News:

A German museum puts the questionable provenance of its art on display

By J.T.J. Friedrichshafen

BETWEEN 1933 and 1945, in a systematic effort, Germany’s Nazi party stole or forced compulsory purchase of a vast number of artworks, both from museums around Europe and from Jewish collectors. The exact figures are impossible to know, but estimates suggest the number of looted paintings alone totalled 650,000—a fifth of all paintings in Europe at the time.

Restitution efforts for private claims in particular have been slow, and it wasn’t until 1998 that an international set of principles to deal with the problem of Nazi-looted art was created. Forty-four countries came together to establish the Washington Principles, which encourage public collections to undertake provenance research, and if necessary, return stolen artworks in their possession to the rightful owners or their descendants, particularly in the case of Jewish collectors who were forced to flee. Time is of the essence: these processes become more and more difficult as trails grow colder and original owners (and their memories) grow older.

The Nazi regime labelled many works, especially avant-garde and modernist ones, as Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art)—“un-German”, “communist”, or otherwise anathema to Nazis values. Exhibited in an infamous show of the same name in 1937, such works were purged from art collections, and either destroyed, or, in many more cases, sold to provide cash for the war effort. As more and more Jews fled or were murdered, their art collections were bought for a pittance, or simply plundered. Hermann Göring, in charge of this effort on Hitler’s behalf, also made himself a fortune on the side.

While restitution efforts began in 1957, many of those involved in dealing in looted art both before and after the war did not realise that the artworks had been stolen. In some cases, that ignorance was wilful—the result of a temptation to look away from a painful and costly truth—but in others, it was the product of simple negligence.

But over time, German attitudes have changed: the willingness to face up to the past and make it right is today a national value with broad public support. This has been particularly clear following the discovery of Cornelius Gurlitt’s cache of art in Munich in 2012, which earlier this year finally made its way into dedicated shows in Bern and Bonn, following numerous legal entanglements. Both exhibitions will head to Berlin’s Martin-Gropius Bau later this year. Germany’s reparations effort includes a public fund of almost €6m ($7m) per year dedicated for museums’ provenance research via the German Lost Art Foundation.

It was from this fund that the Zeppelin Museum in Friedrichshafen drew to begin a project of sifting through its own collection of almost 4,000 artworks, including an impressive selection of paintings by “degenerate” Otto Dix, as well as many Baroque and Gothic pieces. Because Friedrichshafen was a hub for industrial weapons production, the museum had its previous art collection wiped out by bombing during the war. As a result, its entire collection was purchased after 1945. This didn’t mean their artworks were necessarily “clean”. Multiple dealers, such as Benno Griebert and Otto Staebler, who had long-term relationships with the museum after the war, have been shown to have connections with Nazi-looted art.

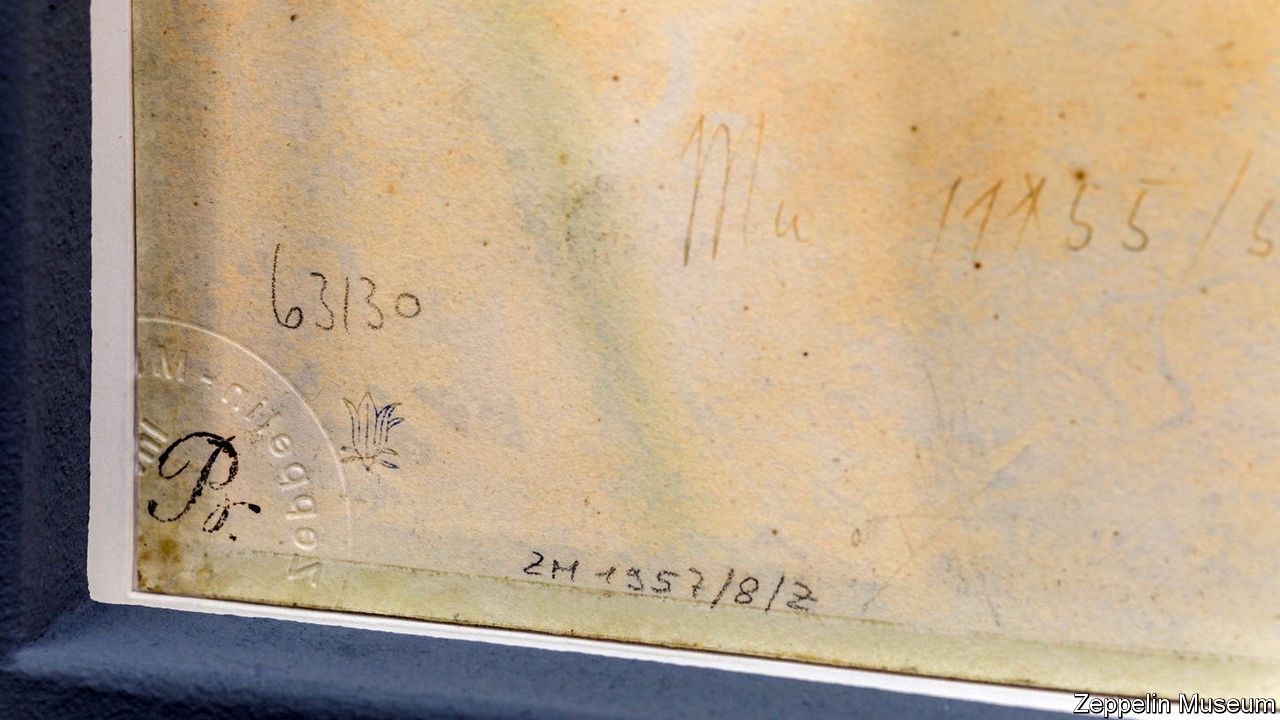

“We want to show our visitors how we work,” Fanny Stoye, the provenance researcher on the project, explained. The current exhibition, “The Obligation of Ownership: An Art Collection Under Scrutiny”, allows its audience to answer questions about the key periods of ownership, most notably: where was the artwork between 1933 and 1945? The setup is significant: paintings and sculptures are exhibited with their versos exposed, so that identifying marks and numbers are revealed. “It’s better to do your research, and then it’s you who takes action,” Claudia Emmert, the museum’s director, explained.

The exhibition’s transparent, systematic research is made clear to even the casual observer with a “looting danger” classification system of green, yellow, orange and red stickers on the artwork’s card. Around half the labels are green, and almost as many are yellow. Only two have been assigned the more precarious orange, and none are labelled red. But there are many gaps in their investigation. “I’ve been working on this since August 2016, but I still have to do more research,” Ms Stoye said. “There is no clean market…yet.”

Even so, the show has made a crucial difference to the wider field of provenance research. One of the pieces on show here with the “orange” designation has added a new character to the list of Jewish collectors whose works may have been plundered by the Nazis: Max Strauss, proven to be the owner of Otto Dix’s “Bouquet”, which the Zeppelin Museum has in its collection. The painting’s whereabouts are entirely unknown between 1928 and 1990, at which point it turned up, mysteriously, as so many others have done: in a bonded warehouse somewhere in Switzerland.

Strauss, who emigrated to America and never returned to Germany after fleeing for France in 1933, is long-dead; his family had no idea about his art collection in Berlin. Did he sell this, and other works, in Berlin before he left Germany? And if so, was it under duress? The final section of the exhibition is entitled “An Ongoing Obligation for Museums”. With the current store of knowledge as it stands, it is to be hoped that more institutions, and indeed, private collectors, follow the Zeppelin’s lead—and do so publicly—to find these answers.