News:

Was This Picasso Lost Because of the Nazis? Heirs and Bavaria Disagree.

By Catherine Hickley

Officials have refused to refer a dispute over the work held by the state painting collections to a national commission created to review claims of art lost in the Nazi era.

Bavaria has drawn criticism for refusing to refer a dispute over Picasso’s portrait of Madame Soler to a national tribunal that reviews claims of art lost in the Nazi era.Credit...

BERLIN — Almost two decades ago, Germany established a national commission to address disputes over art looted or sold in the Nazi era. While the opinions of the advisory commission are not binding, its recommendations have been routinely followed and about 20 artworks have been returned to the heirs of people who suffered because of the Third Reich.

But now the Bavarian State Painting Collections, which is owned by the state of Bavaria, has refused to refer the case of a Picasso to the commission, a break from tradition that has drawn scrutiny from the federal government and an admonishment from the chairman of the advisory commission itself.

“It is simply inexplicable that the state should refuse to use a mediation mechanism it established itself,” said Hans-Jürgen Papier, the commission’s chairman and a former president of Germany’s constitutional court.

Critics of the decision say that, whatever the merits of a particular claim, the 16 German states should respect the authority of the panel they set up with the federal government in 2003 after Germany endorsed the Washington Principles, a 1998 international agreement calling for “just and fair” responses to claims that arise from conduct in the Nazi era.

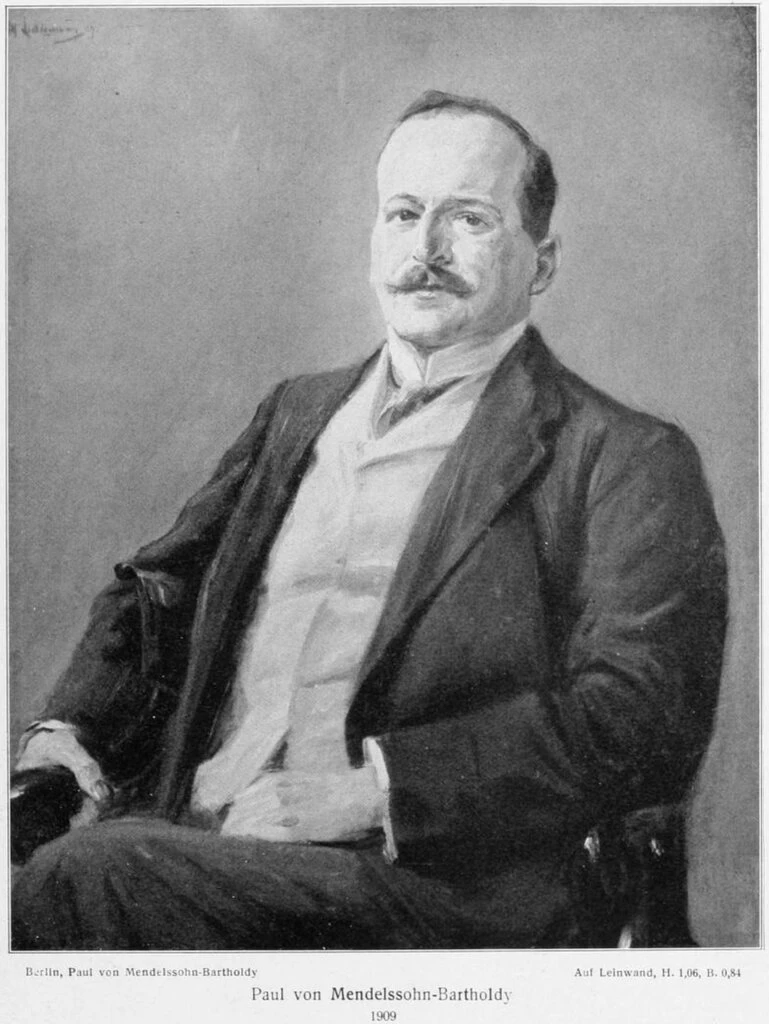

“Regardless of the individual case, agreement to go to the commission should be a matter of course,” said Ulf Bischof, the Berlin-based lawyer for the heirs of Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, a Jewish banker who once owned the Picasso. “The historical context and the demands of fairness and respect require that much.”

Paul von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy in a portrait by Max Liebermann.

Officials of the Bavarian collections have made restitution for 20 artworks in total — the most recent on May 31 — often acting on the basis of their own provenance research, without any need for the commission to step in. In three cases, where there was disagreement, they did agree to have the advisory commission get involved. But in this instance they have said that the painting, “Portrait of Madame Soler,” dated 1903, was not sold as a result of Nazi persecution, a position the heirs are contesting.

The painting depicts the wife of a tailor who befriended Picasso in Barcelona and supported the artist through troubled times with commissions in return for clothing and cash. It is one of five Picasso works the Mendelssohn-Bartholdy family sold to the Berlin art dealer Justin K. Thannhauser in 1934 and 1935.

The Bavarian State Painting Collections bought the painting from Thannhauser in 1964. That institution and the government of Bavaria say that, in their view, the family did not sell “Portrait of Madame Soler” as a result of Nazi persecution and the case is closed.

The heirs argue that Mendelssohn-Bartholdy sold the work under duress. They also say the current holder of a contested work should not be the sole judge of a claim, and they want the matter examined by the advisory commission, established expressly to mediate such disputes.

Though the commission is viewed as the national tribunal for such matters, it can only be called in to mediate if both parties agree.

German Culture Minister Monika Grütters has said she expects all German museums to refer cases to the panel if the heirs request it, according to a December 2016 letter she sent the Mendelssohn-Bartholdy heirs. Her ministry reiterated that position in an email recently.

But the ministry noted that, under Germany’s federal structure, the decision lies with the states.

Bavaria had once previously refused to refer a case to the commission. It was a case involving six works by Max Beckmann that were claimed by the heirs of the art dealer Alfred Flechtheim. That dispute, however, arose in 2013, before the culture minister had made clear her expectation that all state-funded museums submit cases to the commission.

“I have absolutely no understanding for the fact that some publicly financed institutions refuse to refer cases to the advisory commission,” Grütters told a 2018 conference to mark the 20th anniversary of the Washington Principles.

Papier, the commission’s chairman, dismissed Bavaria’s view that the claim is unjustified as “irrelevant,” saying it is up to the commission to evaluate such cases, not the holder of a disputed artwork. Bavaria’s resistance to referring the case to the panel “must leave the impression that there is no will or appropriate means to address historical injustices in Germany,” he said in an email.