News:

Revealed: Immigration Documents Filled Out by Austrian Jews During the Nazi Occupation

By Dr. Yochai Ben-Ghedalia

A trove of documents from Vienna’s Jewish community during the Anschluss period has been revealed to the public for the first time thanks to a collaboration between MyHeritage and the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People at the National Library of Israel. The collection contains 228,250 records, including scanned original documents submitted by Jews hoping to emigrate from Vienna. These documents, available on the Library’s website, provide extraordinary insights into the life of Vienna’s thriving Jewish community in the years 1938–1939

On March 12, 1938, Nazi Germany invaded Austria, an event euphemistically known by the German term “Anschluss”—meaning a territorial annexation.

This was no ordinary invasion, and when Hitler arrived three days later for a triumphal march across the city, hundreds of thousands of Austrians gathered to cheer him along his route. According to various testimonies, there was not a single rose left in Austria that hadn’t been picked for the occasion.

For Austria’s roughly quarter of a million Jews however, it was not a cause for celebration. The abuse against the community’s leaders and rabbis began immediately after the Anschluss with many arrested and sent to the Dachau and Buchenwald concentration camps. The Nazis also closed the community’s offices in Vienna.

Two months later, the offices re-opened, and now contained a new department: “The Vienna Jewish Community Welfare Department – Immigration Office.” Every Jew who wanted to emigrate from Vienna—meaning more or less all of the city’s Jews, from the Hasidic to the assimilated, had to fill out forms, in duplicate, which were submitted to the office.

The Vienna Jewish community archive is one of the largest and most important community archives in the CAHJP. The collection, which dates back to the 17th century, from the period before the expulsion of Vienna’s Jews, was sent to Jerusalem by the community in Vienna after the Holocaust. The immigration forms are part of this important archive.

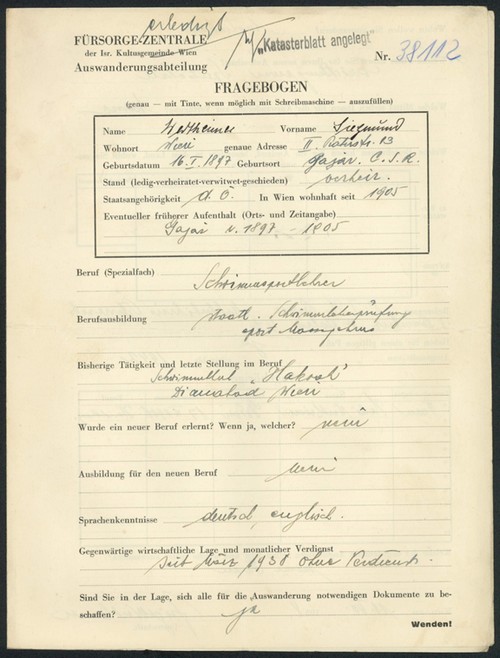

The forms included the applicant’s first and last name, his or her exact address, date of birth, place of birth, personal status (married, single, etc.), personal information, citizenship, the date from when the applicant had resided in Vienna, where the applicant resided before arriving in Vienna; the applicant’s profession, occupational history, languages, financial situation and monthly income, as well as information regarding the desired immigration destination. The information regarding the immigration destination included the names of relatives and friends abroad (as well as their address and degree of kinship), and passport and immigrant visa information. The questionnaires included information not only about the applicant, but also about the applicant’s household members, mainly their spouse and children, but often also parents or in-laws.

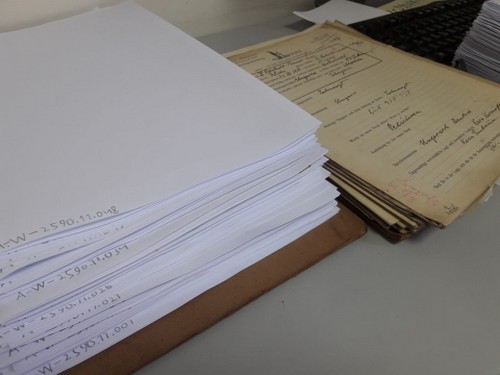

The forms were submitted in duplicate with additional attachments inserted at various stages in the immigration process. Each form was assigned a serial number. At first, the forms were arranged only by serial number, but later, the immigration department separated the duplicate copies, keeping the numerical system for one, and arranging the other (incomplete) alphabetically by German surname. The immigration department maintained three indexes for the forms: numerical, alphabetical and one by profession, which was extremely pertinent for immigration applications. As early as 1938–1940, the community’s research department and international Jewish aid organizations such as HIAS prepared reports based on the important data gathered from the forms to optimize the emigration process.

However, in those first years of the Nazi occupation, the community was not working in a vacuum. The Gestapo was supervising its operation, with this effort led by Adolf Eichmann. In this first stage, as Eichmann had been tasked with emptying Vienna of its Jews through emigration, the Jews and the Nazis shared a common interest. In the later stages, when emigration was no longer allowed, the Gestapo used the information from the transmigration forms to optimize its euphemistically termed policy of “relocation to the East” of Vienna’s Jews, effectively sending them to concentration and extermination camps.

The two sets of immigration files kept by the Vienna Jewish community’s immigration office arrived in Jerusalem along with the rest of the community archives. Both sets have been preserved in their original order: the set according to serial number from 1-400, 401-800, etc. and the alphabetical set according to last name. Given this system, it was not possible to know whether a certain individual’s form was included in the alphabetical set without physically going to the archive and inspecting the relevant folder’s contents. Similarly, the numerical set was not easily searchable because it was impossible to guess the serial number of a particular individual.

To extract the information hidden in this historically important trove of documents, the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People and the National Library teamed up with MyHeritage. As a leading commercial genealogy company, MyHeritage understood the value contained in these forms. Beyond comprehensive documentation of Vienna Jewry, one of the largest Jewish communities in the Jewish world on the eve of the Holocaust, the collection could also provide information about relatives living on other continents, a missing link that was not readily available in the databases generally used for researching family roots.

As part of the project, the Central Archives team separated the contents of the binders into the individual forms, which were then sent to the National Library of Israel’s state of the art digitization center for scanning. The scans were linked to entries in the archive’s catalog, which at this stage contained no information and were still inaccessible to the public. A digital copy of the hundreds of thousands of scanned pages was also sent to MyHeritage, which engaged a large international team that set to work developing a detailed key of the main data points contained in the forms. The result was a huge Excel file, with over three hundred thousand lines, spanning 129 columns. A copy was sent to the CAHJP, and the data was simultaneously processed and uploaded to MyHeritage’s systems.

The archive team processed the millions of data points into catalog records adapted to the archive’s own data structure. Great effort was invested in unifying various terms, such as the hundreds of different ways personal status or the nature of the kinship of family members and relatives abroad was recorded. We also had to correct quite a few errors, many of which were made on the original forms. We all make mistakes when we have to fill out endless forms like this. We enter our place of birth instead of our address, switch a date of birth with the date on which we are filling out the form, and we might even get confused about the century we were born in. For example, in 1938, some people wrote that they were born in 1988, when of course they meant 1888. It is easy for people in a terribly stressful situation to make mistakes like these, even more if you were an immigrant from regions of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire (Galicia, Bohemia, Moravia, Bukovina, Hungary, etc.) and didn’t have a very good command of German. A great deal of work has taken place and the effort is still ongoing to unify and standardize the names of the applicants’ birthplaces and of places where their relatives lived. It is fascinating to see how Galician Jews in Vienna imagined the geography of the United States, and the dozens of different ways New York and its boroughs were written on the immigration applications.

After resolving the various data errors, we created coherent information from the fragments of details, according to computer algorithms, to produce the following sequences: applicant: last name, first name, date of birth (day/month/year), place of birth (geographical place) and personal status. We created other sequences for the family members listed on the application and for relatives listed as living abroad.

Sometimes the original form is missing, and a note was inserted indicating that the form had been removed for various administrative purposes and not been returned. In cases where these notes included useful information, such as the applicant’s name and the form’s serial number, we left the information to indicate that there was once a form here, even if it is not extant today.

The catalog information was uploaded to the (initially) hidden catalog entries created at the early stages of the project, and these were then made accessible to the public, along with the scans.

The collection is accessible on the Library and CAHJP’s website and it is accessible to MyHeritage users as well. The MyHeritage platform is also able to compare the information with that contained in other databases available on their website, yielding further insights from various sources about the individuals mentioned in the records.

In the weeks since the collection went online, many have managed to learn more about their family history and fill in unknown details. If your family resided in Vienna on the eve of World War II, there is a good chance that they also filled out a form, and you can find it on the National Library of Israel website, or at the following link.

If you are experiencing difficulty with the site, please contact us at cahjp@nli.org.il

Vienna Jewish Community Welfare Department- Immigration Bureau form, filled out by Siegmund (Zsigo) Wertheimer on August 11, 1938. Zsigo Wertheimer was a well-respected professional women’s swimming coach. He was married to swimmer Hedi (Hedwig) Bienenfeld who excelled at the breast and backstroke and who became famous in 1924 for winning first place in an “Across Vienna” open-water swim competition

This one-of-a-kind source contains more than personal information and family stories. From it, one can learn not only about those terrible days, but also about the richness of Jewish life in Vienna between the two world wars. You can discover the exact addresses of writers, playwrights, musicians, Rebbes and Torah scholars, or map out the streets and neighborhoods where Jews lived or the places from which they immigrated to Vienna, their occupations and the many languages they spoke.

But above all, the collection tells the story of how the Jews of Vienna woke up one morning to find themselves under Nazi rule. It tells of their desperate attempts to secure the sums that would enable them to leave and the bureaucratic nightmare of validating passports, obtaining an immigration visa as well as a “transit” permit to an intermediate country.

In her novel Transit, Anna Seghers, herself a Jewish refugee who attempted to leave Europe, tells a joke that circulated among the refugee community trying to emigrate via the port of Marseille, which was under the control of the French Vichy government:

A person gets to heaven and arrives in a waiting room where there are two doors, one to heaven and one to hell. For half a year, he is shuffled from one clerk to another in an endless pursuit of forms and signatures. At some point he turns to the clerk in charge and tells him that he can’t deal any longer with all this waiting. He is giving up his chance to go to heaven and prefers instead to be sent to Hell. ‘I’m sorry for having to tell you this,’ says the clerk, ‘but you are in Hell.’