the 1990s that he resumed contact with the Drillichs. When in 1993 Henryk visited Tarnów for the first time since the war, Jerzy showed him round the old estate. He said nothing about the plots that went to the church. He has since died.

***

After what seemed like the final legal victory for Drillich in 2016, the church concocted new proceedings about these already-adjudicated matters and dialled up the tone. In November 2017, the parish wrote to the district prosecutor’s office in Tarnów alleging — without evidence — that Drillich, her notaries and lawyers had used “forged” documents to “unlawfully swindle compensation from the church”.

Says Drillich’s lawyer, Tomasz Krawczyk: “It’s really the most outrageous legal obstruction I’ve seen in my 15-year legal career. And the whole time they were working on the minister of justice to bring the appeal.”

In May, minister Zbigniew Ziobro — also, conveniently, the prosecutor general — enlisted in the church’s crusade by petitioning the politically-dependable supreme court judges in the Orwellian-sounding Chamber of Extraordinary Control and Public Affairs to overturn the earlier rulings in Drillich’s favour. Under controversial 2017 reforms the prosecutor general can bring an “extraordinary appeal” to annul virtually any court ruling over the past 20 years.

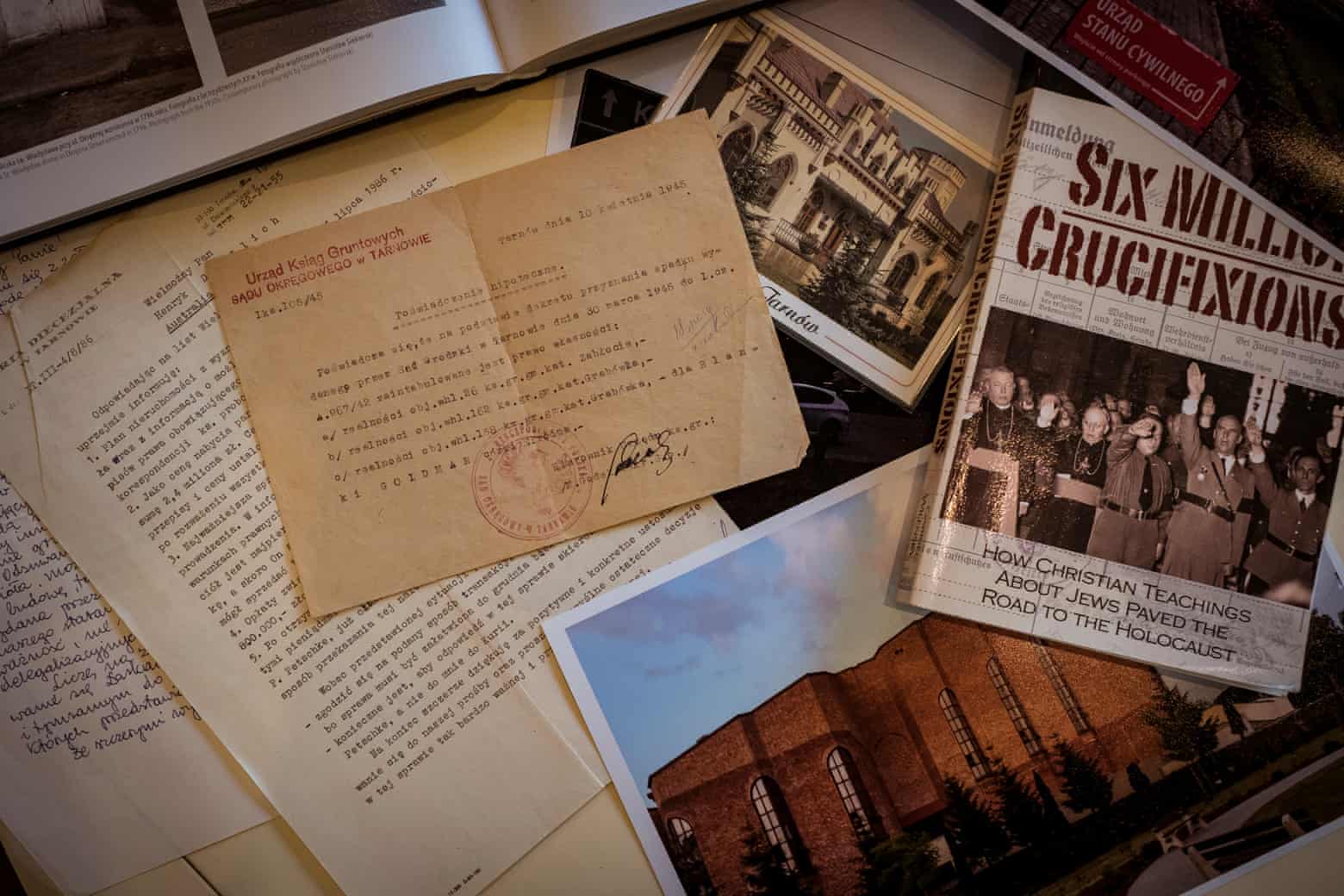

Ann Drillich’s documents, who is in a legal battle in Poland over her inherited family estate, papers and research material including images of the church in question (bottom right) and the ‘wedding house’.

The Polish president, Andrzej Duda, said the remedy, “allows the natural legal order to be restored in accordance with the principle of social justice”. The European Union sees judicial independence undermined.

“What you have to ask is why on earth would a relatively inconsequential case in a provincial town like this one be so important for the Polish government?” says Wojciech Sadurski, a law professor at the Universities of Sydney and Warsaw, and author of Poland’s Constitutional Breakdown. He notes the minister’s grounds for bringing the appeal relate to narrow questions of law, “too trivial and technical, it seems to me, to qualify as a matter of ‘social justice’. So the answer is the case is important for the church — and the politicians need the support of the church to stay in power. I think it’s as simple as that.”

Sadurski can himself testify to the prevailing enthusiasm for politically-motivated law suits; he’s fighting a criminal case and two civil suits for defamation for tweets critical of the ruling party and neutered public broadcaster. To be fair, his is a non-exclusive club. Free speech is a fragile thing in contemporary Poland. And that’s especially true when the talk is about its wartime past. Accusing “the Polish nation” of complicity in the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities attracts civil penalties — and that was a backdown from the government under pressure from the US and Israel. The original 2018 law sought to jail offenders.

Six million Poles were murdered during World War II, three million of them Jews — nearly half of all the Jews killed in the Holocaust. Scholars see in the laws an attempt to whitewash the role of Poles in the Jewish genocide and substitute a nationalist fairytale in which victims cannot also be perpetrators. Ironically, that proposition is most powerfully and unwittingly debunked in the speech — conspicuously free — of nationalists themselves. In the same month the justice minister intervened in Drillich’s case, thousands of nativists rallied in Warsaw against a US law requiring that Congress be informed about the progress of countries including Poland on restitution of Jewish assets seized during the second world war and its aftermath.

The ruling party, says Holocaust historian Jan Grabowski, of the University of Ottawa in Canada “has created a wave of fear, paranoia and anger about the so-called Jewish threat.

“Drillich’s is a very intriguing and interesting case that can have much larger ramifications than its immediate vicinity. It is part and parcel of a larger campaign to elevate the myth, the fantasy, of national innocence.”

By meddling in Drillich’s case, Grabowski says, the government “can kill several birds with one stone”.

France 24 reported protestors wearing T-shirts reading “death to the enemies of the fatherland”. One man wore a shirt saying, “I will not apologise for Jedwabne” — a massacre of Jews by their Polish neighbours in 1941 under the German occupation.

Polish nationalists argue that Poland, which did not capitulate to the Nazis — a fact many Holocaust scholars agree should be better known — has not been adequately compensated by Germany. In short, restitution is a loaded issue; one the government is keen to weaponise.

Enter Drillich. Through Drillich’s case, says Grabowski, the Holocaust historian, “the government wants to prove to the Polish nationalist electorate that the Jews are coming back to claim their properties.”

Drillich, meanwhile, pleads her cause near and far. She’s lobbied foreign minister Marise Payne (who said the government wouldn’t intervene in a private legal matter) and treasurer Josh Frydenberg, himself a descendent of Holocaust survivors, to take up her case with Polish authorities. Through intermediaries, she’s asked senior Catholics in Australia to intervene with their counterparts in Poland. (“It’s a matter of canon law,” was one perfunctory response.)

Ann Drillich, who is in a legal battle in Poland over her inherited family estate.

In July she wrote to the Vatican’s representative in Poland, Archbishop Salvatore Pennacchio:

“My family has been defamed in the Polish media and subjected to antisemitic abuse on social media, which includes tropes such as ‘blood suckers and non-believers’,” Drillich wrote. “This year in his denunciation of antisemitism, Pope Francis stated that antisemitism in all its forms is ‘completely contrary to Christian principles and every vision worthy of the human person’.

“What does it mean that faithful parishioners pray on my stolen land and that I receive abuse?”

This week she’s pinning her hopes on the extra scrutiny that will fall on Poland as world leaders prepare to descend on Warsaw for the 1 September commemoration.

The question of what she’d do if she won her claim seems almost incidental. “If I won, I’d want an apology, I’d want compensation and genuine reconciliation. I would not be looking to demolish the church.”

If she had her time again, would she still pursue justice, given she’s clocked up roughly $100,000 in legal fees? Given everything? Drillich hesitates only briefly. “The very night my mother’s grandfather was evicted (from the estate) by the Germans he slept on the balcony. He was 80-something. It was November. You can imagine how freezing it was.”

As for Blanka, freedom and a new life in Australia, did not bring lasting peace. “My mother had this real spark. Then she developed depression and I watched her go silent.”

In a tragic, distorted echo of what Blanka encountered during the war, when Drillich was 13 she came home from school one day to find her mother had killed herself. “The Holocaust destroyed my family. I know how much the property meant to my mother. How brave she was to reclaim it after the war.”

She returns to the original question. “How could I not?”