News:

Could 16th century palace be hiding 28-tonnes of Nazi gold? SS diary reveals palace is one of five secret locations where Germans stashed WWII treasures

By Stuart Dowell

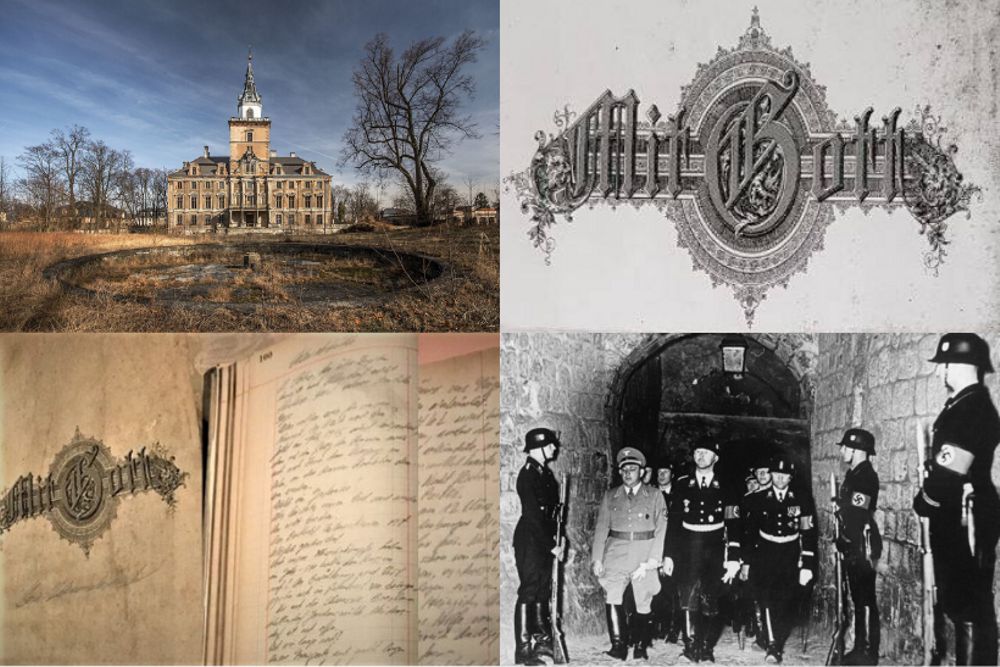

According to the SS officer’s diary, the gold worth billions of euros is at the bottom of a disused well in the grounds of the Hochberg Palace in Roztoka, near Wałbrzych.

The location of 28 tonnes of Nazi-era gold hidden by the Waffen SS in the dying days of World War Two has been pinpointed to an aristocratic palace in Lower Silesia.

The gold worth billions of euros as well as other valuables are said to be 60 metres underground at the bottom of a disused well in the grounds of the Hochberg Palace in Roztoka, near Wałbrzych.

The sensational claim comes from a war diary, written seventy five years ago by a Waffen SS officer under the pseudonym Michaelis, which describes the operation to hide treasure controlled by SS chief Heinrich Himmler at the end of World War Two.

The diary gives details of eleven locations across Lower Silesia and Opole where valuables including including gold, religious artefacts and bank deposits, as well as art from Germany, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia are said to be located.

The diary reveals that the location in Roztoka holds gold deposits of the Reichsbank in Breslau, now the Polish city of Wrocław, and valuables belonging to civilians.

The diary reveals that the location in Roztoka holds gold deposits of the Reichsbank in Breslau, now the Polish city of Wrocław, and valuables belonging to private people in Lower Silesia deposited with the Waffen SS for safekeeping as the Red Army approached in 1945.

Other locations described in the diary are said to hold religious artefacts collected by Himmler’s Ahnenerbe organisation, items connected to SS special projects, and stolen art from across Europe, possibly including Poland’s lost Portrait of a Young Man by Raphael.

The existence of the war diary came to light in March last year when a foundation in Opole named Silesian Bridge announced that it had received the diary from its partners in Germany. The Germans wanted to gift the diary to the Polish nation as an apology for World War Two.

The foundation said its partners are a Christian lodge in Quedlinburg, a small town in Saxony-Anhalt, the members of which are the descendants of Waffen SS officers who were also members of Germany’s pre-war aristocratic elite.

The diary also gives details of eleven locations across Lower Silesia and Opole where valuables including including gold, religious artefacts and bank deposits, as well as art from Germany, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia are said to be located.

Yesterday, Roman Furmaniak, who heads the foundation, revealed to TFN the location in Roztoka of the first of the eleven hiding places detailed in the diary.

Among the documents handed over to the foundation is a map. “Based on instructions I received from the Quedlinburgers, I believe I have located the well in the grounds of the palace,” Furmaniak told TFN.

He said that in 1945, a witness had heard three explosions as the SS backfilled the well shaft. He added that documents that he has seen from the Quedlinburg group suggest that the SS killed witnesses and that it is likely that their corpses are also at the bottom of the well.

The palace in Roztoka is the family seat of the famous Hochberg family, owners of numerous estates in the area. They appeared in Silesia in the early 13th century. One of their estates was Książ castle, which was built by the Piast Duke of Świdnica-Jawor Bolko I Surowy in the thirteenth century.

The diary was handed over by the Masonic lodge in Quedlinburg, a small town in Saxony-Anhalt, the members of which are the descendants of Waffen SS officers who were also members of Germany’s pre-war aristocratic elite.

In 2017, the crumbling pile was bought by a family from Szczecin, which plan to carry out a refurbishment and make part of it available to visitors.

As part of the permits needed to carry out refurbishment work on the protected building, the heritage conservator has also given permission for a search for the well.

Furmaniak says that the owners are keen for the search to begin. As a precaution, they have installed perimeter surveillance as interest in the site is expected to explode among tourists and treasure hunters.

The Hochberg Palace is already known in connection with World War Two treasure as it was listed as a hiding place on the famous Grundmann List.

The story of the lodge goes back to the time of the first German king Henry the Fowler in the early 10th century.

Gunther Grundmann was the heritage conservator for the Germans in Lower Silesia before and during the war.

In 1942, fearful of Allied air raids, he was given the task of cataloguing the vast art holdings of Reich museums, institutions and also private collections.

By mid-1944, he had hidden the items on his list in around 74 places in Lower Silesia. The list came to light in Poland after the war and all the places were systematically checked by Polish and Soviet authorities.

However, during the chaotic end of the war, he was given a new task by Himmler – to hide all the treasures under the control of the Waffen SS.

SS chief Heinrich Himmler, pictured in 1938 at the grave of King Henry the Fowler, believed he was the reincarnation of the king.

Himmler and the Waffen SS had a dilemma. From German spies, they knew of the deal the Allies had struck with Stalin at Yalta, which gave Lower Silesia to a Soviet-controlled Poland. They therefore knew they had to remove all valuables from the region.

Their problems were compounded by the fact that after the Allied landings in Normandy, the Swiss banks started to protect their own interests and broke the deal they had with the Germans to accept their deposits.

The treasure held by the SS included art and valuables that belonged to German institutions and private collectors but also stolen art, and what was called dirty gold, which came from teeth harvested from the jaws of the millions gassed in German death camps.

Grundmann was given the task of hiding all of it. A key accomplice in the project was the war diary author, an SS standartenführer whose pseudonym has been given as Michaelis.

Nazi ceremonies in Quedlinburg.

SS monster General Hans Kammler was a member of the Quedlinburg group and led work on the design of gas chambers and crematoria used in death camps. He was also responsible for the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto after the crushing of the Ghetto Uprising.

In 1945, he was in charge of the all the trucks and transport available to the Waffen SS in Lower Silesia. Aristocratic families who had lived in the region for hundreds of years were desperate to flee with their valuables to areas of Germany that were coming under the control of the Western allies and far from the Soviets, who were seen as savages.

Michaelis decided who could receive trucks and whether they could leave with their possessions. He was the perfect person to protect all the valuable that were under the jurisdiction of the SS.

Along with many other Waffen SS officers, he was a member of the Quedlinburg lodge.

The story of the Christian lodge goes back to the Holy Roman Empire to the time of the first German king Henry the Fowler in the early 10th century. SS chief Heinrich Himmler was fascinated by the old king and believed that he was in fact his reincarnation.

The palace in Roztoka is the family seat of the famous Hochberg family, owners of numerous estates in the area. They appeared in Silesia in the early 13th century.

The Quedlinburgers saw their role as the Christianisation of Germany and Europe. Details about the lodge are hard to come by, but Furmaniak claims that it has an unbroken yet secretive history that goes back 1100 years.

In the 1930s, it formed an uncomfortable alliance with Hitler under which they became part of the cultural elite in the Third Reich. The deal protected its own status and gave Hitler’s thuggish brown-shirt movement an air respectability and also provided the Nazi project a sense of historical legitimacy.

Quedlinburgers could be found in top positions in many Nazi-era institutions, most notably the fearsome Waffen SS. Many were close to Hitler.

No doubt some Quedlinburgers were involved in terrible war crimes. Roman Furmaniak claims, however, that most of the attempts on Hitler’s life came from members of the secretive group.

At the end of the war, many fled to Argentina, Chile and the US. However, some stayed in Germany to continue to fight.

Poland’s Ministry of Culture and National Heritage said it was waiting to have the diary and its contents verified before doing anything.

Fanatical officers of the Waffen SS planned to continue fighting the war. While the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe capitulated to the Allies on VE Day, the Waffen SS did not and it needed the money to carry on fighting.

Furmaniak says that the inheritors of the war diary, the children and grandchildren of these Waffen SS officers, want to pass the diary and other documents to the Polish authorities as an act an good will, as a catalyst for change.

He says that the descendants of the war-time officers want the gift to be part of the world’s heritage. They want any items found to be returned to their rightful owners, but that they want nothing for themselves.

They have seen how the burden of the past and the secrets that followed levied a heavy psychological toll on them.

The children saw the damage that the burden of the war made on their families and they do not want to die under the cloud of Nazism. They want to be free of the baggage of Nazism and the evil that Germans are capable of, Furmaniak says.

Furmaniak told TFN that among the documents handed over to the foundation is a map, and said: “Based on instructions I received from the Quedlinburgers, I believe I have located the well in the grounds of the palace.”

They see the war diary and other documents as a catalyst to leave past traumas behind. They want it to be something that unites Poles and Germans.

“I have heard them say many times that if the diary divides us and does not unite us, they will wait until society is ready,” he said.

The foundation claims that the authenticity of the diary has been confirmed by three of Germany’s leading institutions in this field. This, though, is limited to confirming that the diary itself and the pencil script of the author date from the time of the Second World War and makes no comment on the truthfulness of the diary’s content.

Furmaniak says that part of the diary and other documents have been made available to the Polish authorities.

A guarded comment by Magdalena Tomaszewska from the Information Centre of the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage only went as far as saying that the ministry could not yet confirm the diary’s authenticity.