News:

Were These Artworks Looted? After Seizures and Lawsuits, Some Still Debate

By William D. Cohan

Several museums and collectors have surrendered artworks by Egon Schiele to investigators who say they were looted. But others are asserting that the evidence is inconclusive.

“Dead City III,” a painting by Egon Schiele, is the subject of a lawsuit filed by the heirs of a Jewish art collector who say it and other works he owned were looted by the Nazis.

For decades, several important museums and collectors ignored suggestions that the works they owned by the Austrian master Egon Schiele had been stolen by the Nazis from a Viennese cabaret performer, Fritz Grünbaum.

Instead, many embraced an alternative account told by a Swiss gallerist. He said that in 1956, 15 years after Grünbaum’s death in the Dachau concentration camp, he had come into possession of dozens of Grünbaum’s Schieles.

The gallerist, Eberhard Kornfeld, said Grünbaum’s sister-in-law had approached him, looking to sell a bunch of the Schiele artworks. Kornfeld said he bought most of the 81 Grünbaum Schieles from her and put 65 of them up for sale, an event that eventually led to more sales and resales and caused the Grünbaum Schieles to end up in collections around the world.

But a New York civil court ruling several years ago and, more recently, the findings of investigators working for the Manhattan District Attorney have undermined the credibility of Kornfeld ’s account. The New York civil court held that Grünbaum never willingly sold or surrendered any of his works. In recent weeks the New York City prosecutors were able to persuade several museums and collectors to surrender nine Schiele works, valued at more than $10 million, to Grünbaum’s heirs.

Now the heirs, Timothy Reif, David Fraenkel and Milos Vavra, are pursuing legal claims in New York that seek the return of 13 additional works by Schiele held by three museums, the Albertina and the Leopold in Austria, and the Art Institute of Chicago. The heirs argue in court papers that these works, which include a well-known painting, “Dead City III,” held by the Leopold, were also stolen from Grünbaum and were never in the possession of his sister-in-law, Mathilde Lukacs.

Raymond Dowd, the heir’s lawyer, wrote in a federal suit filed in December against the two Austrian museums that the Lukacs story has long been derided by Holocaust scholars “as implausible because Lukacs was herself imprisoned in Belgium during World War II after escaping Vienna.”

Kornfeld’s account was first publicly aired in 1998 when “Dead City III,” a moody 1911 portrait of the Czech town of Cesky Krumlov where Schiele lived in 1910, was briefly seized as looted in New York by then Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau. The work was ultimately returned to the Leopold museum in Austria. #

#

Grünbaum was taken away by the Nazis, but some holders of art work he once owned do not agree that his collection was also confiscated.

William Charron, the lawyer who represents the Leopold Museum, declined to be interviewed. But in its court filings, the museum has argued that the plaintiffs are too late in making their claim and that the federal court in Manhattan where the heirs filed their lawsuits does not have jurisdiction.

The museum said in its legal filing that it is also relying on a federal court decision in which the judge ruled against the Grünbaum heirs in a dispute over another Schiele. That judge found that the lawsuit was also filed too late and that documents provided by Kornfeld supported his account of having bought the works from the sister-in-law, Lukacs. (The heirs have challenged the authenticity of those documents, which include a receipt said to have been signed by Lukacs.)

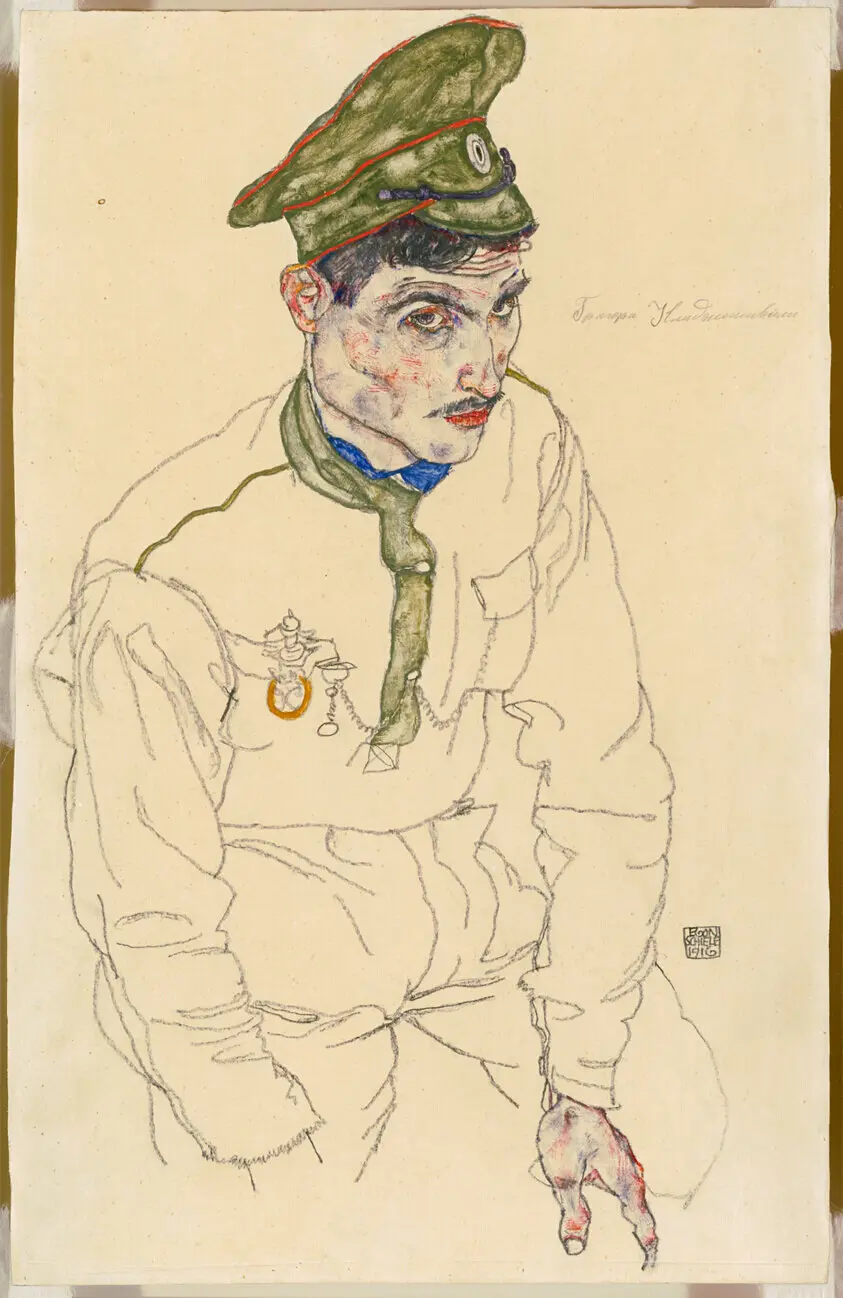

The Art Institute of Chicago, which holds the Schiele drawing “Russian Prisoner of War,” and is being sued separately by the Grünbaum heirs, has also argued that the claim is time-barred and that the earlier federal case decided that the Nazis had never seized the collection. The drawing in Chicago is also the subject of a seizure order by the Manhattan district attorney’s office, which the museum is contesting. The Art Institute has countersued the Grünbaum heirs for “a declaration of title” to the artwork.

Spokesmen for the Leopold and Albertina museums, which are owned by the government of Austria, declined to comment, citing the pending litigation. A spokesman for the Art Institute wrote in an email, “We are confident in our legal acquisition and lawful possession of this work.”

So far, Reif, a judge on the U.S. Court of International Trade, and Fraenkel, a former commercial banker, have secured the return of more than a dozen Schieles they argue were taken from Grünbaum. (Vavra is retired and lives in the Czech Republic.)

The return of seven Schieles was announced in late September by Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan District Attorney, whose office convinced three museums and two collectors to surrender the works. The Museum of Modern Art and the Morgan Library in New York were among the group that returned works, as was the art collector and former U.S. ambassador to Austria, Ronald Lauder. He gave back a watercolor, “I Love Antithesis,” a self-portrait of the artist created in 1912.

In an interview, Reif said the seven Schieles will be sold by Christie’s, in two sales this month, with the proceeds going to the Grünbaum Fischer Foundation, which supports underrepresented artists.

More recently, three additional institutions, the Carnegie Museums, in Pittsburgh; the Allen Memorial Art Museum, at Oberlin College; and the Vally Sabarsky Trust in New York have agreed to surrender Schiele artworks formerly owned by Grünbaum.

Grünbaum assembled his collection of Schieles after the artist’s death in 1918 from the Spanish flu. The New York investigators have agreed with the plaintiffs that Grünbaum’s wife was forced to turn over his art collection to Nazi officials when her husband was imprisoned in 1938. Investigators say there is evidence that the Nazis, who viewed Schiele’s work as degenerate and thus disposable, put it in a warehouse in Austria. The investigators have not addressed specifically how they believe Kornfeld obtained the Schieles, if not from Lukacs. But in a press statement they pointed to a longstanding business relationship Kornfeld had with the son of the art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt, whom the Nazis assigned the task of selling off degenerate art.

Kornfeld, however, has said that, instead of being diffused in multiple sales, that most of the Grünbaum Schieles were maintained as a collection, one ultimately held by Grünbaum ’s sister-in-law who was herself persecuted by the Nazis and fled Vienna for Brussels in 1941. By Kornfeld’s account, the Schiele works escaped with her.

At Kornfeld’s sale in 1956, Otto Kallir, a Viennese Jewish art dealer who had helped Grünbaum buy some of the Schieles decades before, bought 18 of them, including “Dead City III.” Kallir, who fled Vienna, opened a gallery on West 57th Street in New York, Galerie St. Etienne, and later swapped “Dead City III” and three other Schiele artworks with Rudolf Leopold, a Viennese ophthalmologist who had one of the world’s best Schiele collections. Kallir received six Schiele watercolors and two drawings, plus a Gustav Klimt portrait in the exchange. Leopold later sold his vast art collection to the Austrian government, which built the Leopold Museum in Vienna.

“Russian Prisoner of War” by Schiele, another work being sought by Grünbaum heirs. The dispute focuses on the credibility of a Swiss gallerist who says he bought the Schiele works from Grünbaum’s sister-in-law.

Kallir also bought the “Russian Prisoner of War” drawing at Kornfeld’s 1956 sale and it eventually ended up in the collection of the Art Institute.

In the ongoing cases, Dowd, and his clients, Reif, Fraenkel and Vavra, are again challenging the credibility of Kornfeld’s account. Their arguments were embraced by the judge in a case they filed in 2015 in New York State Supreme Court against Richard Nagy, a London art dealer who was trying to sell two other Grünbaum Schieles, also bought from Kornfeld in 1956.

The judge in the case, Charles Ramos, found for the heirs, writing in his decision: “A signature at gunpoint cannot lead to a valid conveyance.” That ruling was upheld on appeal in 2019, when the appellate court said, among other things, that it had not found credible documentary evidence that “the artworks were purchased by Kornfeld from Mathilde. Moreover, even if Mathilde had possession of Grünbaum ’s art collection, possession is not equivalent to legal title.”

There are those such as Otto Kallir’s granddaughter, Jane Kallir, who continue to believe Kornfeld’s account. She runs the Kallir Research Institute, an art historical research organization, and before that her grandfather’s gallery, and has testified in court that she does not believe “Dead City III” was stolen from Grünbaum. She declined to be interviewed, citing the pending litigation in Austria. But in a 2007 deposition in another case, she said she regarded Kornfeld’s account of his purchase of works from Lukacs as credible.

The Grünbaum heirs face an uphill legal battle in the case against Austria because of the difficulties of suing a sovereign nation in U.S. courts. Typically, the courts have not allowed lawsuits against sovereign nations except in instances where there has been a viable claim that international law was violated or where nations had waived their sovereign immunity.

The Grünbaum heirs have asserted that there has been such a waiver, but Austria and its museums deny that. The case involving Austria is on a delayed schedule because of the intricacies of lawsuits involving sovereign nations, but the Art Institute case has moved forward in recent weeks as the parties debate whether the district attorney’s office, because of its seizure order, should now be a party to the suit.